14/11/2025 update: Model names of shuttles used corrected. Thanks to the ISB Man for pointing them out!

Automated people movers (APMs), the transport mode used in the Punggol LRT, have been frequently labelled as “gadgetbahns”, a term used to describe transport modes incapable of scaling to meet the needs of big-city mass transportation, and often coming with a whole host of other issues relating to proprietary technology. Yet, for all the flak the APM mode deserves in its Singapore applications, they can still mostly redeem themselves with longer formations producing higher capacity, as seen in examples around Tokyo and Taipei. (We’ve also come up with our own proposal to enhance the capacity of the APMs in the northeast too — see TM50’s Fernvale LRT line, also planned to operate 4-car formations)

This next gadgetbahn that Punggol will receive however, won’t be so fortunate in its redemption arc. Primarily, its fault revolves around an issue discussed earlier this year on the site, particularly in the discourse around the development of autonomous public transport.

The day is 20th September 2025, and I had been invited to the special soft launch of new autonomous shuttles to ply around Punggol and the Punggol Digital District starting next year. Prior to that, media releases indicated that these driverless shuttles would take a similar form to currently-running pilot trials around China, with the technology being imported through joint ventures with local transport operators.

It was a grand event, with loads of senior management staff from LTA and big industry players like ComfortDelgro and Grab present to witness this pivotal moment in our local transport history. This would be the first time autonomous vehicles were made accessible to the wider public, rather than specific geo-fenced demographics in previous limited trials. Albeit with a catch, which we’ll get to later.

As with everything big about transport, our Acting Transport Minister Jeffrey Siow was present, where he delivered a lengthy speech about technological progress and the exciting prospects these driverless shuttles could bring about. Spoilers: these autonomous shuttles could be used for night transportation, filling the gaps left by the exit of traditional public transport in this field. Also mentioned was their potential deployment in Tengah, where URA concept renders from the 2010s have consistently espoused the idea of self-driving pods as “smart transportation” for the new town. He then went on a long litany afterwards about making Singaporeans feel proud about their public transport, a monologue that could be considered borderline inappropriate considering the quarter-long spate of rail disruptions hitting us since July.

His MOT colleague Sun Xueling took the stage next, explaining the specifics of the Punggol trial and appealing to the public to drive courteously around the new autonomous shuttles. Knowing how Singaporean drivers work, LOL.

Anyway, after they had all said their piece, the big moment came. On the push of a button, the curtains concealing the vehicles used on the Punggol AV pilot would drop, revealing what lay in store for Punggol residents. As the countdown began, a wave of cameras began pointing intently towards the curtains, eagerly awaiting their first glimpse of these shiny new paragons of driverless technology. Finally, the moment came, and as the curtains dropped, so did my heart. For those who had numerous questions when they saw car-like vehicles being featured for use on “fixed route driverless shuttles”, I share your doubts.

Now, while I certainly was not expecting any full-sized autonomous bus to appear at the roadshow anymore knowing the products of this industry, there was still a certain expectation of capacity of some sort, given that the very nature of such shuttle services was still going to more closely mirror a fixed-schedule bus, rather than an on-demand taxi or ride-hailing service with dynamic routing. Of the three vehicles unveiled that day, only one remotely met this expectation — the larger vehicle prepared by the Grab-WeRide joint venture, a spinoff of Yutong’s Xiaoyu driverless shuttle commonly used in China. The rest? Unironically, cars that would otherwise be sold in the Cat B COE category elsewhere in Singapore.

Alongside the 7-seater Xiaoyu bus featured were two other driverless variants of off-the-shelf vehicles by familiar car brands. Alongside Grab-WeRide’s 7-seater Xiaoyu featured was the 5-seater Geely Farizon SuperVan, and ComfortDelgro-Pony.ai’s 5-seater Toyota Sienna. These vehicles, classified as multi-person vehicles (MPVs) capable of carrying up to 7 passengers, have been modified to only permit the carriage of four or five passengers, primarily due to the front passenger seat being permanently closed to passengers, as well as the removal of more seats to facilitate passenger movement within the vehicle.

These low-capacity impressions of vehicles meant to emulate the role of public transportation form a stark contrast against the role they’re expected to play, first in the Punggol area and eventually on a nationwide level. On one hand, it is evident of their intended direction of evolution — to someday serve as the technology-fuelled replacement for manned buses requiring a driver to operate today. On the other, the clearly low-capacity nature of these vehicles suggests an inclination towards a service more closely resembling demand-responsive microtransit. The million-dollar question surrounding the Punggol trial is this: will these capacity-impaired shuttles enable the concept of autonomous technology to truly take off in public transportation, or will this be yet another in a long-running streak of failed trials in our public transport history?

