Firstly, it should be noted that it is a significant feat to have maintained a long uneventful service record, given mounting operational pressures from ever-soaring ridership and the constraints of asset renewal.

Nonetheless, illusions cannot be held forever, and the inevitable must happen without the necessary corrective action being promptly undertaken. In continuation of an already long chain of disruptions plaguing our MRT network since July, train services on the entire North-East Line and Sengkang-Punggol LRT were suspended for hours on August 12 due to a power failure, which caused sweeping blackouts in underground NEL stations. Officially, the cause is stated to be a fault with a power substation at Sengkang depot, although hearsay states that a transformer fire is to blame.

In the days that followed, engineers from LTA and SBST hastily scrambled to partially restore NEL service, operating at reduced frequencies until power redundancy systems were properly re-established. What was already a line being pushed beyond its limits suddenly saw itself overwhelmed further. Queues surged as fewer trains were available in the wake of reduced power supply. And to invoke a popular comparison in the world of discussing railway congestion — who’s the more crowded one, our NEL, or any of the many busy urban railways of the Greater Tokyo and Keihanshin urban clusters? Sometimes it’s a tough pick.

Particularly noteworthy of that day was how, despite the disruption occurring in the late morning where fewer passengers were expected, the bridging buses deployed were still entirely crowded out, as if it were peak hour. This ties back to an important, but unfortunate fact about public transportation in northeastern Singapore, especially in comparison to its equally needy peer out west.

It was extremely fortunate that partial service restoration on the NEL was completed before the evening peak hours began, for the consequences would have been unthinkable otherwise. Hark back to 2021 when a similar outage disrupted merely the outer portions of the NEL, and recall the chaos that ensued. Long queues for shuttle trains spilling out of stations, and bridging buses clearly inadequate to meet burgeoning peak demand. And in the shadow of the pandemic, the extent of disruption failed to show its full strength — one that may prove too terrifying to overcome if the NEL had not be restored in time on August 12th.

When the derailment of 2024 happened, numerous alternative trunk (and long feeder) bus services were still available, even if greatly gutted to supply a wasteful and counterproductive free bridging bus (FBB) service that could have been instead invested towards bolstering the existing bus network. As much as the west is in serious need of high capacity transit options (besides the existing EWL), a loose weave of legacy bus services dating from a time before the EWL’s conception served as the final buffer that continue to ensure some connectivity for residents, even if the rail line were to go down.

This luxury however, fails to apply in the northeast. Older readers will remember one event that public transport in all of northeastern (and central) Singapore never recovered from: the 2003 NEL rationalisation. What could have been the 30s, 99s, 154s, 174s, 185s, 198s and 502s of the northeast no longer exist today in a form fit to take over from the NEL in the event of a catastrophic black swan event such as the linewide power outage of August 12th. It gets worse — trunk bus routes (in the traditional sense of the term — long-haul routes forming main elements in networks) progressively go extinct north of Hougang. Excepting City Directs and service 80, there is no bus connection between Sengkang and points on the NEL down south. In Punggol, there is no full-day bus connection capable of providing a travel alternative for NEL trips beyond Woodleigh. And the above statements do further injustice to a group of residents — of Sengkang West, who also fall under the “Sengkang” umbrella, but without the perks of some legacy trunk bus services their eastern neighbours enjoy.

Disabling the NEL entirely would have a smaller impact than last year’s derailment, but it would be total devastation to everyone living north of Hougang town, who are now completely isolated from the rest of Singapore on a functional level. Excepting Yishun and Tampines, which remain adequately accessible from Sengkang and Punggol towns by a series of TPE-based expressway buses, a NEL shutdown would render every other part of Singapore functionally inaccessible without an excessively prohibitive travel time. Without a car or some sort of ride-hail, of course. But these modes of transport are incapable of scaling to meet surging demand from the northeast.

