By now, a majority of those interested in local transportation affairs would have heard of our Transport Minister Jeffrey Siow attesting that more, and longer, planned track & tunnel closures need to take place to ensure our rail system is viable for the long term. As the first of these service changes – a reduction in frequencies along the Circle Line – starts today, we must reflect on how to mitigate the impacts of these inevitable closures, giving rise to new ideas that ensure sustainability in our network, to mitigate further wear and tear, and allow restoration of the network.

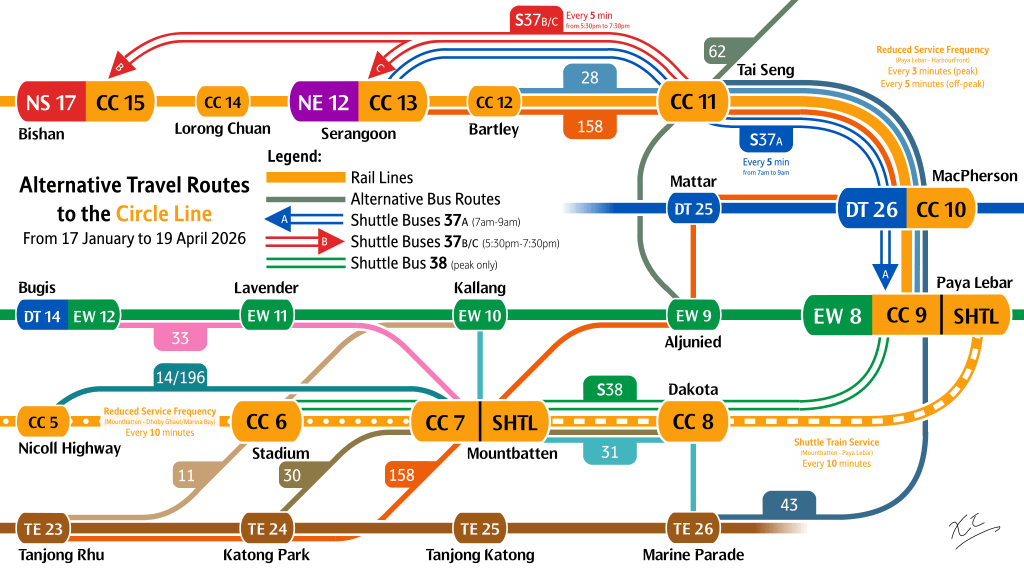

This year, to complement the 33% reduction in CCL capacity (from 27930 to 18620 passengers per direction per hour from Paya Lebar to HarbourFront), LTA has introduced shuttle bus services to complement travel patterns that see higher demand during peak hours. All 3 services (37A, 37B, 37C) in the Shuttle 37 series serve Tai Seng, a major employment hub. This is in tandem with Shuttle 38, serving the most affected stretch in Paya Lebar to Stadium.

Due to the lack of access penalty entering the transport network, as well as less concern for (perceived) speed in favour of comfort (in skirting the crowds) going home for the evening peak, workers located at Tai Seng will likely patronise Shuttles 37B & 37C more than Shuttle 37A, which operates in the morning peak from Serangoon, requiring NEL commuters to surface for the bus. However, those living in further-out towns along the NSL & NEL (Sembawang, Yishun, Sengkang & Punggol) may still choose to change to an MRT line to reach their destination – a behaviour implicitly encouraged by LTA. Shuttle 37C does this by offloading its NSL-bound passengers outside Bishan Station, rather than opposite it, where northbound buses call at – this is despite 37C needing to take a longer route, likely via Ang Mo Kio Avenue 1, instead of using a faster Outer Ring Road System (of importance later). While Shuttle 37B takes a more optimal route to Serangoon MRT Exit A, the bus stop there broadly has services that do not point northbound to the farther out towns either.