More is at stake than just the business prospects of the two consortiums participating in this demonstrator project: LTA and MOT have clearly placed very high hopes upon the Punggol AV trial, with its fate playing a predominant role in determining the trajectory of future autonomous vehicle development across the rest of Singapore. Given the very real concerns in the public transport industry which favour the timely introduction of self-driving technology infused into the system, this trial carries the heavy historical burden of ensuring its vindication. Without it, much of the abundant transit needed to sustain Singapore’s car-lite way of life would fall apart, amidst escalating manpower shortages and rail lines struggling to match capacity to demand. And for the latter, we can’t deliver more of them quickly enough to alleviate existing capacity limitations, much less future ones.

Many ways to fall off a cliff

As much as expectations for Singapore’s first live-road autonomous vehicle trial remain high for the future prospects of the technology, there are many ways that it can go wrong, potentially jeopardising ridership numbers, and the eventual success of the Punggol trial. From the way the shuttles have been set up, some of these fatal factors have been put in by the project’s very creators.

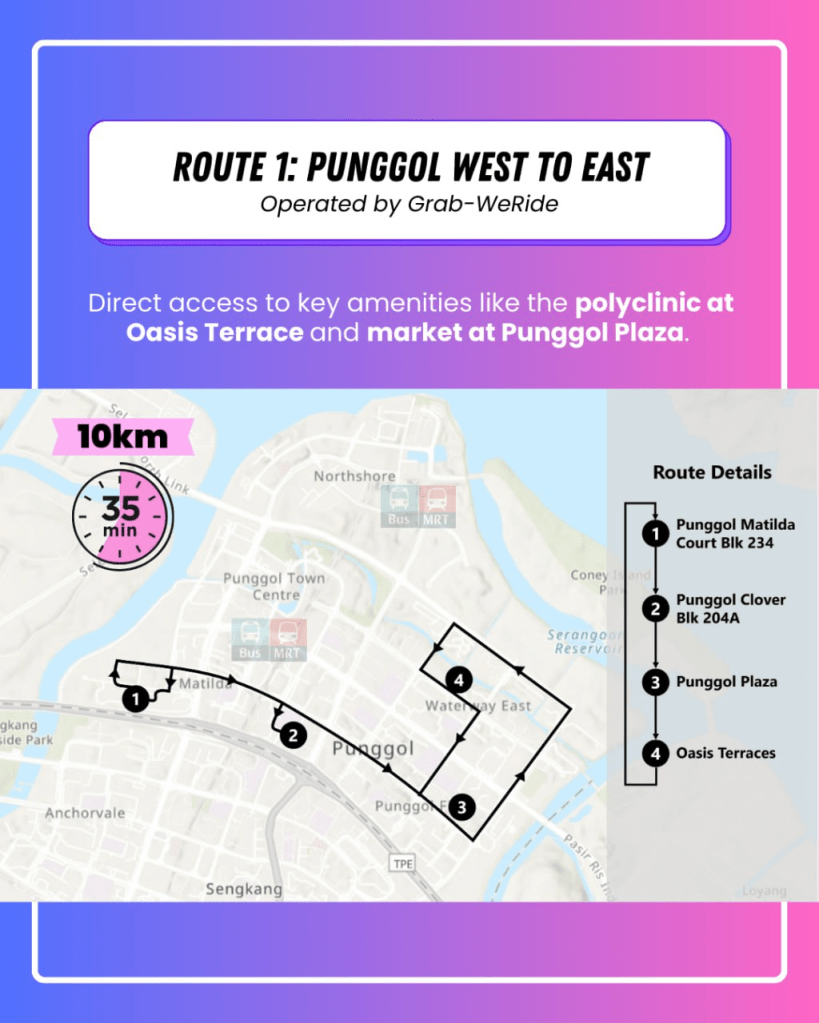

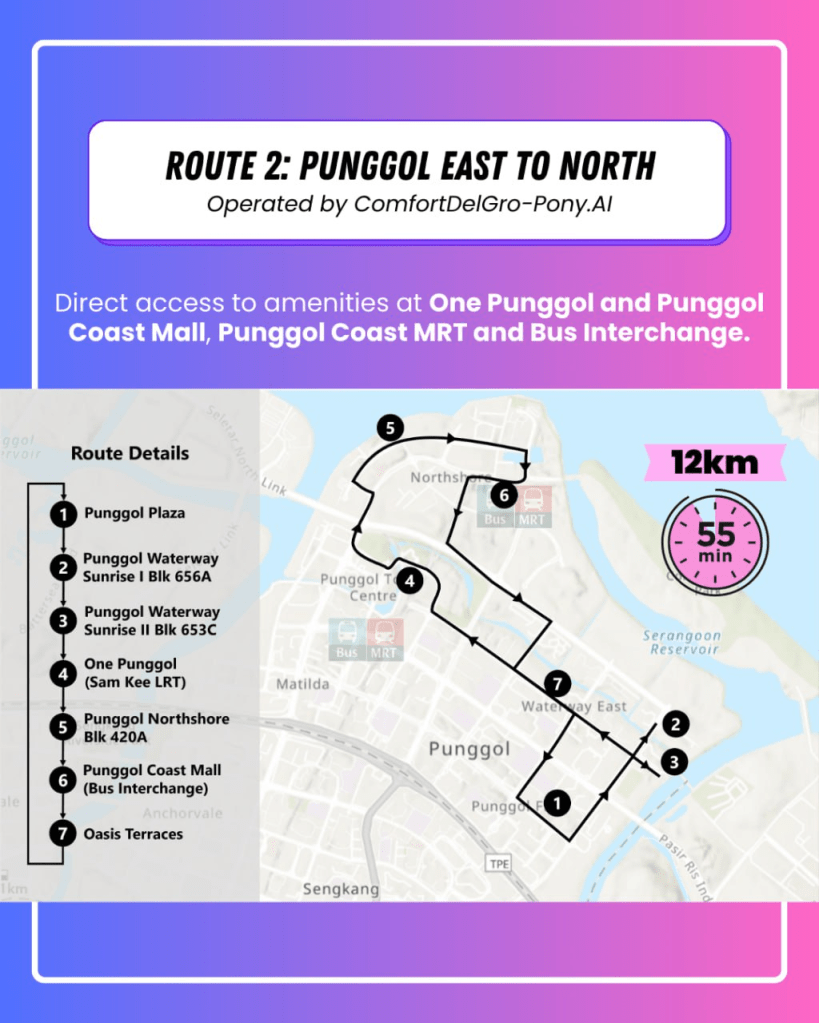

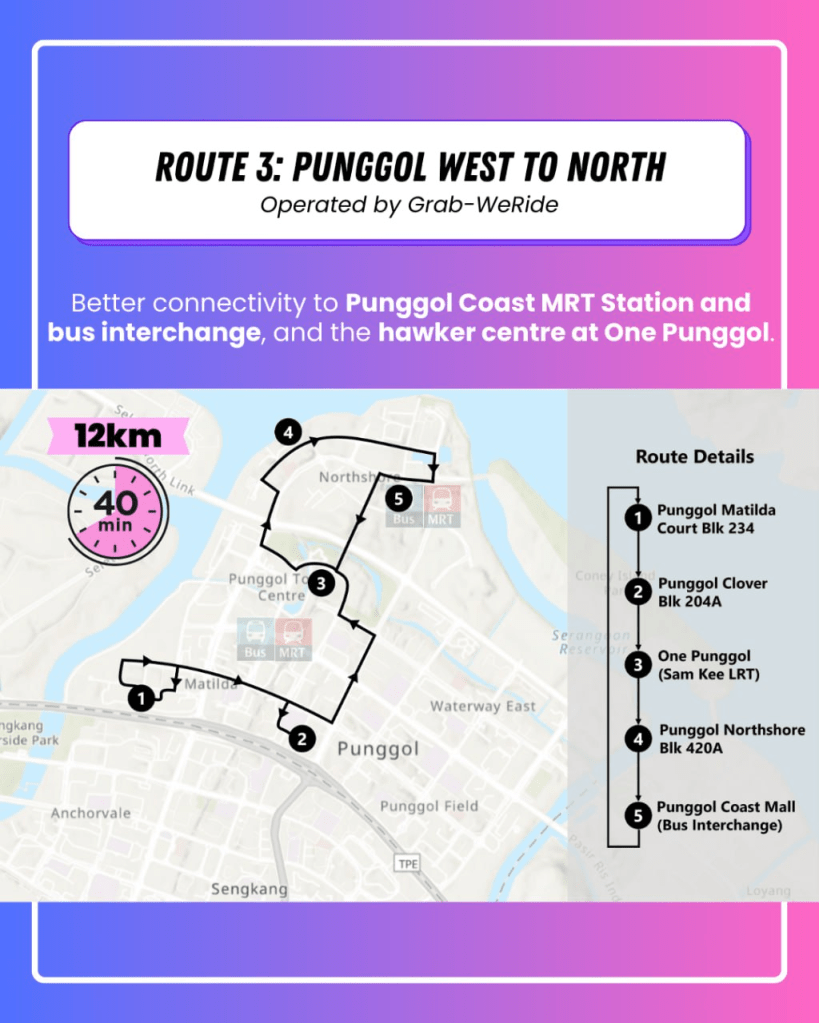

To give a quick introduction of these proposed driverless shuttles for those who were unable to visit the exhibitions around Punggol last month, the general gist of these services is that they operate as circulator services (i.e. without an explicit terminus point, unlike conventional public bus services like Kovan’s 115), more similar to the free shuttle buses offered by neighbourhood shopping malls linking them to adjacent housing estates. These shuttles do not call at every bus stop like public buses do; only a select few precincts are served, linked in a large unidirectional loop. In a weird way, the Punggol driverless shuttles exist for a similar purpose — they’re predominantly designed to connect residents to local retail clusters rather than regional transport nodes or town centers. Their routes give Punggol MRT station (and Waterway Point) a hard miss, instead centered around amenities such as Oasis Terraces and Punggol Coast Mall (and the MRT there, which is a lot further from the residents these shuttles serve).

