Cover: Buses photographed on long feeder services 79 and 201 at Teban Gardens.

Imagine a bus route going right up to your doorstep, that offered you connectivity beyond your nearest MRT station or town center. By staying on the bus for longer, or taking it the other way from home, you could access another MRT station on a different line, a key corridor with lots of other buses headed to various destinations, or other amenities scattered around your town and the next. Yet these do not quite fit the definition of trunk services in the academic sense — they do not quite possess the island-spanning length, and a good many of these spend more time than desirable making detours to maximise catchment in housing estates or popular local amenities.

Despite being officially labelled as “trunks” in LTA lexicon due to the absence of the feeder label, one can unmistakenly sense the stark differences they have from other appropriately-labelled trunk routes. In their state of limbo between the trunk-feeder dichotomy, hides a great potential not adequately unlocked, despite their significant presence in our public transport networks.

For those who have stuck around on this publication for many years, you may remember frequent references to a route type known as “long feeders”, distinguished from conventional feeder services by bring anchored to multiple transport nodes rather than just one, and commonly classified under the trunk branding officially. Whilst this term has been used for at least four years on this site, its usage hasn’t caught on more (against hopes and expectations) in the wider community, despite there being some form of recognition that shorter trunk-branded routes are significantly different in character from their island-spanning long-haul counterparts. This post, due perhaps a few years ago, aims to set the record straight around the most misunderstood, and arguably underrated group of bus routes in Singapore.

Back to definitions

The term “long feeder” used to describe shorter trunk-branded routes is formed from its two key characteristics. “Feeder” in the name describes the nature of most trips made along such routes — typically fulfilling short-haul, last-mile trips linking jobs, homes and other amenities to major transport nodes, akin to the role feeders play in a traditional hub-and-spoke model. As explained in a post last year, this also builds towards the pattern of cyclical demand cycles characteristic of long feeders, which stand in contrast to typical cumulative ridership profiles.

The “long” part of the name is where they are distinguished from regular feeders — on a literal sense, long feeder services are generally always longer than their corresponding feeder counterparts in length. However, long feeders aren’t “longer” just for the sake of such — their key defining characteristic that sets them apart from the feeders everyone is familiar with is their connection to two or more transport nodes, instead of just one seen on conventional feeder routes.

An easy way to visualise this process would simply be to imagine the extension of an existing feeder route from its looping end towards the next nearest major node, thus providing a (usually) coverage-oriented link from one node to the next, rather than simply funnelling passengers towards one node only. As you will see later, this was indeed also how many long feeders in Singapore came to be.

A hidden treasure

Long feeder routes are immensely powerful, and even more so than the typically-classified trunk and feeder route type dichotomy commonly used in official terminology. While clearly not a substitute for the straight arterial trunk routes that move massive numbers of people across long distances, long feeders serve as the strongest complement to a robust trunk network in a public transport system. Despite their name that sets them apart from regular feeder routes, long feeders ironically perform the role of feeder services better than regular feeders themselves! Let me explain, with a simple numbers exercise.

Suppose we have a residential estate situated somewhere in between two MRT stations (we assume equidistance, although proximity and connectivity from each respective station are also factors for consideration in real-world situations), relying on a single particular bus route to bring them to the rail network. With a relatively comprehensive rail network in place, the specific choice of station used to access the rail network matters less, and this is particularly important in how long feeders work their magic in the bus network. That being said, the key ingredient possessed by long feeder services is their connectivity to multiple transport nodes, which is equally represented even in systems where rail is less expansive or developed.

