How many of you have heard of transit priority corridors (TPCs), the LTA initiative to enhance journeys on buses and bicycles? Chances are, if you’re reading STCC, you’ve most likely heard of it one way or another, either from LTA themselves or the discussion that’s surrounded them in the following years.

Now let’s turn the question around. Have you seen a TPC in person? The answer is likely to be a no, unless one frequents that specific corner of the civic district served by Bencoolen Street. While TPCs exist on paper elsewhere too (in Tampines and in Yishun), their supposed transit priority features are so watered down that de facto, they cannot be referred to as such. To the layman, the existence of these “TPCs” simply might not have crossed their awareness at all either!

On a much broader scale, the extent of transit priority initiatives across Singapore, whilst not non-existent, simply does not match the overwhelming desire and demand for more and stronger transit priority from the public. Having been to a significant number of outreach sessions conducted by LTA in various settings, an almost-universally desired immediate change to the Singaporean streetscape today would be the addition of bus lanes where none currently exist, and where they do, for them to be strengthened, with more robust protection from incursions by general traffic.

And no shortage exists of upset commuters ruminating about delays incurred by traffic congestion, where otherwise reasonable journeys take up to thrice as long to complete. So much so, that buses in Singapore carry a more lowly image in the public eye than their rail counterparts. In the past, it was the jokes about how SBS stood for “Si Bei (damn) Slow”. Today, it’s the collective outcome of endless complaints about longer waiting times and less predictable rides, even with the advent of technology aimed at rectifying the latter. With such high demand for realising stronger transit priority, you would imagine that there would be an imperative for LTA to make transit priority a key policy objective, and that a bus lane could be found on almost any major road in Singapore by now. Or at least, that the vision of ubiquitous bus priority in Singapore is currently being aggressively worked upon, with a completion date set for the near future.

Disproportionately, that vision fails to materialise, against the backdrop of universal demand for more. Today, bus lanes in Singapore number in the low dozens, so few that they still serve as location markers. In the TM50 bus priority article, we pointed out how Instagram influencer Runner Kao managed to successfully reverse engineer the location of a blurry night shot along Jalan Bukit Merah, solely from the presence of the bus lane alone. Clearly, we are nowhere near the romanticised ideal of widespread bus priority offering smooth, reliable and fast alternatives to car transportation.

The more meaningful question to ask would be why bus priority isn’t far more prevalent, despite their popularity and the increasing demand for them from public transport users. While it is easy to pin the blame on inaction on the part of LTA and related government agencies, as well as a muted car-centrism in the attitudes of planners, there probably exists a more significant factor behind the mediocrity of transit priority implementation in Singapore.

To be clear, it’s not incompetence, nor malice, that holds us back from doing wonderful things in enhancing the priority afforded for our public buses — look no further than the demonstration project that kickstarted the entire TPC exercise, Bencoolen Street. While limited in scale and scope, it painted a promising picture of what the initiative could have become. When first conceptualised, many had also hoped for a widespread expansion of TPCs to include many major road corridors, in deep necessity of stronger bus priority. What then, stands in the way of abundant transit priority that further strengthens the standing of public transportation in Singapore?

A reminder, by URA

Earlier in June, URA launched their Draft Master Plan 2025 (DMP25) for initial public viewing, with eventual gazetting slated for the end of the year. Like many others, yours truly took time off to visit the exhibition at their Maxwell headquarters (which runs until November), and discovered things that surprise and puzzle the mind.