(Swipe for the other routes these shuttles will ply on!)

Interestingly, these driverless cars cosplaying as shuttle buses won’t be using conventional bus stops, unlike what’s being done for many free shuttle buses that currently exist. Instead, they will take a significant detour to enter the housing estates themselves, going right up to drop-off porches at the foot of HDB blocks. There’s a notable reason for this — none of the vehicles exhibited at the launch event were of the right-hand drive (RHD) configuration needed to operate legally on Singapore roads. Because of the technologies’ Chinese origins, the Singapore partners somehow opted instead to import ready-made prototypes from China wholesale, which also included retaining the left-hand drive (LHD) setup alien to Singapore. As you can probably tell, that means that the shuttles, at least the higher-capacity ones that aim to resemble a minibus more closely, will simply not be able to serve roadside bus stops. Representatives from both Grab and ComfortDelgro indicated that Singapore-compliant RHD vehicles are on the table for future introduction, although when that happens is another question altogether.

Last but certainly not the least detail to miss, these shuttles will be set apart from conventional free shuttle buses by their access — with a fare required being one of these differences, but more crucially, that intending riders must book a ride on these shuttles through the respective operator’s apps, and be allocated to a specific timeslot.

Left behind

As I mentioned earlier this year regarding the trend of the autonomous vehicle industry, the decision to shrink big 12-meter buses to small 7-seater pods is driven by the belief that removing the driver will enable an explosive increase in the number of vehicles operated, thus reducing the individual capacity requirement for each vehicle. Designating literal cars to take on the role of autonomous shuttle “bus” services around Punggol, while not exactly the mainstream approach, follows