The rail network, with its higher capacity & faster speeds, is currently the backbone of our journeys. Promoted as such since its first stretch opened nearly 40 years back, the MRT has become embedded into our lifestyle – its monocentric system to this day promotes the Central Business District as the prime place for employment & leisure alike. Generally, it does well at this job; a 30-40 minute train ride from heartland town center stations to the CBD generally incurs only about 1.5 times the travel time as a direct car ride. (cite source in footnotes) However, our current system can rightfully be branded as a monocentric “commuter rail”, focusing mainly on the CBD, or forcing people onto the overcrowded CCL.

Bridging corridors or reaching areas far out from the MRT highly relies on:

- Taking windy routes around the MRT network, either crushing onto the Circle Line or diverting through the CBD. From Bedok Food City to Yishun Avenue 4, one would take service 17 to Bedok Interchange, either changing trains at City Hall, or Paya Lebar & Bishan via the CCL. At Yishun, they would negotiate the notorious walk to Yishun ITH and waiting for 805 or 812. This journey takes approximately 1 hour 40 minutes, compared to just 32 minutes by car.

- Taking a bus that does not reach their destination directly, where their route has to wind extensively. Despite Senoko Estate being a 30-minute drive away from Compassvale by way of Admiralty West Drive already pointing southeast, about 1 hour and 10 minutes is required via services 161 & 169 via further west Woodlands interchange.

This chasm between public transport & private transport thus makes Singapore’s preference for the latter unsurprising. In a survey we conducted last year, nearly half the respondents have indicated their preference to own a car if they had the means. This sentiment is echoed nationwide; cars are viewed as a status symbol, as it grants people more freedom to go to locations they desire, expanding their reach and quality of life. In our dense, interconnected city, bridging the gaps between our towns is important in revitalising the commercial spaces, industrial estates, and office spaces, making them more competitive and desirable. Among 2 in 3 Singapore residents who rely on our network to ferry them to places, how well-connected a place influences where they spend their money, or where corporations are willing to set up shop in return for better hiring. This is especially true in Changi Business Park, set up in the far east of the island next to Changi Airport, which has seen a steady decline in recent years – in part due to its location far out east, and in relative isolation from the rest of the island. Indeed, the MRT does work well in chaining together towns with the city, but decentralisation efforts may need further efforts.

This brings us back to the Circle Line, which generates two of Singapore’s most notoriously crowded interchange stations in Serangoon & Bishan, end-points of Shuttles 37B & 37C respectively. The Circle Line is a victim of its own success, and of our increasing reliance on the MRT network as a whole. Speed should not wait for the demand, or feasibility studies, to warrant building an MRT line. Some commutes can be covered by a traffic-prioritised rapid or fast-forward bus system, especially those closer to main road arteries. Tai Seng is one such example; located along Upper Paya Lebar Road, it is 1 turn away from Fernvale, and 2 from Yishun Dam, by proxy of Yio Chu Kang Road and CTE respectively. Using the corridors cars excel and beat buses at is the key to remaining competitive, and serving the people. Latching onto the hub-and-spoke demand along more corridors, and optimising especially its central leg through traffic priority measures, would thus make the commute more time-competitive, as a collection of buses within reach of residences, workplaces & schools can bring everyone closer to each other.

It is for this reason I propose services 43F and 701, a fusion of local sectors prioritising areas in the North-East further out from the MRT system, as well as the industrial center of Tai Seng. Rapid sectors will ensure speed increases, a larger catchment a transfer away from higher-quality service, and CCL relief during these works. Attached is a link to the routes.

- 43F is a rapid variant of 43, enabling faster connections between the North-East & South-East. 43 harnesses the Punggol Road corridor, briefly facilitating transfers along Hougang Avenue 3, and funnelling the North-East to Tai Seng, Paya Lebar, & schools along Marine Parade. While some of its structure is similar to 43e, 43F is slated to be full-day, and can sustain itself with its EWL connection & its relay link from Paya Lebar to Marine Parade.

