So it turns out that when it comes to rail and bus, the way our government agencies handle things don’t appear to be that different after all. And as much as we aren’t nearly as free nowadays to consistently chase the latest news, the storm has blown so large that it would be negligence to ignore its impact on the local public transport experience in Singapore. Long overdue like most other articles on this page have been, but here we are. When it comes to the art of weasling one’s way out of their due responsibility, the public transport sector here needs to realise that they can’t both have their cake and eat it.

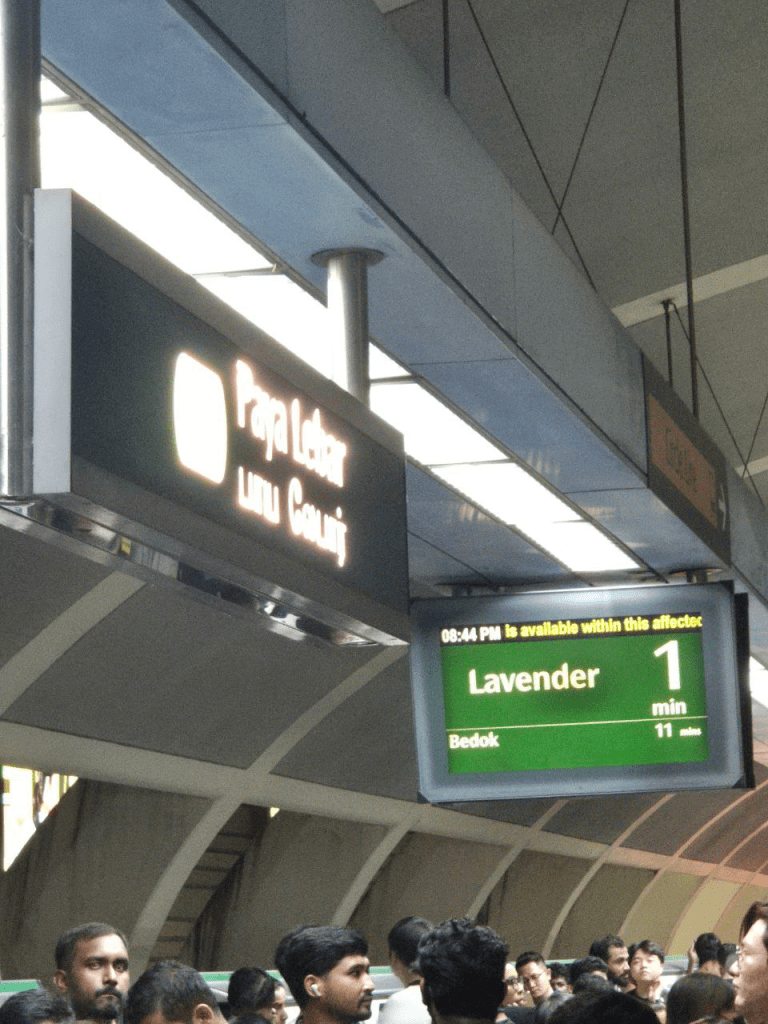

The story begins with a simple Parliament query from elected NCMP Andre Low on 13th January inquiring to the possibility of providing real-time train arrival timings on LTA’s Datamall system, similar to the way bus arrival timings are kept (and queried by official and third-party apps from) there. It’s a relatively unassuming question compared to the other grander topics explore, but those familiar with the scene will know how transformative this seemingly minor change can be. To the vast majority of Singaporeans who have grown accustomed to the MRT’s presence over the past four decades, the only method to find out when a train is arriving was to head down to the MRT station and look at the display boards placed at the station entrance. In that respect, we fare better than a number of other counterpart rail operators who only place the departures board deep within the bowels of large station buildings.

Linking real-time train arrival information to Datamall enables one to access such information through the use of apps such as the official MyTransport or any assortment of third-party apps by interested developers. Rather than being confined solely to within stations only, access to real-time train arrival information anywhere is actually quite useful for a number of reasons:

Where should I transfer?

Despite the relatively limited coverage of the current MRT network (in comparison to an ideal future with many more lines to be hopefully realised), most journeys on the rail network today that require at least one transfer to complete often have multiple possible route options with similar travel times, after all else is accounted for. One powerful use for readily-available arrival times for train services would be to inform commuters’ decisions of which route to take, when faced with such a choice, such that their travel time may be further optimised with transfers timed to minimise waiting time.