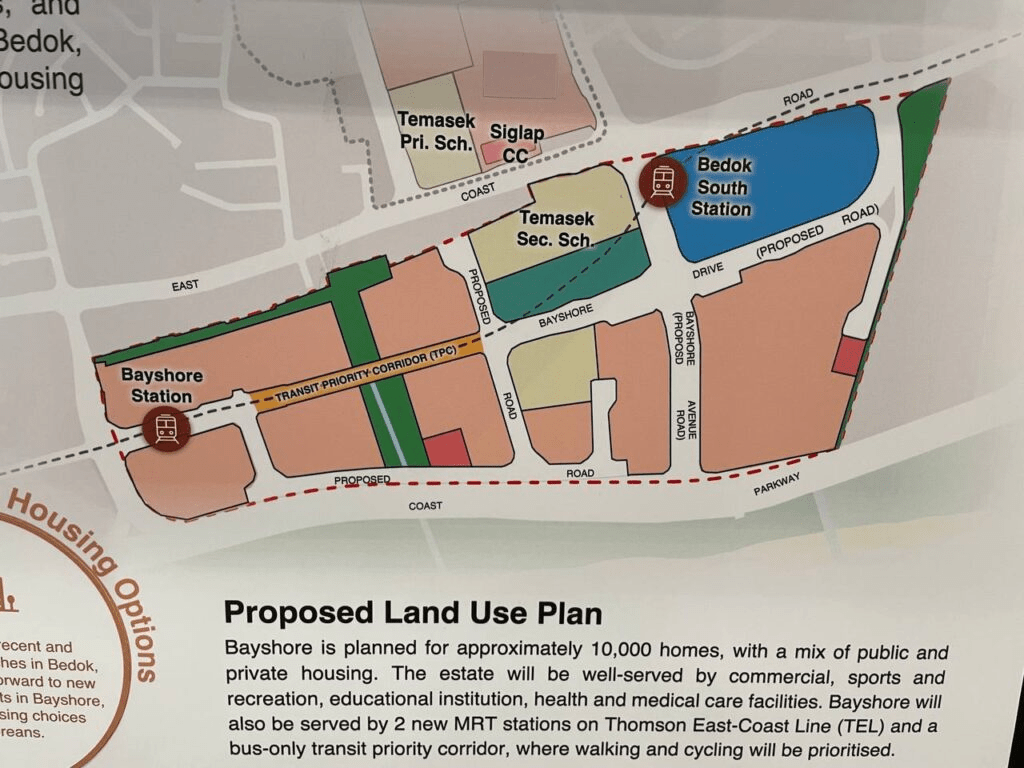

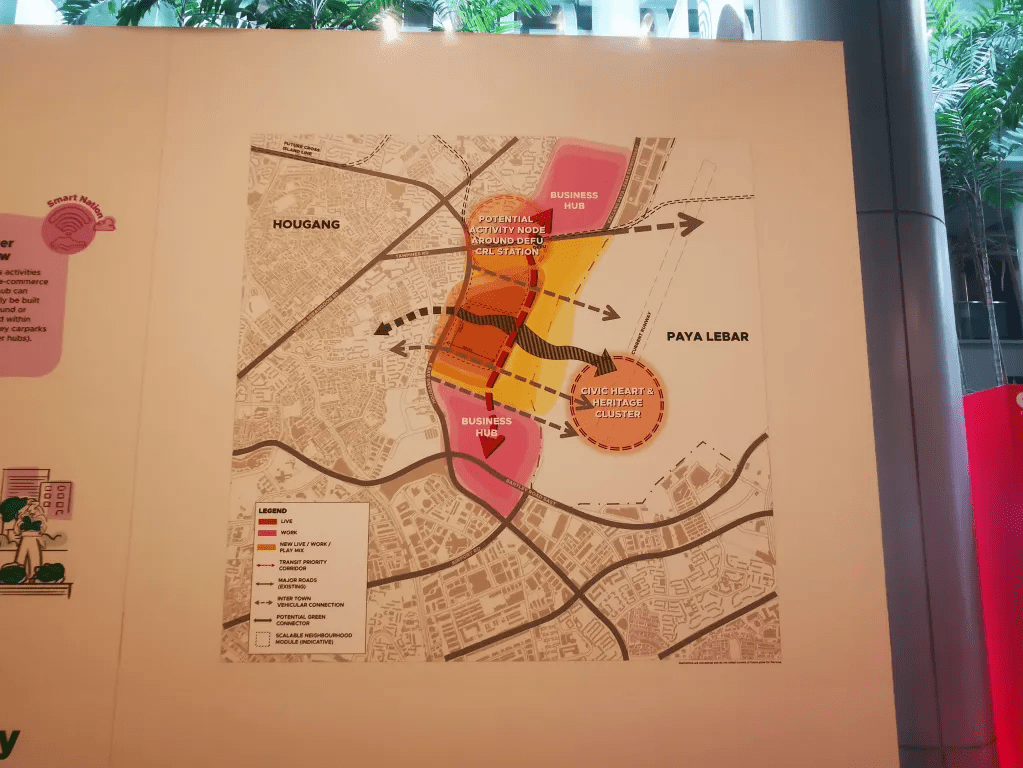

On top of the current TPCs in Bencoolen, Tampines, Yishun and Sin Ming (announced in 2022, but yet to be delivered?), three future TPCs take the spotlight of the DMP25 exhibition. One is a currently unopened TPC along Bayshore Drive, while the other is a newly-announced TPC in the Defu area linking Tampines Rd to Bartley Rd, located along the western flank of the future PLAB development. (I will get to the third later) It is notable that both projects involve relatively isolated segments that run parallel to a major road corridor with high-intensity bus service today. Of course, no discussion on TPCs in Singapore would be complete without mentioning the one slated for installation on the surface portion of the upcoming North-South Corridor (NSC).

If the NSC’s TPC is taken out of the picture, a study of the remaining TPC initiatives proposed and launched provides a insight into a more fundamental reason behind the disproportionately slow expansion of transit priority measures nationwide. Simply put, the means by which we conceive of TPCs, and the process of realising their benefits in better bus journeys, is done in a manner that does not encourage scale. Let’s examine the case of the upcoming Bayshore and Defu TPCs to illustrate this misdirection.

As a project, or a feature?

Completed before TEL4 opened in June 2024, a brief 400m segment of Bayshore Drive east of Bayshore MRT is designated as the next upcoming transit priority corridor, meant to serve residents in future Bayshore and Bedok South BTO estates.

Unlike previous implementations, the Bayshore TPC stands out as the first application of a permanent bus-only road, entirely closed off to other traffic sans presumably emergency vehicles, with road markings of the junctions leading to it also reflecting so. In isolation, this represents a significant improvement in lending buses an edge over private transport. With its prominent location in the center of the upcoming Bayshore HDB town, it appears to paint a promising future of yet another breakthrough in transit priority in Singapore.