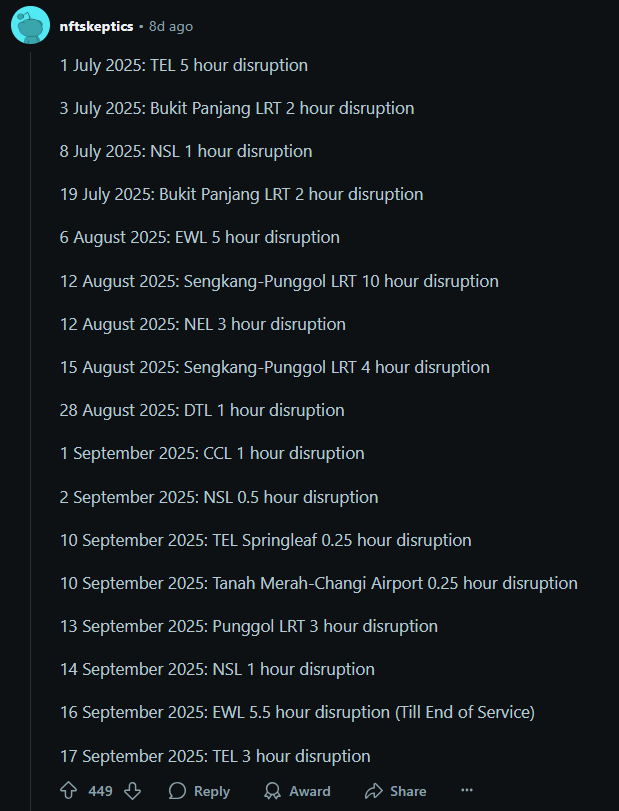

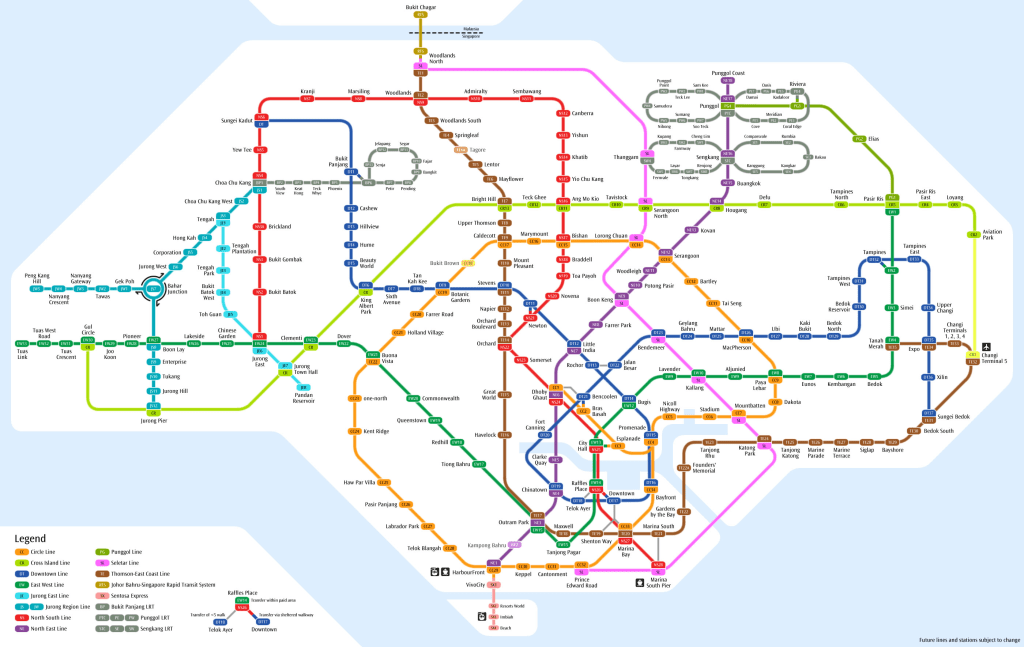

Let’s zoom back out. With the NEL (and SPLRT) reeling from their August meltdown, other lines have also been equally feeling the heat. Between July 1st and September 1st 2025, every single rail line in the Singapore MRT and LRT networks has experienced a major fault, at least once:

Originally, this was going to be a piece on transit development in the northeast, which has lagged behind population growth so significantly that incidents such as those on August 12th are inevitable. (Bear in mind that unlike the NSEWL, the NEL has barely any renewal programs under its belt, save the ongoing C751A refurbishment) Like with the October 2020 disruption that knocked out the western half of the rail network, this was a clear display of infrastructure that was being pushed beyond its original limits, as a result of a continuously increasing population, and other unwise choices in solely placing rail at the apex of the local transport hierarchy. This rings true especially for the NEL — the August blackout (and alleged transformer fire) comes right after an April timetable revision to increase the maximum number of trains running during the morning peak to 40, up from the previous 38.

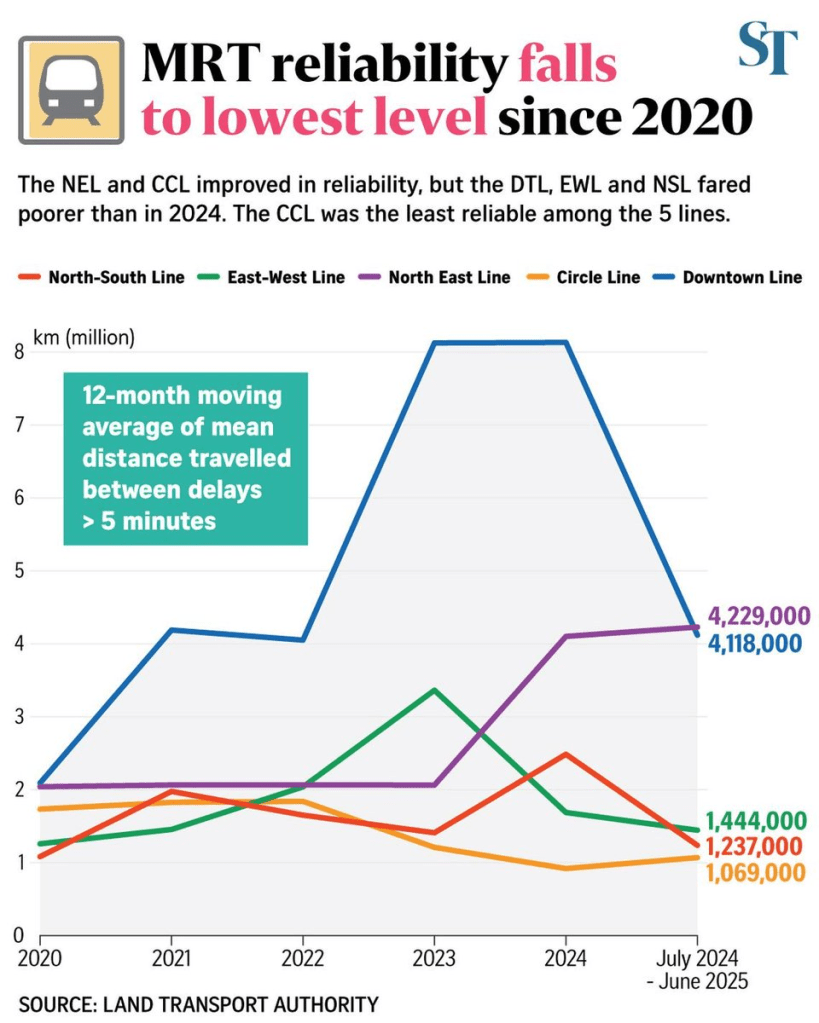

Over the past three months however, the act of massively inconveniencing commuters with frequent breakdowns has not been limited solely to the NEL however. Whilst the most severe of the lot, what happened to the NEL and SPLRT is but a microcosm of a larger trend across Singapore, one whose implications are only beginning to be appreciated now. To quickly brief on the current state of the rail network’s reliability: it’s in total shambles, with the MRT reverting to pre-2020 levels. In terms of the government’s favourite reliability indicator, MKBF for multiple lines crashed. The DTL lost its multi-year disruption-free streak (with its MKBF halved overnight), while all other lines excepting the NEL saw their MKBF figures sink below the 2 million km mark.