- 701 links Punggol Coast ITH & Punggol Digital District directly to our second commercial airport in Seletar, before serving its main local catchment in Fernvale. A rapid sector along Yio Chu Kang Road chains Fernvale to Tai Seng. Paya Lebar & Stadium (on event days) follow, before chaining to the traditional CBD. North-Eastern CBD workers may expect increased convenience as they no longer need to surface at Dhoby Ghaut or negotiate space on the North-South Line. 701 terminates at Shenton Way Terminal, with provisions to serve residences & community hubs in the Greater Southern Waterfront. On nights and weekends, 701M penetrates the Suntec area.

Aside from relieving the CCL (and the NEL), other lines can and should be considered for such relief efforts, by targeting areas not served directly by the MRT. The map above also offers a cursory glance at 4 more potential services that can complement the MRT, providing a preview into the island’s overall connectivity. In fact, the example commutes shown earlier can each benefit from one of the new services shown above!

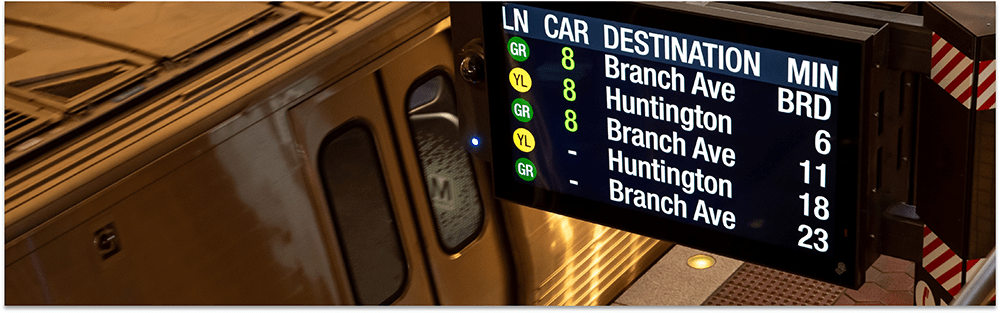

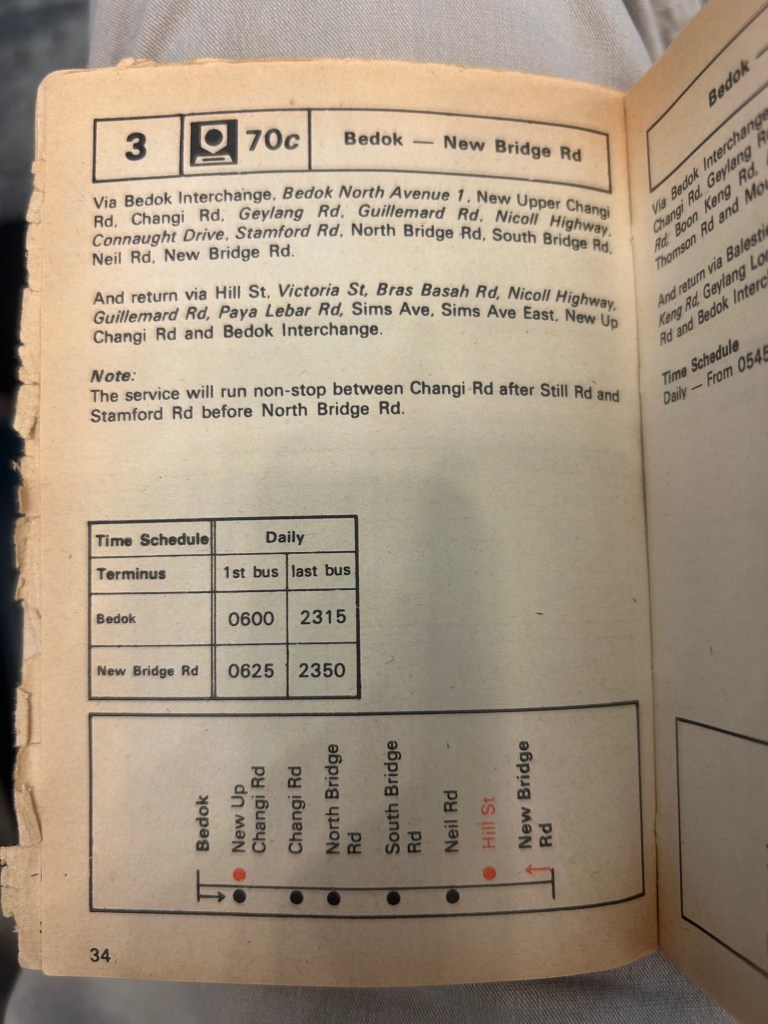

This brand of bus planning may be seen as novel, but it has actually been seen before. Internationally, the Superloop bus in London is well-known – it has 7 routes to carry passengers across arteries & corridors further away from the city center, and 4 radial routes direct between business & commercial areas and residences. The 7 circumferential routes, alongside the “Bakerloop” service, lean into rapid-stopping patterns to substitute gaps in the rail network. What is less well-known is our similar experiments with such buses – in the 1980s, before the EWL had been built, it was common for buses between Bedok & the CBD to skip large segments of Changi Road & Sims Avenue, in order to optimise for speed.

RapidBus 700 is a scheme that has gotten more attention, especially among bus enthusiasts, and implemented bus priority schemes between Woodlands, Bukit Panjang, Orchard & Shenton Way. A scheme that lasted from 1998 to 1999, buses deployed on 700 used to have transponders that turned red lights green at traffic junctions were the bus to miss the green wave optimised for cars. The trial did not succeed in replicating rail, and buses on 700 had their transponders removed, and the route was cut back in 1999 to ply a Bukit Panjang – Shenton Way route. The (apparent) absence of bus-only lanes along its route may likely have hindered its speed, and made 700 less time-competitive to other options at the time, despite its primacy to DTL2 by about 16 years.