A map of the TPC within the larger East Coast area however, tells a vastly different story, and is a reflection of the larger failings of the TPC initiative in effectively bringing about large-scale impact on bus reliability.

Today, about ten different bus services, give or take, pass by the Bayshore and Bedok South areas along East Coast Road, the main corridor along which much of the East Coast and Siglap areas are organised. With a good number of them terminating at Upper East Coast bus terminal (which will be replaced by an upcoming Bedok South ITH), East Coast Road remains the most optimal route for these buses to take, linking to their next major destination in Marine Parade and Siglap in a straight line. Another important point to note is that despite Marine Parade Road ending abruptly on its eastern end, the westward extrapolation of Bayshore Drive will fail to connect to it due to significantly-built up private housing in the way.

Armed with these realities about the surrounding bus network, two major oddities emerge with regard to the Bayshore TPC. The first, is the abrupt cessation of bus priority beyond the very brief demarcated segment, despite the continuation of the road in both directions (especially in the eastbound direction towards the Bedok South town center / ITH). The second, is the choice to locate the TPC on a parallel minor road, requiring buses using the TPC to make detours to access it, cancelling out any potential travel time benefits incurred. Curiously, despite the presence of an existing corridor where implementing a TPC could have offered much greater benefits to passengers, the choice was not made instead to upgrade bus priority upon it, but instead to establish an entirely new, isolated segment of road for “TPC” in Bayshore.

The Defu TPC, planned along the western flank of upcoming PLAB developments, tells a similar tale. Running parallel to a major existing medium-capacity corridor along Hougang Ave 3, it is similarly misplaced relative to where high demand currently exists for better bus priority.