The rail network’s reputation has also sunk to a historic low in light of a three-month disruption streak. While the rail network would normally have its defenders even in tough times, a recent Parliament speech by acting transport minister Jeffrey Siow instead opened the floodgates of brutal criticism, with many accusing him of moving goalposts to paint a picture of Singapore’s rail network (against regional peers) that failed to match up to reality. Though further removed than the NEL is, underpinning all these disruptions is the same root cause: despite all the growth that public transport has driven over the years, it has largely lagged behind significantly in catching up to development itself.

On September 17th, following a 3-hour signalling fault on the TEL, SMRT Trains president Lam Sheau Kai told media that the spate of recent rail disruptions were “isolated incidents, and not systemic in nature”. The internet viciously tore him apart. The rail network’s latest woes are indeed systemic in nature, although maybe not in the way he’d have expected.

Northeast boondoggles, pt. 2

Let’s examine the case of the northeast again. With the lack of redundancy capacity along the NEL clearly illustrated above, let’s take a look at connectivity within the northeast itself. More severely affected than the NEL’s (official) 3-hour disruption on August 12th was the Sengkang-Punggol LRT lines, which shared the same power systems as the NEL, and were subsequently left shut for what’s effectively the rest of the day. Three days later, another power fault disabled the entire SPLRT for a further 4 hours, on top of the earlier 10-hour disruption.

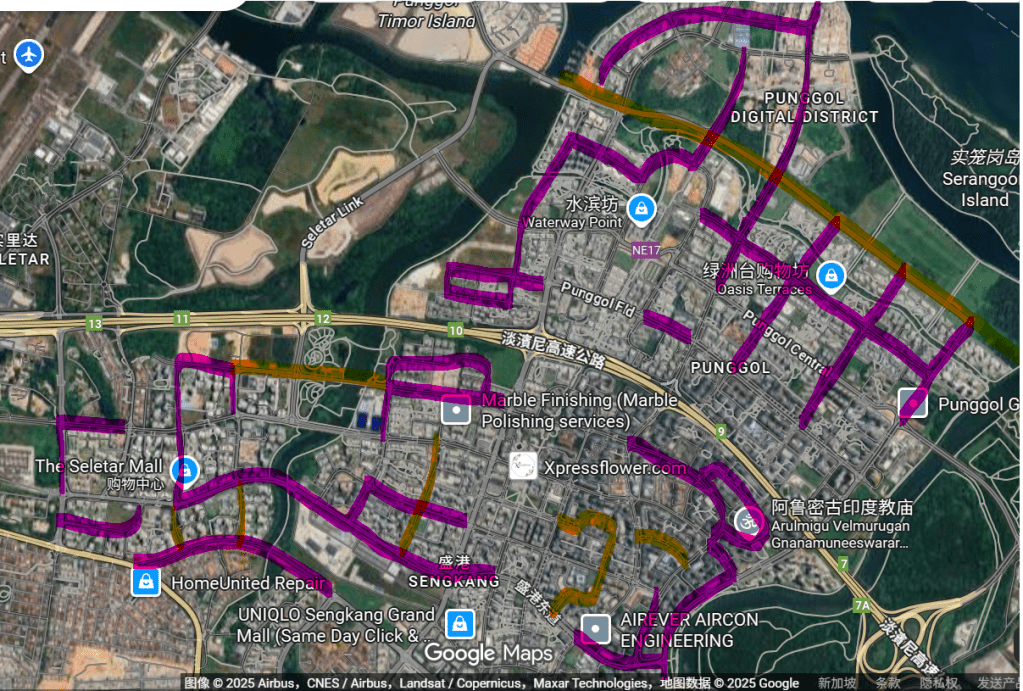

This does not need repeating if one lives in the northeast and experiences the piecemeal bus network daily — but the bus network in northeastern Singapore is one of the most barebones that can be for the higher population density relative to other towns. Do not be fooled by the HDB blocks crammed shoulder-to-shoulder like peak commuters on NEL trains — on the roads between them ply a pitiful number of bus services. Excepting a handful of main corridor roads concentrated around the town centers, much of Sengkang and Punggol is served by only one or two full-day bus services. Typically, it’s a combination of one feeder service and one other full-day route, and in typical northeastern fashion, it’s unlikely that they’d reach the level of frequency expected of its dense catchment area. Exceptions exist (371), but they’re few and far between.