Take the example of someone riding the train from Bukit Panjang to Paya Lebar station. Two plausible routes exist — one involving taking the Downtown Line all the way to Bugis, and then the East-West Line to Paya Lebar. The other would involve changing to the Circle Line at Botanic Gardens station. With a roughly similar travel time between both options, a commuter armed with real-time train arrival information can decide if he should alight at Botanic Gardens station to catch a CCL train (based on how quickly he can complete the connection through the station’s long linkway) or stay on to Bugis for the East-West Line. Having such information would prevent a situation where the commuter alights at Botanic Gardens station, only to barely miss the CCL train when he arrives at the platform.

Eyes from afar

In tandem with similar calls to ensure better information dissemination when train services are impacted by inevitable faults and delays, real-time train tracking helps play a part in the messaging needed to prevent unknowing riders from further packing into affected lines. Beyond just official written notices stating delays and their extent, real-time arrival information is another easily accessible indicator of how well a rail line is currently performing.

Signs such as bunched trains, abnormally large gaps and non-regular terminating points for train services are some key indicators of a train fault that can be detected publicly even before official announcements are sent out. In some cases, staff from LTA and the rail operators are probably too busy doing crisis management to remember sending official disruption alerts, as was the case last December, when a late-night track fault on the East-West Line went unreported on official channels. The anime artists explain what happened better than we do:

We don’t condone the lack of information transparency that happens when such disruptions occur (and even less so the comments on “localised communications” as post-hoc excuses). But at the very least, should the chain of communication break down again when the trains break down, having a real-time tracking function for our trains that doesn’t require human intervention to operate is the last line of defence in enabling the public to be aware of potential delays to their journey, and seek alternative transport arrangements early, rather than being caught off-guard by unannounced delays only when they enter affected zones.

If only more people could know what was happening on the train platforms that night! A train tracker built on real-time arrival data placed on Datamall would have served as “eyes” for them to peek into affected EWL platforms, saving them the grief as many got stranded by a track fault left unannounced.