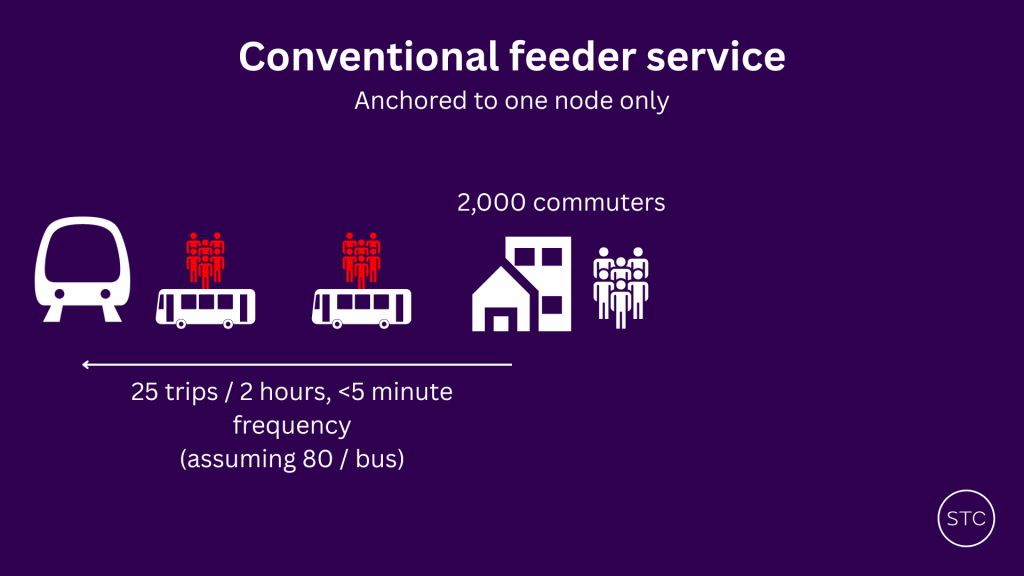

A typical peak period spans about two hours, which is the time period in which the rush hour crowd aims to travel from their homes to access the rail network (in the typical Singaporean commuter profile) on their way to work and school. Suppose we have 2,000 people relying on a singular bus route to access the MRT, some way or another.

In the case of a typical feeder service, which is only anchored to the rail network at one node, all 2,000 passengers must be funnelled in the same direction to the sole node upon which the feeder is based out of. This translates to a total of 25 trips that must be operated, assuming each bus has a capacity of 80 people. We assume, of course, that we are just providing enough capacity to barely fit everyone, running each bus at crush loading. In real life, bus operators tend to aim for higher service levels than that, but the point still stands.

That’s one bus every less than 5 minutes, which will put it ahead of bus services such as 190, 235, 371 and 858 in the frequency game, all while having each bus packed to maximum capacity. At 4.8 minutes, your feeder service joins the league of super-frequent feeder routes in Singapore that are such out of sheer necessity due to the inability to design more efficient routes, such as 241/A, 300 and 807.

It also means, that for the deluge of buses one spams on this feeder route, that all of the equally many buses would be running the return trip from the MRT station more or less completely empty. That’s some wonderful resource utilisation right there, and so much for wanting to reduce wastage in bus operations.

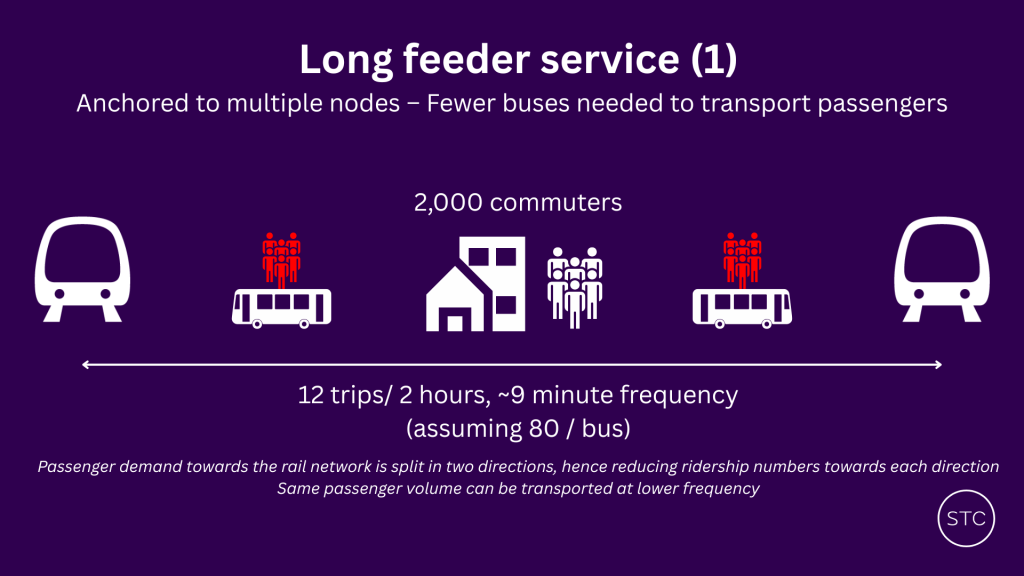

Now suppose that a long feeder route exists to connect this residential estate, to not one but two (or potentially more) different MRT stations. From here, the situation can evolve in two directions. The first, is the paradoxical axiom that long feeders require fewer resources to serve the same number of passengers as regular feeders do. Take the same group of 2000 people trying to access the MRT again. With a long feeder serving them in place of a regular feeder, this crowd is split in two directions, with both enabling access to the rail network. Logically, what follows is a reduced need for capacity per direction, where because both directions of travel can be served in a single trip, only half as many trips are needed to serve the same ridership (from a pure theoretical basis).