With more than a dozen buses running down Hougang Ave 3, it similarly makes little sense to invest in a TPC not located along it. The proposed Defu TPC alignment passes through significantly fewer housing estates (all of which are merely indicative at the current stage) and industrial areas. By contrast, the existing Hougang Ave 3 corridor is part of a larger MCC linking Ang Mo Kio and Upper Thomson to Eunos and Marine Parade, passing through the highly-populated Hougang South estate and Defu / Jalan Eunos industrial clusters, on top of the proposed additional housing in Defu.

Likewise, the Defu TPC will only offer very limited benefit once operational, given that most bus routes in the area serve the Hougang Ave 3 alignment by virtue of its directness or considerable ridership from local residents. At the furthest extent, there are only three bus services that can be realistically amended into the Defu TPC at most, namely a choice between 87, 151, a potential 146 extension or an entirely new route solely linking the two indicated business clusters. Amending the rest would mean longer journeys for commuters from detouring to the TPC, and/or abandoning a significant demand pool that contributes to their ridership today. Against the dozen bus services plying along the existing MCC which also sees significant traffic (and hence the necessity for better bus priority) today, it is hard to rationalise prioritising a future road segment with lower catchment over an existing major corridor with a more urgent need for bus priority.

Of course, that part of Hougang Ave 3 does indeed have bus lanes, but they currently operate solely during the peak. Can they be upgraded to be effective all day? Can further enhancements be made to also enable buses along this corridor to flow more smoothly through intersections? The answer to both questions is a firm and resounding yes, and would be a more justified use of the resources that will go towards developing the Defu TPC.

Likewise, similarly less glowing reviews can be left of the Bencoolen Street TPC, even though it has set a high bar for positive street transformation. As much as it is a shining role model for a once-unsightly four-lane road converted to provide dedicated space for cyclists and buses, the benefits it provides in faster bus journeys and more comfortable bike commutes remain largely confined to the limited span of the corridor. Nevermind the fact that the Bencoolen Street TPC is part of a far longer road corridor spanning all the way backwards as far up as Sengkang East, or that it is just one direction in a paired one-way road couplet, which means the same benefits are not afforded for bus riders travelling in the opposite direction. Putting aside a major setback earlier this year where part of the bus lane along Bencoolen Street was removed, the Bencoolen Street TPC shares one thing in common with its lackluster successors — being highly limited in scale and scope, and largely unsuccessful in meaningfully transforming journeys across the larger network.

The DMP25 exhibition mentions a third upcoming TPC which has been left out of this post. Spanning between Havelock Road and Orchard Road, the Zion Road TPC will offer a similarly piecemeal upgrade to bus priority and cycling infrastructure in the River Valley area by 2030. Similar to Bencoolen Street, Zion Road forms part of a one-way couplet with Kim Seng Road, thus making the same mistake of excluding one direction of travel from the perks of an enhanced bus lane. Zion Road also forms part of a larger circumferential connection around the old urban core of Singapore, spanning from Cantonment Road in the south to Newton Road in the north. In line with other TPCs, other segments of this corridor, which also see similarly high, if not higher volumes of bus traffic, have been excluded from the scope of the Zion Road TPC.

Thinking broadly

As illustrated in the examples of our TPCs above, the main hurdle preventing their rapid expansion across many of our major corridors is less about institutional capability, and more of the way “TPCs” are structured as an initiative. TPCs in Singapore carry a few common traits:

- Defined as “projects” with a strictly defined scope

- Exist as short fragments, in isolation from other TPCs or the larger road network.

- (for Bayshore and Defu) Located parallel to, rather than directly upon main corridors with high bus throughput

Rather than aiming to apply the elements of bus priority to a larger corridor without compromising its quality, Singaporean TPC “projects” kneecap their usefulness by defining overly rigid boundaries, resulting in a highly narrow project scope, and consequently appearing to be more performative rather than practical, in the bigger picture of bus reliability. Look at how these projects are defined and scoped — by locality, rather than by application, or by standards. If one swaps out “TPC” in the names of these projects with “line”, one could be forgiven for thinking LTA is talking about entirely new MRT lines, given how discrete these projects are made to sound, rather than as merely localised applications of a larger idea of enhancing bus priority.