Here’s a map of Sengkang and Punggol (incl. Punggol Coast) towns. Indicated in pink highlight are sections with two or fewer full-day bus services, whilst orange highlights denote sections with no bus service at all.

For context, plot ratios (total floor area divided by land area) in the Sengkang and Punggol areas range between 3.0 and 3.5, which is a very high number for HDB estates built around their era. Mature estates with more robust bus connectivity such as Ang Mo Kio, have an average plot ratio of around 2.8, and yet receive much stronger bus service that offers connectivity and redundancy to existing MRT lines in the area. It doesn’t take too much effort to realise the severe underprovision of public transport in general for northeastern Singapore.

Is it any wonder that the LRT is the only credible way to get around town for residents of Sengkang and Punggol? To further hammer home this point — I recently intended to survey crowding patterns on the Sengkang LRT during morning peak hours, but few practical options exist for someone intending to travel there from another town. In terms of the LRT itself — despite a 4-fold increase in population from 2005 to 2025, the fleet size has only increased by 40% from its initial 41-strong C810 fleet. By the time the new two-car C810Ds entirely replace them, the fleet will only be 60% larger than it was when first opened. With lacking bus connectivity, should we be surprised that crowds on the SPLRT (which is really just an APM larping as its higher-capacity, steel-wheeled cousin) only continue to grow, year after year, putting greater pressure on undersized facilities and an already-overstrained NEL?

Once again, I call attention to 10,000 new HDB flats being built in Fernvale — in an area appropriate to be labelled “transit desert” in the Singapore context. Heck, public transport in the Fernvale area has yet to catch up to 2015 demand, much less 2025 or 2035.

The broader case for expansion

While the west and northeast remain two key areas that should be prioritised in upcoming public transport development, the truth is that the rest of Singapore follows very closely behind in needing urgent upgrades in capacity and connectivity too. In a close third place is northern Singapore, particularly the Yishun area which has relied solely on the NSL for nearly 40 years and counting. Despite having strong trunk bus routes that largely survived the wave of MRT rationalisations in the 1990s, asking 230 thousand residents of Yishun to share extremely limited space on the NSL with other towns upstream and downstream is hardly a sustainable strategy in keeping Singapore’s oldest line running reliably.

Over on the DTL, an absurd situation is evolving — one where the singular terminus station, Bukit Panjang, contributes the supermajority of ridership on the line all the way into the city, leaving little room for passengers downstream (at Hillview, Beauty World, Botanic Gardens, Stevens etc.) to board. Long, snaking queues form up every morning, so much so that the uninformed can be forgiven for thinking another breakdown had occurred. Even as late as 10am, trains headed for the city are crush-loaded as they approach Botanic Gardens station.

The EWL’s woes, particularly in the west, are well-understood, especially after last year’s derailment exposed its critical flaws in western connectivity. It’s easier said than rectified, but it goes without saying that we’re still a long way off from resolving this decades-old shortcoming in the rail network, which has already tripped us twice in less than half a decade.

The CCL is in as much need of an overhaul and upgrade as the NEL is, given the similarly punishing crowds it handles daily. Launching the new C851E trains, which could give the current fleet a 35% boost, could not come sooner. The same could be said of the CRL, which will greatly alleviate the CCL’s congestion through redirecting long-haul orbital demand away, to a line properly built for ridership levels seen today. Even so, the immense stress put upon the CCL over the years, particularly from the days when nearly the entire fleet was put out into service to barely meet demand, also signify an impending need for renewal, and perhaps even an expansion of capacity to rectify historical planning mistakes.