similar logic. The fact that this line of reasoning is fallacious for the huge capacity reduction it would cause aside, this very strength of autonomous vehicles is simply not being adequately exploited, especially in the critical early stages where results are being demanded to justify further development. With a total of only ten vehicles planned for rollout between the three shuttle routes in Punggol, that works about to about an average of three vehicles per route, and per the official LTA statistics about their travel time, an average frequency of 15 – 25 minutes depending on individual route. Not any better than the conventional buses they’re intended to supplement and eventually replace, which still operate some fairly decent feeder service around Punggol despite the presence of the APM system.

This characteristic of the service initially provided is what lent both consortiums to opt for a reservation system to allocate highly limited seat capacity across potentially overwhelming demand, but it serves to reinforce the point that the low capacity of the selected vehicles render them inappropriate for the purposes of providing connectivity enhancement to a town where bus connectivity is notably scant away from the town center, and where obvious gaps continue to remain due to unique oddities in the road network.

But why does individual vehicle capacity remain relevant, even when the prospect of removing manpower limitations is on the horizon?

With some sort of vehicle resembling a conventional bus, a large family of ten is but a minor inconvenience on board, at most hoarding seats that they would require anyway. On these shuttles with their horrible lack of capacity, their mere intent to ride will deny access to these shuttles for other wanting riders. Unless service provision is massively ramped up, the slightest initial pickup in ridership would likely result in these shuttles reaching capacity, but both operators remain extremely vague on such expansion roadmaps. It is also important to remain clear that autonomous vehicles, especially autonomous cars do not change fundamental urban geometry, meaning that traffic congestion would massively increase should the driverless cars scheme ramp up to meet demand.