At the same maximum occupancy level assumed in the above scenario, a long feeder permits lower operating frequency to maintain service quantity to a given catchment area, with ridership split in both directions. Hence, fewer trips are needed to meet demand, in turn reducing fleet requirements for bus services. What would have been a feeder running every 4-5 minutes out of necessity could be a more reasonable long feeder service operating every 8-10 minutes during peak hours, further removed from the reliability problems arising from running hyperfrequent bus routes.

In the modelled simulation above, this translates to about 12 trips per direction instead of the original 25 across the two-hour peak period span, which corresponds to a headway slightly shorter than 10 minutes. Definitely more workable, and less prone to bunching than what was originally a hyper-frequent arrangement with buses already pressed very close to each other.

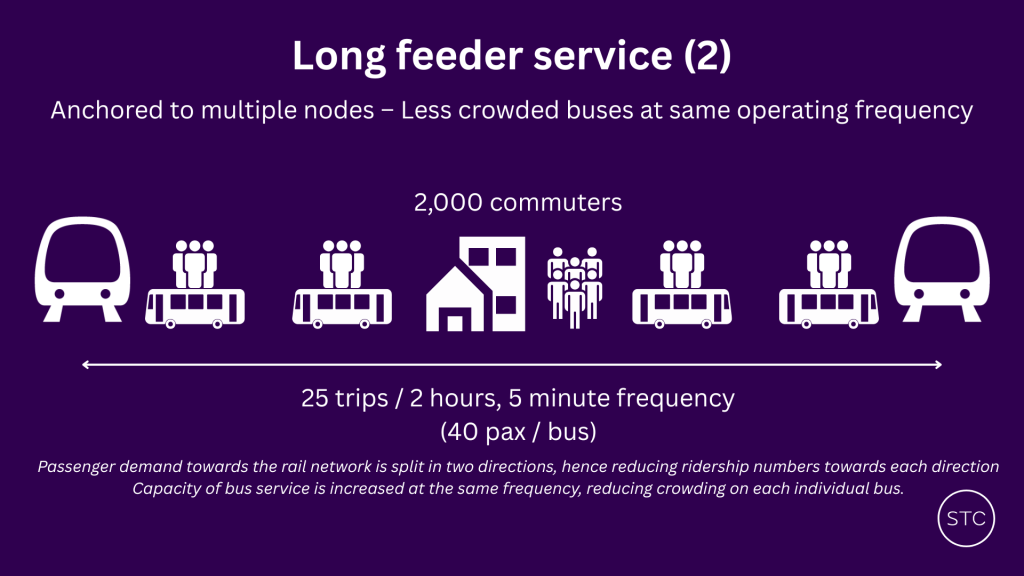

This can swing the other way too. Instead of having to bear with crush-loaded buses, converting a feeder service to a corresponding long feeder is capable of reducing crowding on individual buses, when run at the same frequency as the original feeder. In the same situation as above, that means that with 25 trips running per direction, each bus should only be carrying about 40 passengers, with more than ample space to make one comfortable even on a relatively short first-mile bus ride.

This also comes with the added advantage of much less wastage incurred, as buses will be loaded in both directions on long feeder services, as opposed to running mostly empty on conventional feeders, in both situations.

Of course, in real-life situations involving long feeders, a mix of both advantages are enjoyed, with the combination determined by specific conditions on each route. Rather than swinging to one extreme end when it comes to the crowd mitigating ability of long feeder services, most long feeders in Singapore adopt a mixed operational approach, operating somewhat less frequently than their feeder counterparts to save resources, while still maintaining some form of headway baseline to reduce crowding on buses. (That last statement comes with a big catch, which we’ll get to later.)