In fact, current rail-complementary bus schemes have also seen some setbacks that has limited its patronage. Services like 660/M have, according to anecdotes, seen popular demand, in part because it serves Hougang West & Serangoon North, those same catchments 701 would leverage the lack of MRT connection in. However, those with catchments closer to the MRT, like 678, have seen limited success in becoming a competitive alternative, even as they offer doorstep connections to both home and office. These City Directs may be marred by traffic along the expressways, which can easily be caused in high traffic loads especially when vehicles slow down to merge or switch lanes, or in the event of rain. This thus shifts demand to the MRT, which funnels passengers to the town centers. In reinforcing the hub-and-spoke model that encourages transfers, and sometimes detours, the driver once again wins against the commuter.

Bus-only lanes along road corridors should thus be highly encouraged along the central sections of rapid services, occupying the leftmost lanes of the roads & expressways they ply on. To prevent further conflict with left-turning traffic, such left-turning traffic can enter the bus-only lane around 150m before the left turn. This deconflict would thus ensure a lower “stopping time to moving time” ratio, currently calculated at around 50% for most Singapore buses. In addition, no new space will need to be created – although private transport will be disincentivised, as it would have lesser capacity on the roads. For routes like 67 (on the map) or 129 currently, the flyovers they use may still need bus-only lanes for sustained fast travel. The movement of cars across the bus-only lanes can still be signalised, disallowing movement across the bus lanes for a short while to ensure continuous fast travel.

Using the bus to fortify gaps in our current MRT network, we can help increase competition between public & private transport, ensuring a more sustainable way to commute, even in the midst of planned rail work like on the Circle Line this year, or unplanned incidents like the September 2024 derailment. The humble bus can facilitate commute patterns requiring less capacity, or act as a temporary substitute for future MRT lines when demand is still lower – we just have to learn how to harness its power.

Leave a comment