Regardless the case, one thing stands out loud and clear: now that development has caught up to our initial investments in public transport, it is now time for our public transport system, especially the rail network to catch up to the development that it has spawned. Predominantly, this entails an expansion of the rail network to open up alternative corridors to free up capacity on currently-overcongested, overstressed rail lines.

An unfinished legacy, circa 2001

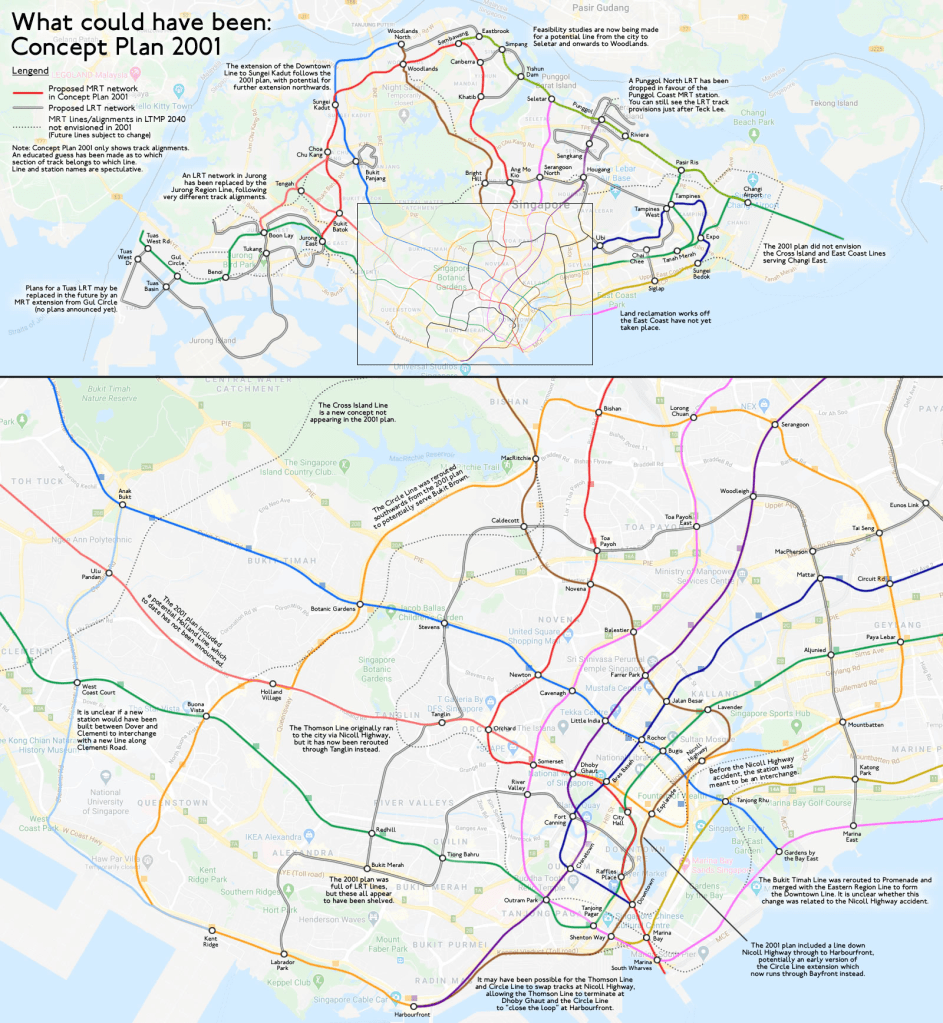

Much of the rail network as you know it today, if not conceptualised as part of the 1980s Initial System, was derived in some form from various proposals of Concept Plan 2001.