The chosen routes for the Punggol AV trial reflect real inadequacies in the largely radial bus network, with most residents more than 500m away from Punggol MRT only connected immediately by bus to just the NEL. For as long as Waterway Point was all there was in town, this arrangement worked well in the backdrop of a less-populated town with fewer amenities. In particular, the connection between northern and eastern Punggol, which is the subject of one of the proposed driverless routes, should have been a full-fledged conventional bus service with the development of Punggol Coast, the PDD and Oasis Terraces as new regional amenities established apart from the legacy town centre. There would be enough ridership to sustain such a route at a relatively infrequent 12-15 minute frequency throughout the day, in line with similar full-day services introduced under the Bus Connectivity Enhancement Programme (BCEP). But they gotta find somewhere to make Punggol’s new pet project work, so a driverless car shuttle it is, nevermind its suitability nor appropriateness.

Sorry, I’m waiting how long?

The same orbital route linking northern and eastern Punggol is, according to official LTA sources, the longest of the three trial routes by travel time, taking 55 minutes to complete a full journey. Interestingly, this is also the sole route operated by the ComfortDelgro-PonyAI consortium, with the Grab-WeRide partnership handling the other two Matilda-based routes. Naturally, given that a total of just ten vehicles would be deployed initially, the question would then be that of its operating frequency. Upon probing, the CDG representative informed me that only two cars (with an option for a third) will shuttle on route 2. Assuming no layover time (a feature unlocked with driverless operation of road vehicles), that translates to an average headway of about 18 to 27 minutes, a service level far worse than anything formally permissible on the standard bus system.

Once again, these are the kind of gaps that the recent BCEP should, and is well-equipped to plug, but these low-hanging substantial improvements are being sidelined in favour of bringing in flashy toys that offer much less for the end user, be it LTA or Punggol residents alike. Imagine missing one of these cars and having to wait nearly half an hour for the next AV to come along! You’ll reach sooner by unironically taking a feeder bus to Punggol Central and then another one out to your destination, and that’s even after factoring in delays caused by recent road diversions (CRL construction). Coupled with the point on capacity from earlier, it’s a compelling push factor driving prospective riders away from building up their routines around using such services. There’s a market for one-seat rides always, but beat them with utterly inane waiting times for such short journeys and even the staunchest haters of transferring will be made to reconsider their choices.

Who exactly has so much time to wait at their void deck for 25 minutes for a ride lasting no longer than 10? Will this end up just as an even more heavily-subsidised wheelchair transport service for those with mobility impairments? The deathly irony in this, of course, is that none of the shuttles are currently built with accessibility considerations in mind, which eliminates the last viable market for such infrequent, reservation-based local transport services.

A taxi with extra steps

This is where this piece gets opiniated, but I personally believe a defining aspect of public transport that its non-users grossly undervalue is the spontaneity associated with a system that lets you freely choose your destination, and when to board and alight each vehicle of choice, with the sole access barrier being the fare point. This is achieved with high-frequency service, a largely “unreserved” seating (borrowing from mainline rail operations) configuration, and most importantly, with minimal access restrictions. More car-centric schools of thought frequently bash public transport for being “restrictive” in the sense that routes and schedules are fixed, so where traditional public transport has done well to push back against this narrative is its ability for riders to spontaneously board and alight at their preferred stops en-route, offering an alternative form of flexibility that driving falls short in.

A bus rider, for instance, could see an interesting landmark along the way, and choose to alight before their intended destination with little additional penalty. (They’d do themselves a favour by paying less, in Singapore’s current distance-based fare structures too!) Likewise, a MRT rider could change their mind halfway during a train journey and decide to tap out at a different station on the fly. Against potential inconveniences in securing and locating suitable parking spots in areas of limited supply, the spontaneity offered by frequent public transport has long been a strength capitalised upon by cities to promote and secure long-term ridership of growing public transit systems. Unfortunately, the creators of the demonstrator AV shuttles in Punggol fail to factor this into account, perhaps out of necessity.

Perhaps readers have also been wondering how these shuttles will appropriately apportion their limited capacity for a much larger demand pool, lest some get left behind. It should have not come as a surprise, but unlike traditional public transport, these shuttles operate on a booking system, which requires the user to download an app to reserve a seat for a particular scheduled journey. (Worse still: each consortium gatekeeps riders to their own respective routes, requiring multiple apps installed simultaneously to cross operator boundaries)

So that lends us to a system more akin to the reserved seating arrangements utilised on On-Demand Public Buses (ODPB) trials held between 2016 and 2018, where riders must specify their start and end points (with no changes to the journey permitted after the booking is confirmed). Or many of the systems envisioned by tech companies pushing microtransit as a broad solution to replace traditional public transport in big cities, where buses become more like taxis — only board the bus assigned to you, which will supposedly take you to your destination faster. With the spontaneity of public transport stripped, so does its appeal as a more flexible, choice-enabling urban mobility option. Do you really want to live in a world where, despite lots of driverless buses running around, you’re only permitted to board the bus assigned to you arriving the next hour?