Why names matter

A project-based approach, bounded in scope by locality, makes sense when the benefits of said project cannot be enjoyed beyond the immediate vicinity without substantial additional investment or expansion. Typically, this approach is favoured for closed systems, where the infrastructure is not directly linked to other pieces of infrastructure. As a result, specifications and conditions of different projects may experience significant variance, with different solutions required from one project to the next. Examples include MRT lines and expressways, which maintain discrete names and identities even as part of a larger network. For their benefits to be felt further beyond, much more would need to be invested towards expanding other rail lines, operating connecting bus services, or building new roads linking to the expressway. Coupled with their capital-intensive nature, it makes sense to scope such projects by individual units, defined by the immediate locations which such infrastructure passes through.

Even so, most successful large-scale network expansions of such transport infrastructure require some form of network thinking which sees these individual lines / expansions as part of a greater strategic network plan to enable maximum access and connectivity. See the recent massive buildouts of rapid transit in southern China, or the conception of the American Interstate Highway System in the 1950s.

Where a change in mindset is required, is where open systems, where their benefits are enjoyed far beyond the immediate vicinity of the infrastructure in question, are being planned. At the core of it, TPCs in Singapore are simply a further enhancement to bus priority over existing conventional bus lanes, typically by upgrading its effective hours to include offpeak hours. Because their benefit is provided by enabling the buses, which travel on routes that take them far away, it is absurd to scope, and worse still to restrict said scope of TPCs in the hyperlocalised fashion characteristic of the initiative today. For example, while located in the civic area, the “Bencoolen Street” TPC enables buses to bypass traffic whilst plying routes such as 147 and 857, which serve areas as far away as Clementi and Yishun. Because of their immense potential not equivalent to their scale, it is strategically foolish to restrict bus priority to such a small area, even at the planning level.

Another example of open infrastructure where project-based thinking is inappropriate, related to TPCs, is bicycle paths. Take for instance, the expansive cycling network in Tampines, mentioned in a recent TbT post.

For a system where cyclists may spontaneously travel between paths along different roads depending on their needs, would it have made any sense to divide the network into its individual constituent parts, and then attempted to plan and re-plan each cycling path individually? Would urban planners, or the cyclist end-users of the network, think of its cycling paths in terms such as “Tampines St 21 Cycling Path”, “Tampines St 82 Cycling Path”, “Tampines Ave 5 Cycling Path” etc.? No! If the absurdities of such an approach are clear when planning cycling path networks, why should the same logic not apply to TPCs, which are largely similar in specifications wherever they are implemented?

Granted, on a contract-based level, when LTA outsources the work of building networks of such dedicated lanes, it might appear that a project-based approach is being utilised, and is effective in building out vast networks of cycling lanes in the Tampines case study. This is a severe error of conflating execution with the planning and management phases of the initiative. (A similar mistake of being unable to clearly distinguish the roles of mafia and mercenery drives the basis behind positive-looking commentary around frameworks similar to the Bus Contracting Model.) At the conceptualisation stage, where the initiative is defined to be subsequently executed however, successful examples of large-scale dedicated lane expansions utilise a broad-based approach, thinking in terms of networks rather than individual lines. To the end user of these initiatives, this conceptualisation determines the form of the resulting outcome, while mistakes in implementation can always be rectified later.

At the maximum, there may be very slight variation in the types of bus priority that may be employed (based on specific traffic conditions en-route), but it’s the same basket of solutions that can be applied in almost all cases.