Whilst affected by the 2004 Nicoll Highway collapse, most of the Concept Plan was nonetheless realised in some way or another, even if in a different form from what was originally envisioned. (It’s a different story for the LRT lines, where the concept was largely dropped in favour of a more comprehensive local bus network instead, less CRL.) By 2035, most of the MRT proposals in CP2001 would have been delivered, with revenue service of the last few projects commencing in the early 2030s. A few names on the map stand out, with no progress having been made since their initial conceptualisation nearly 25 years ago.

- Seletar Line: a parallel north-south line between the NSL and NEL between Seletar and the city.

- North Coast Line: a line linking northern, northeastern, and eastern coasts of Singapore running largely parallel to the present-day bus service 969

- Holland Line: a line linking western Singapore to the city. Announced as the Tengah Line in early 2025.

Most egregious in this case is the Seletar Line (SLL), which the LTA has been continuously teasing to the public, but with no meaningful progress made beyond an indicative general alignment on a map of the rail network. First announced in 2019 as part of LTMP 2040 as a line being studied, the exact same infographic was recycled in a 2025 announcement alongside one announcing the TGL and JRL West Coast extension, a tacit admission that not much had been done to further the progress of the SLL in the span of six years. That’s a time span in which an old LTMP gets replaced with a new one, by the way.

On 25th September 2025, Senior Minister of State for Transport Sun Xueling stated in response to queries on the SLL’s progress that “feasibility studies are still ongoing”. Note that this was also the SLL’s status in 2019 when first mentioned as a potential future line in LTMP 2040.

While LTA continues to debilitate over the SLL’s specifics, or worse, its necessity, the clock does not stop for them, or the woes of a declining public transport experience. As mentioned above, further increases in population and job density in northeastern Singapore is written on the wall. Existing strategies such as relentlessly spamming new City Directs, at best, buy limited time; an extra five years at best, before the northeast is plunged into a dark era of failing and inadequate public transport. More effective band-aid tactics, such as the system of perpendicular express buses I proposed earlier last year, only delay this outcome more than existing measures do — another 10 years, perhaps.

Concept Plan 2001, from which many unfinished and unrealised rail projects were conceived, was created in a vastly different Singapore. Its planners, who crayoned the extensive mass of lines that continue to lie beyond present imagination, projected a population of merely 5.5 million in the year 2051, with plans determined around it. That would be surpassed less than 15 years after its release (in 2015), and as of 2025, Singapore is now home to 6 million people, far beyond what old planners had imagined, without the hyperexpansive rail network they had planned for such a population size. Blame the PAP’s immigration policies all you want, but it’s no excuse for overdue homework. As much as they want us to forget the Seletar Line, the overstretched rail network and its solitary confrontation against an ever-growing barrage of commuters will forever remember, until the necessary has been done to remedy the scarcity of public transport capacity.

Real questions to ask

The Parliament sittings earlier this week confirm a reality that commuters acutely experience, and it’s an inevitable one that politicians are slowly realising too. That earlier question regarding the Seletar Line’s progress was posed by Ng Chee Meng and Andre Low, who both contested the Jalan Kayu SMC seat in the general election earlier this year from opposing political parties. Unlike other issues in transport where politics gets in the way, the bipartisan demand for increasing transport capacity demonstrates an urgency almost never seen before. Sun Xueling’s response deliberately makes vague whether the SLL has been internally established as a necessary undertaking for Singapore’s future. The house has made it clear on behalf of the innumerous committees taking their time on this issue: yes.

It’s not a choice, really. Instead of wasting more time going in circles in the same spot as we have for the past 25 years, the more meaningful topic to discuss is how we can more quickly realise the next stage of the MRT’s expansion, without as many compromises that reduce their congestion management effectiveness. This aspect of CP2001 is not as apparent as mentioned above, but whilst many lines from this Concept Plan have been realised, they were eventually delivered in a lower-capacity form than originally envisioned. Most egregious is the Downtown Line — the constituent Eastern Region and Bukit Timah lines in CP2001 were originally envisioned as full 6-car lines similar to the then-built NSEWL, before being downgraded to 3-car specification as a result of integration with Circle Line infrastructure at Promenade and Bayfront stations. What was meant to be a brief departure from heavy-capacity rail turned out to be a multi-decade hiatus, with almost three decades having been elapsed between the opening of truly high-capacity MRT lines by the time the CRL opens in 2030.