Perhaps the justification for this inflexibility of microtransit-esque operations is that it would offer better trip times, with rides grouped based on specific origin-destination combinations which can be served directly, bypassing intermediate stops. This was certainly how LTA envisioned the various ODPB trials last decade, and could have been the sole saving grace of the Punggol AV trial, especially with the number of detours involved in the selected routes to serve immediate HDB doorsteps. If the car has room for so few people to the point others en-route could get rejected from boarding, it would make sense to skip other stops (and their associated detours) for a faster journey, right?

Ironically, the ODPB trial with human drivers did better in this aspect. A software development employee from ComfortDelgro informed me the opposite is true — even without accepted bookings from other stops en-route, the Punggol shuttles would still detour into every stop along the way, just without making stops, as part of the trial project’s requirements. For the short journeys served by these shuttles, riders are better off booking regular taxis (also run by the shuttle operators: Grab and ComfortDelgro), which cost only marginally more for a significantly faster ride. To double down on the irony, even traditional fixed-route public buses in Singapore operate smarter than that — running on a request-stop basis, bus captains are taught to fly past empty bus stops, with their schedules written with this in mind too.

Hence the unfortunate comedy of what’s supposed to be a technology-enhanced “intelligent” mobility product (a gadgetbahn, as the opening of this article tells you) combining the worst aspects of multiple transport modes into a single terribly-delivered project designed almost as if the goal was to repel ridership to the maximum extent possible. It carries the geometric inflexibility of a fixed-route bus service, the schedule inflexibility of a taxi, and the poor throughput delivery of a microtransit service, and combines them all into one utterly terrible mobility product. There’s artificial intelligence, and there is pure human stupidity, and the planning behind the Punggol AV project, when probed beyond the surface, reveals much of the latter.

A better demonstration project

On a fundamental level, this post isn’t out to bash driverless vehicles — as mentioned above, they are a necessary technology needed to maintain, and even increase upon existing service levels in our bus network, whilst juggling the pressures of an expanding urban landscape, still-rising populations, but a shrinking pool of manpower willing to do the less glamourous job of driving our buses. Naturally, it is in the interest of the Singaporean public transport system, and the millions that rely on it, that AV technology passes the sniff test and makes its way to full-fledged deployment. Rather, the subject of contention here lies in the implementation of this specific Punggol AV trial, which has demonstrated numerous points of fallacy that greatly limit its usefulness, and consequently, will limit reception and utilisation of the technology during its trial evaluation phase. But that’s not to say there’s been more successful AV trials that deliver more promising results, upon a similar fixed-route shuttle service model.

Earlier in July, Grab launched another driverless shuttle service, this time in one-north where their main Singapore offices were located, connecting it to the one-north MRT station. Unlike the Punggol trial, this one remained focused upon the essence of the service being offered — a company shuttle bus ferrying employees between office and MRT.

It functions exactly as you’d imagine a staff shuttle bus would, with the only difference being that the driver is merely keeping eyes on the road, with his hands off the steering wheel. Instead of literal cars a la Punggol, the Grab trial utilises BYD C6 minibuses (similar to those used on landed feeder service 825) specially retrofitted with sensors and self-driving equipment, with a capacity of up to 22 passengers. Even with just one bus circling the block, that’s still a theoretical maximum capacity of 264 passengers per hour per direction, more than adequate for an office housing up to 3000 employees who work at different timings and have different commute options. And that’s already two orders of magnitude more people moved than what the Punggol shuttles have to offer, by virtue of operating a larger bus more frequently. This extra capacity also means that Grab doesn’t require its employees to do the utterly inane thing of booking seats for a 5-minute ride — a staff pass is all that’s needed to board.

Of course, while the (defunct) CAVForth trial in Edinburgh involving a full-sized Enviro200 city bus operating over long distances is the gold standard for autonomous bus projects, it may be too much to ask from the current technologically conservative LTA and MOT administrations. Despite that, it’s not an excuse to swing the pendulum so far the other way that the service more closely resembles a taxi rather than fixed-route bus service. Grab’s trial thus offers the sweet compromise between practical tardiness and bold ambition; preserving the versatility of the bus ride while controlling the pace of progress to satisfy powers apprehensive of their suitability for complex road conditions in Singapore.