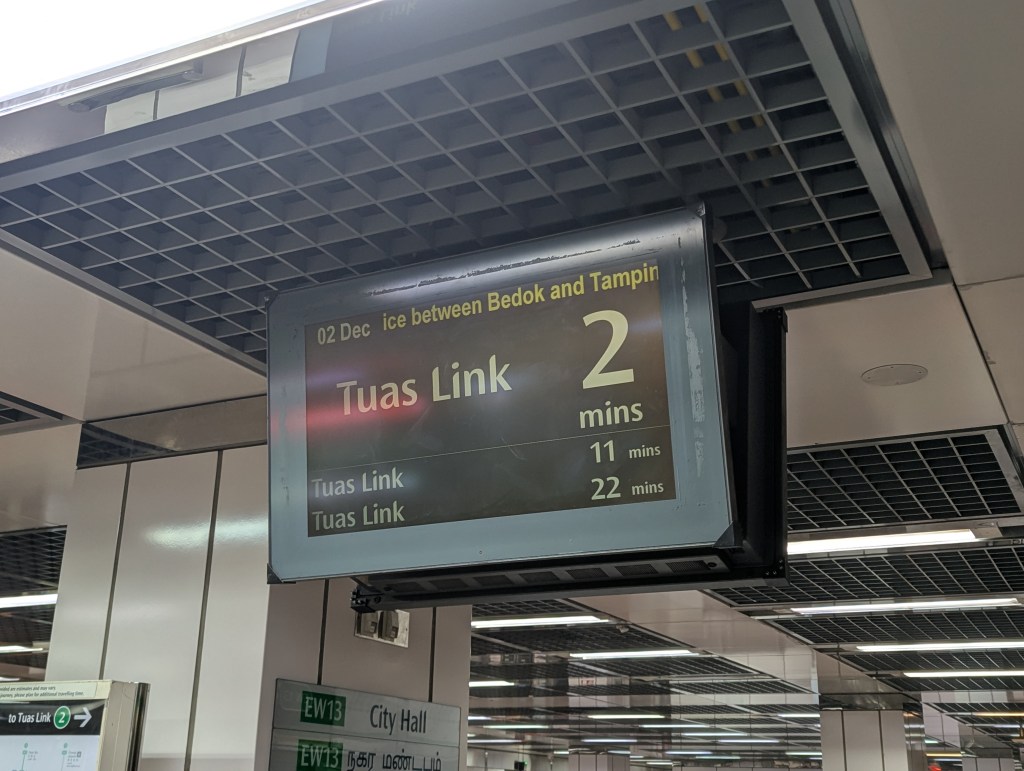

In response, acting transport minister Jeffrey Siow stated there was no need for such information provisions as trains operate frequently , reducing the need for real-time tracking to plan journeys. It’s not entirely a correct statement for two reasons, the first of which has been explored above in informing commuter choices between multiple possible routes on the increasingly grid-like rail network. The second, which he likely may be unaware of, is that certain sections of the rail network do not operate at “short” intervals as claimed. Missing a train at Tuas Link for instance, means a waiting time of as long as up to 18 minutes for the next departure depending on time of day and week. If you were travelling there by bus 182, you’re much better off staying on the bus all the way to Joo Koon, where you might even catch up to an earlier train!

When buses aren’t spared

Typically the word “disruption” is not paired with buses in Singapore, with the added expectation that buses are the back-up transport mode when the rail network starts failing. Right as the new year came around however, another long-term (unplanned) disruption hit, albeit not the typical kind many would expect.

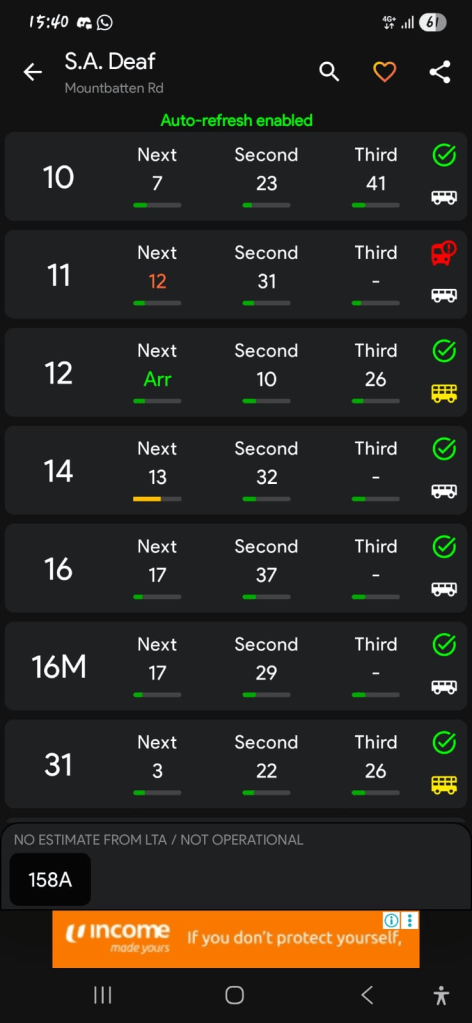

Despite having existed at smaller scales since the beginning of real-time bus arrival information, the issue of “misdetected” or “undetected” buses (also known as “ghosts”, where they do run in reality but do not show up in bus arrival information) became widespread earlier in January, with the first noticeable rise in such faults detected around the 10th. As it got worse, so did attempting to plan journeys by bus — multiple buses in a row on the same route would go undetected, with displays at bus stops and arrival time apps frequently stating incredulous headways (40+ minutes) for services that would otherwise normally operate more reasonable 10-15 minute frequencies at their worst.

For the first time in nearly 20 years, a full shutdown of the real-time bus arrival system was performed between 21st and 23rd January, to reset the system. A further update on the 23rd stated that four days would be needed to completely resolve the cache problems across the nearly 6,000-strong bus fleet causing the large-scale ghost bus phenomenon. As of publication on 2nd February however, undetected buses continue to remain an issue more prevalent than previously. Having overrun original timelines by more than a week and counting, it’s time (pun intended) to re-evaluate the way we think about the various travel time-related accessories across our public transport network.

Update 07.02.26: LTA announced on 7th Feb that rectification works had been completed on 90% of the bus fleet, with a timeline for full completion left unset. Also announced was formal confirmation of the introduction of second-generation onboard equipment aiding in bus tracking, intended as a measure to boost system reliability.