Project creep

Having discussed the contrast between the two approaches to network expansion, it’s worthy of pointing out another important factor that has significantly damaged the reputation of the TPC initiative. Along Tampines Ave 1 lies Singapore’s second TPC project, completed in 2021. In stark contrast to its Bencoolen counterpart, it’s difficult for one to take its “TPC” label seriously. Not only is the bus lane incomplete, interrupted by traffic intersections and left filter lanes, it it also not effective all-day — the sole meaningfully distinguishing feature between TPCs and conventional bus lanes in effect since the 1970s. This is a glowing example of what’s famously known as project creep, where an otherwise stellar project is eroded as standards slip. In the public transport world, a notorious example of this is “BRT creep”, where BRT projects gradually shed so many of their defining features (bus priority, high frequency, stop improvements, optimised operations) that they eventually become just a more fancily-branded bus running in mixed traffic! In effect, the Tampines TPC has befallen the same outcomes, where “TPC” is merely a fancy branding that otherwise signifies no real improvement. (Granted, Tampines Ave 1 previously had no bus lane of any sort, so if that’s what LTA is using to hail it as a victory…)

Project-based approaches to initiatives are exceptionally susceptible in this regard, because their objective is tied to implementing the initiative in a certain location, with the quality of the delivered outcomes coming secondary. What needs to be emphasised instead are the standards to which bus priority is delivered, to counteract against the tendency for project creep to set in. A standards-based approach measures success by how much quicker buses are running; the project-based metrics used in TPCs measure success by project completion, no matter the discounts made during the planning stage for various reasons.

It is with this risk in mind that I fear for future TPCs. Nevermind pressure from a loud minority of motorists backed by MPs to revoke transit priority; project creep is capable of destroying the fort from within without external opposition. What are the chances that the Zion Road and NSC TPCs will face the same fate as the Tampines TPC, with the bus lane placed side-by-side with existing mixed-traffic roads? We need firm voices in LTA’s road planning departments to assert, and maintain a high standard of bus priority from start to finish, and not a paper-pushing approach of defining TPC “projects”, which get compromised eventually. Sadly, it is more likely that bureaucrats and politicians are interested in seeing more names added to a “list of TPCs”, rather than taking the effort to enforce transit priority standards, and truly expanding access for all.

We now come to what must be done to realise the aggressive expansion of transit priority to meet urgent needs of today, and the large demands of tomorrow. Hampered by overly narrow project definitions and gnawed at by competing interests, the project-based approach to expanding transit priority in Singapore is unsustainable and incapable of providing abundant improvements to bus service reliability.

Ordering smart

Instead of treating TPCs as standalone projects, it would be far more productive to reframe the TPC initiative as a form of road upgrading scheme. Recognising the expansiveness of the bus network in Singapore, even if the current project-based approach were to scale up tenfold, it would still leave significant gaps in the network that do a disservice to the needs of countless people riding the buses plying upon it. Rather than treating TPCs as discrete items needing significant effort to materialise, the correct approach, widely adopted in cities who have more successfully improved bus service, is to consider them as add-ons to already existing road infrastructure. I suspect part of the reason why the initiative has struggled to take off is due to a mental impediment in planners’ beliefs that significant investment in financial and human capital must be made in order to consider the project worthy. Not entirely untrue, but this energy expended must be devoted towards ensuring the bus priority produced meets a standard that truly enables buses (and public transport overall) to be time-competitive against driving.

To be frank, a car-lite society should treat bus priority as a given, and not something to brag about, or count towards performance KPIs. It’s just there as a way of life, as part of giving public transport the appropriate priority it needs. This is the end goal that the TPC initiative should be working towards! And to do that, requires treating bus priority as complementary, if not a mandatory element of our road design, rather than as a premium perk. Our current approach towards TPC implementation is analogous to ordering a la carte dishes from fast food restaurants. Analogously, we should aim to transform this attitude such that bus lanes are the side dish, offered in tandem with the main course known as our road infrastructure.

Let’s put this in more concrete terms. For the next expansion of the TPC scheme, LTA should instead clearly define a golden standard for TPCs. If it doesn’t appear actionable for certain situations, multiple levels of standards may be defined. Next, the goal should instead be framed in terms of bus priority coverage, starting with the highest targets for expressways and major arterials, then decreasing target coverage for secondary, tertiary and minor roads. Now, instead of building individual discrete infrastructure projects, LTA is instead conducting an upgrading project, and they have no shortage of prior experience to draw from (2010s rail renewal, currently ongoing bus fleet renewal etc). In fact, the first step is more or less already done — an informal standard for the quality of bus priority offered by a bus lane more or less already exists. Just look at how LTG organises their list of bus lanes!