In fact, a similar public-facing trial is already in the works — come end 2026, similar minibuses (specified with 16 seats, an odd choice) equipped with self-driving technology will be rolled out on two low-ridership public bus services 191 and 400, to test out their performance in unshielded road traffic. Like their current manned counterparts today, they should be operating largely similar to the present-day bus services, with few additional barriers to access beyond the current fare collection system.

Now there’s an argument of defense behind using cars for the Punggol AV trial, as opposed to bigger vehicles that are capable of carrying more people: driverless cars began development before driverless buses did, and a wider market exists for AV cars compared to AV buses and minibuses. Some might recall that the Punggol AV trial was launched relatively close to the unveiling ceremony itself, with the project first announced a mere two months prior to the gala held at Punggol Coast that day. Off-the-shelf driverless products already available would enable a swift rollout faster than what could be achieved with purpose-built vehicles specified to LTA demands, as is the case for the driverless public bus project.

Announced half a year after the latter, but set to deliver a full year earlier, the Punggol AV is perhaps also intended to showcase the capability to rapidly deploy AVs to meet gaps in traditional transport networks, a key part of the very flexibility that AV proponents seek to embrace. Except, this line of reasoning does not hold water when one realises that similarly off-the-shelf level AV products for higher-capacity vehicles exist, or are currently also in active trial phases elsewhere. Besides CAVForth’s Enviro200AV fleet (readily converted from a mature Enviro200 platform), other examples of higher-capacity, off-the-shelf options include 11m buses trialled in Seoul’s new intelligent satelite city, BYD K9 buses being deployed as autonomous airside shuttles in Tokyo Haneda airport and 5G-enabled Yutong U12 buses capable of perfoming some tasks without human intervention (or what I call, situational automation)

At last year’s SITCE, more ready-made options were showcased too: BYD’s purpose-built AV minibus (BYD J6) with Level 4 automation enabled, and a self-driving variant of the Zhongtong N12 in service on the main public bus fleet today.

With so many options to choose from, even if MOT and LTA were working with tight deadlines to put together an AV demonstration project for what would be a neighbourhood circulator shuttle service, there is hardly any excuse to compromise capacity to the extent witnessed in the Punggol trial. The presence of the safety driver on board also means a lower requirement for maturity of the software being used to control the vehicles; in fact, enabling such trials to test out incomplete (but functional) self-driving systems is counterintuitively the best way to bring their capabilities up to speed with those of already-established players and products, and further open up the market of autonomous vehicles for larger-sized buses and commercial vehicles. They say we aren’t ready to test bigger self-driving vehicles yet, but on the contrary, if we don’t test it, then who will for us?

What’s at stake

Had this been any of the other trials (of which LTA had conducted many across the past decade), all these fatal errors in the project conception and delivery would be more excusable, and it would be permissible for the Punggol AV trial to slip into irrelevance and be forgotten in the ocean of transport history. After all, countless other trials for new ideas in land transport bit the dust similarly in their initial trials — hybrid buses in the 2000s, on-demand night buses in the mid-2010s, and even the briefly-executed idea of transit signal priority, present on TIBS service 700 between 1998 and sometime in the early 2000s.

Unfortunately for us, and also for LTA and MOT conducting this trial, there’s much more at stake that meets the eye. Long after the ministers and MPs gracing the event had left, I met with the director of LTA’s autonomous vehicle development wing, who shared more about the prospects of AVs as part of the public transport system. He seemed quite optimistic about how the trial would pan out, although behind that optimism revealed an emptiness in policy. This being the first truly public-facing AV public transport trial, LTA policymakers themselves remain undecided upon the many crucial facets of integrating self-driving technology into the urban mobility mix. How will self-driving technology transform surface public transport in the future? It’s a question they do not have an answer to, yet.

LTA and MOT thus place an enormous focus on the outcomes of the Punggol AV trial, in determining the direction of AV development moving forward. Put in simpler language, how the trial in Punggol pans out singlehandedly determines the trajectory of AV integration into public transport in future, for all of Singapore. This is an immense task; one whose mission carries such significant historical weight that it is almost too much for a singular trial project to bear. One where the cost of failure is further stagnation of autonomous vehicle development in Singapore by at least another half decade or more. An earlier attempt to introduce autonomous buses in the mid and full sizes by a partnership between ST Engineering and Linkker had folded in 2022 after the developers deemed it financially unsuitable to continue pursuing the field, as well as Linkker’s bankruptcy earlier this decade.