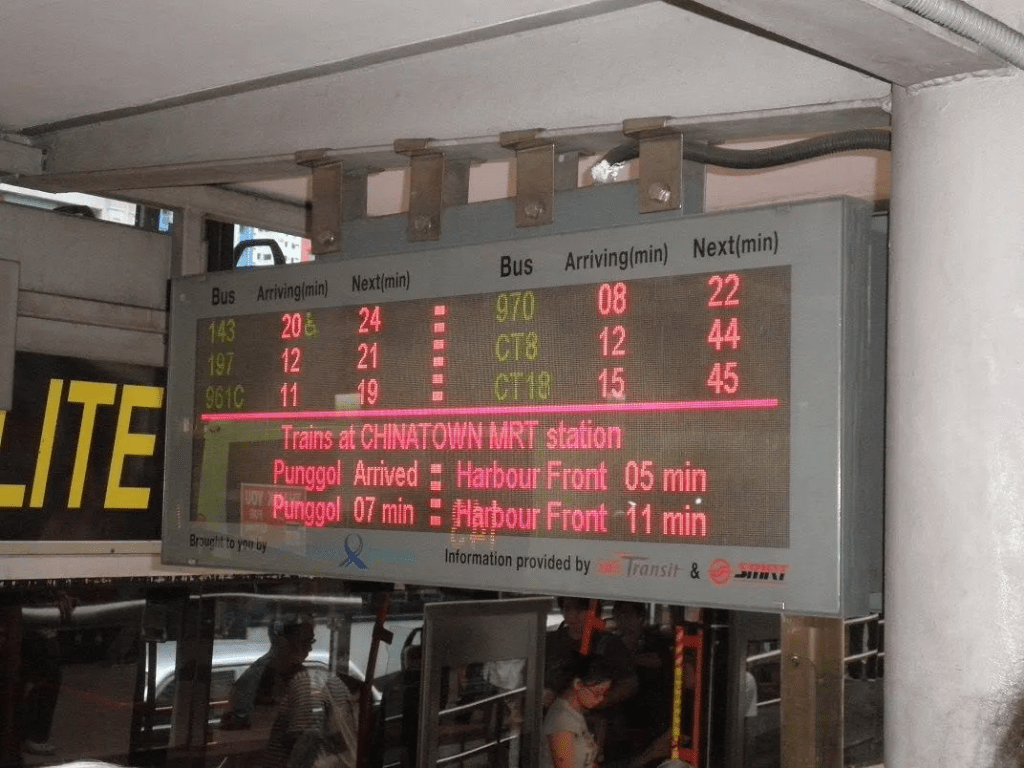

For those who have been around long enough to remember older forms of real-time arrival displays across our public transport (from the early 2010s), digging one’s memories for a bit may lead one to the surprising conclusion that the provision of such information has in fact regressed over the past 15 years.

Back when bus arrival displays at bus stops were still of the clunky dot matrix designs with far less flexibility to display different information formats than the sleek digital screens today, LTA and train operator (SBS Transit) had already come up with a way to integrate real-time train arrivals with bus arrival displays at the surface level, some distance away from the fare line from the commuter perspective. This was still an age when bus operators maintained separate infrastructure for tracking their respective bus positions, rather than the standardised CFMS platform introduced by LTA under the BCM in use today.

A more prominent example to remember for older (by age) readers would be the integration of real-time train arrival information on older iterations of the SMRT website, where clicking into the individual webpage for each station would display the arrival timings of the next two trains for each travel direction of each line that called there. Being your usual mid-2010s webpage, it’s slightly tedious to navigate by today’s standards, but had the function been retained to the present day, it would most likely have been integrated under LTA’s common Datamall framework and made open-source, where the brightest minds locally would figure out a more intuitive way of accessing and presenting such information.

When it comes to discussing what extent of such information should be made freely available, the shortest plank in the barrel unfortunately dictates how far one needs to go. As demonstrated earlier, the Minister’s comment on how frequent train services negate the need for publicly available train timetables is disproven by multiple segments of the rail network operating at intervals that would drastically alter travel times if one were to inadvertently miss the train. (But where it holds, it stands as a testament to the truth of high-frequency service enabling one to function without requiring reference to a printed schedule of any kind!)