An example of a standard which can be easily deliverable within the decade is as such below (Percentages indicated by road length):

- 95% of all expressways and arterial roads to be equipped with minimum Grade B bus priority

- Of which, 80% equipped with Grade A bus priority

- 70% of all secondary roads equipped with minimum Grade B bus priority

- Of which, 45% equipped with Grade A priority

- 50% of all tertiary and minor roads equipped with minimum Grade C priority

- Of which, 25% equipped with Grade B priority or better.

With different tiers of bus priority indicated as follows:

- Grade A0: Full-day (red) bus lanes, fully uninterrupted*, with traffic signal priority enabled OR Bus-only road with no other mixed traffic

- Grade A: Full-day (red) bus lanes, fully uninterrupted.

- Grade B1: Full-day (red) bus lanes, with interruption.

- Grade B2: Peak-only (yellow) bus lanes, fully uninterrupted. Traffic signal priority may be present.

- Grade C: Peak-only (yellow) bus lanes.

Grade F: No bus lane

*Interruptions to bus lanes are defined as permitted incursions into the bus lane to allow for left-turning traffic or other weaving operations, typically occurring near traffic intersections and/or expressway entrances. An uninterrupted bus lane may physically break at a traffic junction to permit perpendicular traffic to flow.

This is just one possible way that LTA (and URA…?) could go about rolling out bus priority on a much larger scale to adequately cover much of the bus network. Of course, it doesn’t have to follow my stats, or the standards I defined here. That would be another conversation to be had, once a clear system of defining the various extents of bus priority has been established. But it would represent a significant paradigm shift in the way we expand bus priority, from talking about localised projects to instead visualising a greater multi-year workplan to progressively enable car-lite travel on the many avenues and streets spanning Singapore. And for that matter, when those are the conversations we’re having, it would signify that we’ve progressed into a new era.

Not to mention, these goals are just the beginning. With further expansion of the bus network in a future driverless age, further expansion to the extent of transit priority nationwide would be needed. These standards defined today will continue to stay relevant as a clear benchmark of measurable improvements that can be made down the road.

A broad-based approach in developing TPCs entails a shift in focus from the where to the how and what of implementing better bus priority. With a clear goal to provide abundant access for public transport users, the illusion of an insurmountable shortage of resources to swiftly realise these outcomes fall apart. Quickly, one would discover that despite all the myriad of situations bus priority must be implemented in to reach coverage goals, their solutions share much in common, and can be quickly replicated across various situations with minimal adjustments for specific local circumstances. The issue of cost would fall apart when the project gains momentum, enabling bus lanes to be built at scale, replicating at low cost across the country. With a clearly-defined set of standards, the job is much easier — simply replicate the successes of prior corridors across others — and in no time, would we have arrived. A Singapore where bus lanes are as ubiquitous as street lighting and bike paths, where travelling by bus becomes an appealing choice compared to driving.

I would want to close off this piece with yet another observation. As a form of transport provision, transit priority should fall entirely under the purview of LTA, who also entirely manages affairs relating to the provision of public transport services and the infrastructure upon which they operate. For something as simple as a full-day bus lane to appear in URA’s work, focused upon urban planning and urban form, as a major landmark feature, is a stark reminder that we are still far from our touted ideals of promoting and maintaining a world-class public transport system.

Were we to be serious about transit priority, the bus lane would have melted away to be merely a default feature of the numerous roads, plain without detail, that URA hastily illustrates in its models. For the matter, that would also apply to cycling lanes too.

Interested in building a better future for Singapore’s transport? Join the STC community on Discord today!

Leave a reply to Punggol’s Second Gadgetbahn – SG Transport Critic Cancel reply