Autonomous buses have not resurfaced in mainstream transport discourse until this year since then, and will once again be if the Punggol AV trial fails to successfully demonstrate the viability of AV operations in effectively serving passengers where traditional human-operated public transport cannot. But the need for automation to step in and fill manpower shortages in the public bus industry is now greater, and resolving these issues is no longer a matter that can be kicked further down the road. Singapore’s public transport industry workforce, specifically in the position of bus captain, never recovered from the shock of the pandemic, even as ridership begins to surpass pre-2020 levels once again. A failure for self-driving technology to enter the landscape in a timely manner would force the undesirable alternative instead — massively scaling back bus services after the short-lived gains of the BSEP and currently-ongoing BCEP to match available manpower supply. LTA’s eager drive to push the Punggol trial is also telling of the urgency of the situation, for even they know that time is running out fast.

How would the Punggol AV trial be viewed, if it fails to gain adequate ridership as a result of many self-sabotaging design choices that make the service unappealing to potential riders, who choose to stick with existing options perceived to be inconvenient? More importantly, how would this highly degraded form of taxi-based AV in public transport be capable of scaling up to meet the needs of entire communities, when self-driving technology gets expanded to incorporate entire existing networks?

Even at this critical juncture, it appears that key LTA leadership involved in steering the ship of AV development lack a clear direction and evolutionary roadmap in incorporating this transformative technology into the larger transport systems used by millions of Singaporeans daily. “It all depends on how it goes down in Punggol”, they say. The lack of ownership over a critical upgrading project is chilling, and even more so considering we’re both feet through the door of beginning our automation journey.

What kind of vehicles would make up the future of public transport in Singapore? Will these point-to-point shuttles complement, or replace the network of established bus services? Is the general direction to shift public transport towards “microtransit”-style services assigning passengers to specific vehicles? To what extent will fares be integrated with other public transport modes, and how far will the government intervene in the autonomous public transport sector to manage and integrate it with legacy bus services?

These questions might sound trivial, but they paint a detailed picture of the role autonomous vehicles will be playing in Singapore’s future transport system. Knowing, or envisioning a clear place for AVs to fit into the picture will determine the evolution of AV technology and its adoption in various fields across transport. Leaving this entirely to chance might work to briefly discover some fundamentals, but ultimately will get us nowhere.

Ringfencing

In our quest in progressively scaling up AV operations in Singapore, what’s most lacking is not the technical expertise to implement such solutions for our local traffic conditions, nor the ability to coordinate resources to get these projects moving. As seen from the launch of the Punggol autonomous shuttles, we have the ability to execute these technical tasks, and I’m confident we’ll get better in this aspect.

But as the Chinese proverb “南辕北辙” goes, the technical prowess in our hands is only fully utilised when paired with a clear sense of direction emboldened by astute leadership in the relevant agencies. Perhaps the benefit of doubt can be given for reasons surrounding non-disclosure, but it’s hard not to ignore the lack of thought put towards the things that matter. What began as shuttle minibuses to shopping malls less the driver is now merely driverless taxis with limited pick-up points. The project creep is real, and a striking demonstration of what happens when one dives into AV development without clear outcomes in mind.

Enough waffling about the big ideas around AV project management in public transport. As acting transport minister Jeffrey Siow mentioned in his speech, Singapore’s foray into AV public transportation doesn’t end in Punggol, with more planned trial locations coming up in the future (pending results from the Punggol trial). We would do well to avoid many of the serious missteps identified above, especially as the impact of these shortcomings gets amplified as the system expands in scale and scope.

What should future public transport AV trials leave behind in Punggol? If it had to boil down to just one thing, ditch the cars, and run actual buses instead. It would save all the trouble needed doing logistical gymnastics to balance limited supply with untapped demand. And maybe it’s best to leave the task of detouring right up to individual doorsteps to actual taxis, whilst letting our new driverless buses focus on connecting more residents with places around neighbourhoods they want to get to. With shuttle buses for shopping malls an already-existing thing, there’s really no need to reinvent the wheel entirely just because the driver is gone.

To reap the benefits of self-driving technology on public transport in Singapore, it has to scale to a nationwide level, or remain a mere gimmick lost in the annals of history.

To those reading this article: yes, I am well aware the local transport newsroom is on fire with increasingly incredible developments recently, and not in a nice way. Hopefully the time shall be found to evaluate the truly distressing trend public transport has developed itself towards.

Interested in building a better future for Singapore’s transport? Join the STC community on Discord today!

Leave a comment