Cautionary notes, for rail

A popular call that emerged from that Parliament inquiry was to print train timetables on a large scale and display them across the MRT network in stations, to remove the uncertainty associated with not knowing when the next train is supposed to show up. The most commonly-cited model example is Japan, which is known for printing complex timetables detailing the departure time, service type and destination of each train departure.

Some extend this argument into one of accountability — knowing precise departure times would ensure that rail operators perform up to standard, with the public scrutinising exact real-world performance against their own published schedule benchmarks. It would be a refreshing departure from the black-box mechanics that characterise the Singapore government system, but in the specific context of our MRT system, it may well be rather impractical. Aside from the concerns of locals being apathetic about the nitty-gritty details of public transport operation, the logistics don’t favour this approach either.

Urban rail transportation in much of Japan is provided not by dedicated “rapid transit” systems (such as the Tokyo or Osaka Metros), but instead by a large, nationally interwoven complex network formed by mainline railways optimised for urban-suburban travel, sometimes even jointly run by multiple operators too! At that sheer scale and complexity, to coordinate operations across operator boundaries safely (most Japanese railways lack ATO!), a more formalistic, contract-bound operating mode is favoured to ensure each component of the network operates smoothly. In such an arrangement, each operator adheres to their portion of the general timetable to avoid conflicts with traffic from other rail operators. The amount of work that goes into even minor timetable revisions means that these are carried out infrequently, at most once or twice per year, and become major events for local railfans to commemorate too.

Contrast that with our MRT system, which operate as functionally separate lines with an entirely all-stopping pattern. With a much simpler layout to work with (at the expense of not being able to quickly introduce express services on our existing lines, which isn’t exactly the wisest idea either), our rail operators instead make use of frequent timetable adjustments to try to meet fluctuating demand patterns along the six major rail lines here. Rather than timetable changes every year, they happen about once every few months here, and sometimes even happen once a month or more during special circumstances! Printing large timetables and replacing them so frequently is simply not very desirable, especially as our rail network is set to grow. Imagine replacing multiple large boards containing the train timetables across 200 stations every few months! All that work could be better put towards other things that matter more to core operations, such as maintenance.

Would it work to publish online timetables, which save on the cost of having to continually replace physical timetables in stations, and are accessible from anywhere with a mobile phone, at least in theory? Maybe, but it would be important to ask if this were a meaningful endeavour worthy of pursuit.

A key characteristic hidden in plain sight, but often overlooked by fans of the Japanese railway system, is the low frequency of train services compared to typical peak-hour intervals seen on our MRT system. For the record, there is not a single Japanese rapid transit system operating more than 20 trains per hour, or better than 3-minute frequencies. That’s equivalent to the current peak-hour service levels on the TEL, or worse!

On the other hand, our MRT lines fitted with CBTC signalling technology are all designed to be able to handle up to 36 trains per hour (100-second frequency), with actual headways on most lines between two and three minutes during peak hours. That’s anywhere between 20 and 30 trains per hour. To fit 30 entries onto a printed timetable board similar to what Japan does, whilst leaving space to display alternate timetables for weekends and public holidays, would result in comically large timetables coming close to resembling wall-height advertisements that appear in some stations. Or if printed at more “reasonable” sizes, it’d simply be illegible due to the sheer number of trains that need to be reflected on such a timetable, which can number as many as 400 trips per direction per day!

For purposes of ensuring rail operators are held accountable to their duty of providing timely and adequate train service to millions of Singapore, it might be meaningful to compare actual arrival times of consecutive trains scheduled at 10:12 and 10:40, since missing the first would mean waiting almost half an hour for the next. But it might not be that meaningful to monitor actual arrival times of two trains scheduled to arrive at 10:23 and 10:25, where train intervals are so close together that the impact of a delay is less apparently felt (but snowballs quicker due to a lower margin of error present!). At that headway, every train can be delayed by one slot (the two-minute interval) and still not register as a “significant delay” in MKBF metrices defined at the 5-minute mark! That being said however, not every part of our rail network is built equal, and something can still be done where service is insufficient to wean off the need for timetables to plan journeys.