Of course, the CRL’s design to eventually handle 8-car trains is a reassuring return to the MRT’s heavy rail origins, and even appears to be overcompensating for the lower-capacity lines built this century. The task now is to ensure that subsequent lines post-CRL will continue to uphold this standard to truly lend valuable support to the ageing backbone of the rail network. These specifics are of interest, be it in the Seletar or Tengah lines, or whatever line comes after that in the future.

Back on the topic of project delivery, it’s also worthy of noting the immense disconnect between rail delivery timelines and the urgency of the projects carrying them. I hate to say this, but the American mind virus of long, dragged-out project timelines may have contaminated even the Singapore known for working efficiently. Her most recently-launched rail project is a prime example. At just 4km long with only two additional stations planned, the Downtown Line Stage 2 extension is but a short extension spur from its current Bukit Panjang terminus to a new interchange with the NSL at the infill Sungei Kadut station, piggybacking off existing infrastructure such as the Gali Batu depot. Projected opening date? 2035, a solid ten years just for four kilometers of track and two new stations through empty open land north along Woodlands Road. For comparison, the NSL’s initial five stations were completed in under four years, despite running through densely-built housing estates.

Now of course things were very different in the 1980s, but our 2020s selves have on our side an arsenal of technology and efficient work processes that empower us to deliver in a similarly quick time. And we’ve been playing with one hand behind our back all this while — building overground, as opposed to tunneling underground segments, takes a much shorter time. For comparison, construction work on the entirely-overground Jurong Region Line only formally began in 2023, and as of September 2025, most of the line is in structurally complete condition, ahead of its launch in 2027. Nobody really believes that the Seletar Line can only open in the mid-2040s, and clearly 15-20 years to get a MRT line delivered is too much time spent, especially not when its alignment is more or less determined.

And the elephant in the room here are unmet capacity needs, in effect today and only building up further into the future. Every additional year of delay in opening new relief lines is an additional year of misery for underserved areas seeing ridership increasing to levels that can no longer be physically served in an adequate and appropriate manner. Perhaps the argument against rushing to build new lines is the balancing need for resources to be devoted towards overhauling existing ones, as components on older systems reach their lifespan ends.

Having these new lines online, contrary to that belief, significantly helps the situation by offering their legacy counterparts the policy space needed to recuperate during the inevitable technical setbacks of integrating new systems with old infrastructure. Had the TEL existed in the late 2010s during the NSL’s resignalling, the impact of a constantly-stuttering CBTC adjusting to its legacy infrastructure would be more well-cushioned than the extremely rough rollout Singaporeans experienced throughout the year. On the other hand, residents in the east, who received the Downtown Line (stage 3) that year, rode out the storm a lot more smoothly than the rest of the country did.

Two decades of dilly-dallying on the Seletar and Holland/Tengah lines is far too much wasted time which could have been put towards the second major expansion of the rail network, necessary to meet the needs of a still-growing, 6 million-strong population of the Republic of Singapore.

Barely three days before the big power outage on the NEL and SPLRT was the National Day Parade commemorating Singapore’s 60th birthday. Distributed to the audience of this year’s NDP were big placards for them to express their wishes for Singapore on the occasion of her diamond jubilee, which gave rise to this iconic scene of two vastly different desires side-by-side in the audience:

With a renewed emphasis on enhancing public transport being a key priority of the new MOT administration under Jeffrey Siow, the day where we fulfil the wish on the right should come sooner than later. In the short term, the people demand band-aids to paper over the lack of capacity wrought by the history of our past planning; moving forward the unanimous bipartisan support for accelerating growth of the rail network offers a clear direction of action to policymakers. The ball is now entirely in their court.

Interested in building a better future for Singapore’s transport? Join the STC community on Discord today!

Leave a reply to Punggol’s Second Gadgetbahn – SG Transport Critic Cancel reply