On the bus system, timetables (such as those featured in this post header) are published and printed at bus stops for bus services that experience intervals longer than 15 minutes at any point of the day (and are required to adhere to a strict timetable, rather than following the headway-based management implemented across the rest of the network). Why 15 minutes? Internationally, that’s the accepted standard for “frequent” service (in places such as North America and parts of Europe where frequency of transit service continues to remain up for debate). Worse than that, and one’s life must be planned around a highly limited bus or train timetable. Within Singapore, the 15-minute threshold (or 4 buses per hour) is also the de jure baseline service requirement that bus operators must attain as part of the Bus Service Regulatory Framework introduced under the BCM since 2016, with limited exceptions for express and rationalised (eg 167, 852) bus services. Of course, repeated service cuts since the COVID-19 pandemic mean those standards are as good as on paper only. That aside, the point of bringing this up is to show that a similar compromise can be reached for rail, where passenger expectation of travel time consistency is much higher.

What would be an appropriate threshold for such timetables to be issued? Five minutes, beyond which differences in time cannot be attributed any more to mere rounding error. Time in casual lexicon is also typically referred to in five-minute intervals (eg. 9:45, 17:20, 21:55 etc), so missing a train operating at that frequency makes the difference between a negligible delay and one significant enough to raise eyebrows in social settings. Timetables can be provided (in online form preferably) for stations where trains operate at 6-minute frequency (10 trains per hour) or less at some point during the day.

At current service levels during publication* (13th Feb 2026), that would make all of the TEL, the Changi Airport branch line, and the Tuas West Extension eligible for timetables throughout the week, whilst the NEL and CCL west of Caldecott are also eligible for weekend timetables due to their exceptionally infrequent services in the morning and midday respectively.

*Excluding modified schedules for reduced CCL services between January and April 2026 for tunnel strengthening works

With so many more trains being run per hour, what should be scrutinised at the end of the day is less of how much each train has deviated from its scheduled departure timings, but how much service has been provided. How many trips ran when most people needed to get to where they needed to go, and how long did passengers have to wait? Looking at these gives a broader picture of how well our rail operators shoulder their responsibility of moving the nation, when looked at holistically with other factors such as crowding of course. Linking real-time train arrival information to LTA’s Datamall where they can be reflected on online apps would be the transformative first step, but its greater potential lies in its ability to keep records of train trips over time. In the context of heavily-used urban rail transit systems like our MRT, rail operators deliver not individual rail trips, but a service formed from running many trips from dawn to dusk. Let’s hold them accountable to that.

Cautionary notes, for buses

In the wake of the earlier highly destructive cache error that caused many buses to vanish from the common database powering bus arrival timings, there have been calls by some to revert to a fully timetable-based bus system. Known as the OTA performance metric under the BSRF and contrasted against headway-based metrices used to evaluate most bus services (known as EWT), it’s not difficult to determine the motive behind such a want: amidst the uncertainty brought about by the mostly nonfunctional bus arrival information systems, forcing buses to follow a fixed set of timings that would be available to commuters on an analog medium at bus stops provide stability to trip planning.

Similar to trains as mentioned above, it can be a pointless exercise to straitjacket bus services through rigid timetables, which are harder to adhere to for busier, high-frequency bus services that regularly encounter variance factors such as high passenger exchange and traffic lights. That’s besides the good ol’ traffic jam that messes up even the most carefully-thought out schedules once they appear beyond expected ranges. Especially for services fulfilling last-mile connectivity, where its the importance of being present in sufficient quantity to meet ridership need outstrips being punctual. Unless of course, we’re looking at the interval chasms that are opened up as a result of bunching, causing commuters to wait longer.

A convenient refuge?

Why is it taking so long for bus arrival timings to go back to normal, after glitches were first discovered on 10th January? (As of publication, it has been more than a month since the issue was first formally identified, according to LTA’s timeline) There are loads of valid reasons behind the technical complexity associated with going around to replace navigational components across more than 6,000 buses, but as buses disappeared off arrival time databases, it cannot be denied that this forms the perfect smokescreen of convenience. In fact, for a significant portion of bus riders, it would be entirely fair to say that the partial downing of the bus arrival timing system has had a much more muted impact on their journeys than portrayed in media. Correspondingly, their woes did not start on 10th January 2026.

Since the beginning of the COVID pandemic from 2020, the bus industry never really recovered from its crushing blow on available manpower, and even to this day with six years having passed, many bus operations continue to remain in contingency mode, with regression plans in place to account for fewer bus drivers available than needed to maintain frequent operations. From regularly pushing managerial staff into driving duties and resorting to last-minute, unannounced schedule rearrangements to lengthen headways, such practices hollow out the promise of more frequent bus services set 14 years ago. As mentioned earlier, a 15-minute frequency baseline was established in 2016, but for a good number of bus services, being able to achieve that consistently throughout the day today (2026) will be a dream.

When one opens the bus apps and sees scenes like these, showing intervals in the 20+ minutes range, it’s anybody’s guess whether the gap is real (be it caused by delays or actual impromptu service cuts), or whether there’s a bus hiding in it, just not being detected.

Select demographics such as bus enthusiasts and retirees may have the time to afford to wait around and find out to see if their gamble pays off. Unfortunately, not everyone has the luxury of time to play similar games with their demanding schedules. With cars priced out of most ordinary Singaporeans’ reach, the choice is often to pack on trains further — exacerbating existing stresses on the rail network, even for journeys that would be more logically undertaken by bus. And for areas where rail is not an option, either for local last-mile connectivity or where the radial rail network falls short, it translates to a greater time wasted on allocating for uncertain, unpredictable travel. Even if going along the lines of those who argue that bus arrival apps can resolve the inconveniences of infrequent services, what resolution is there to be had if the bus trackers cannot be counted on to work? Reminder again: “ghost buses” didn’t start on 10th January, and neither did the phenomenon of cancelling trips on the fly due to manpower shortages. The LTA wants to place their hopes on buses as a temporary band-aid measure to buy them time before more rail lines can open in a far-fetched future, and has invested much towards the $900 million BCEP too. It will struggle to work out against time-conscious Singaporeans who don’t want to play guessing games during their daily commutes.

This is a call to strengthen maintenance, not just on core mobility components in our public transport such as buses and trains. Auxillary support systems that build toward the overall public transport experience, such as live arrival timings, are equally deserving of good upkeep to ensure that they can accurately and reliably support riders in making informed travel decisions. Knowing when buses and trains are arriving gives riders a sense of agency over their journeys, which is an integral part of encouraging more to use public transport, and encouraging existing riders to stay on board too!

The cause of the Datamall glitch over the past month was attributed to data overwrite issues caused by build-up of cache in the system. Anyone reasonably knowledgeable about computer systems would know that memory caches need to be cleared out periodically to prevent overflow and system crashes. In simpler lingo, ever heard of that meme of 200 tabs open on Google Chrome slowing it to a crawl and eventually crashing the browser? A similar principle on a larger scale is at work here with the bus arrival data and the Datamall servers that host them. For something as complex as the LTA Datamall to be brought to its knees over uncleared memory cache, it seems to imply that the system was not periodically inspected and maintained to ensure optimum performance. And with the talent LTA hires for data computing prowess, this is a shockingly amateur mistake to make. Shouldn’t old cache be automatically cleared out anyway, in advanced, enterprise-level computing systems?

In an increasingly connected age, both on the ground and on the cloud, it’s only fair that riders of our public transport know when their buses and trains are coming, so as to give them assurance of a reliable journey. Having functional trackers (for BOTH bus and rail!) is an essential part of meeting these demands in a new age characterised by smart data-driven management and IoT. Failing which, the legacy fallback, though incredibly clunky, would be to provide timetables as a written assurance of bus service. If neither can be reasonably achieved for some reason, the last resort is to run service frequently enough such that riders are assured that a bus or train is coming soon enough to not significantly impact their travel time!

The comical situation today, particularly with the buses, is that none of the above are happening!

At least, let’s hope the second-generation onboard equipment that’s slowly rolling out now will improve the situation, and reduce the occurrences of “ghost buses” happening. But even the most advanced technology requires a robust maintenance regime to back it up against wear and tear over time, including in its digital forms. We learned this lesson with repeated MRT breakdowns over the past 15 years. Why shouldn’t it carry over to the many other systems that go towards forming our overall public transport system too?

Interested in building a better future for Singapore’s transport? Join the STC community on Discord today!

Leave a comment