This has an implication on the fleet choices for long feeders: in most cases, the most suitable vehicle type for long feeder services, especially when faced with high cyclical demand from stringing together many residential / industrial areas and transport nodes is the bendy bus, where more doors (particularly when coupled with all-door boarding) enables long feeder routes to better handle high passenger exchanges than the mainstream fleet choice of double-decker buses. This includes the 3-door variants introduced in 2021 and expected to be further promoted in coming years with more procured this year. Counterintuitively, given the surprisingly long length of some feeder routes, it might be more appropriate to deploy double-deck buses on some of them instead of current bendy deployments, which could be diverted to long feeders in greater need of them! A strong point for the re-introduction of a large bendy bus fleet would be to optimise operations on the many well-used long feeder services around Singapore, particularly during their respective peak loading periods. Today, only two services with long feeder characteristics (184 and 807) regularly receive bendy bus deployments, with one more such service incorporating a long feeder segment for part of its route (858), due to the small number of bendy buses that remain on our roads.

The mass usage of double-deck buses on high-demand long feeder routes, where passengers routinely bottleneck around the staircase area around the second door, is a major cause of delays en-route, which significantly impact the reliability of long feeder services heavily relied on by residents and workers alike. This builds towards a rather bizarre counterpoint against the long feeder route type, which will be covered below.

From where do you come from?

Note from author: Mentions of bus services in the following section of the article are hyperlinked to a map of the route, or a resource indicating the route alignment in question, for readers unfamiliar with the routes mentioned. Please click on the link to view the respective bus route.

In the Singapore context, with the bus network having gone through multiple series of heavy revisions in the past five decades, the long feeder has found itself evolving from the cracks of legacy networks being torn up and re-stitched together with changing tides in bus planning. Due to the unofficial nature of the long feeder designation, many different paths of emergence exist when it comes to the formation of long feeder services. Excepting purpose-built long feeders mostly introduced during the Bus Service Enhancement Programme between 2012 and 2017, there are four main ways in which long feeders have been formed:

Shadows of former selves

From the perspective of a 2020s observer, it may be difficult to establish that a currently-existing long feeder service was once part of a far longer route that extended significantly beyond its current scope. If one digs the archives sufficiently, quite a number of long feeder services today trace their origin to the long and unwieldy long-haul trunk bus services characteristic of the 1970s and 1980s. As the bus network was progressively reformed with post-nationalisation reorganisations and the introduction of the MRT, many of these routes were shortened to reduce duplication with other trunk bus services, thus making them more manageable to operate and navigate.

With the growth of the network, many of these now-separated branches of former long trunk routes became long feeder connections linking further-away communities to main bus corridors and MRT lines, with a transfer required to continue down the main trunk route.

Today, service 73 is a long feeder linking the residential estates of Serangoon North and Serangoon Gardens to the North-South Line at Ang Mo Kio and Toa Payoh. It was first introduced in 1971 between the Yio Chu Kang and Tanjong Pagar (corresponding to today’s Shenton Way) bus terminals. Like many other bus services of its time, it heavily duplicated a massive braid of many other similar routes out of the downtown core, before splitting off to each respective branch in the heartlands. No records exist of its precise route back then, but one could imagine it as a sort of variant route to the present-day services 167 and 162 (prior to the 2023 cut), splitting off at the Jalan Toa Payoh junction (today’s PIE flyover) to access Toa Payoh and Serangoon Gardens.

By 1974, in line with rationalisation efforts by SBS after consolidating all the nation’s buses, 73 was cut back to end at Toa Payoh, with the sector into downtown being integrated with routes that probably mirror the present-day 57 and (pre-2023) 162. Further adjustments in the subsequent decades also resulted in the route being shortened again to start from Ang Mo Kio, with the old sectors transferred to new trunk routes that roughly correspond to the present-day Service 70 (Yio Chu Kang – Shenton Way).

Prior to the opening of the North-East Line in 2003, service 82 used to ply a route that mirrored the full length of the NEL, from Punggol Road End to Shenton Way. The NEL’s opening in 2003, where SBS deemed it financially unviable to continue operating parallel bus services to the NEL, saw 82 getting shortened to connect to the NEL at Serangoon, with the sectors paralleling the NEL alignment (between Serangoon and Farrer Park, with the remaining segment to Shenton Way absorbed into the present-day Service 107) cut off. Today, all that remains of the 82 that once spanned the entire NEL is its unique segment along Punggol Road, a long feeder linking residents to the Punggol, Hougang and Kovan NEL stations.

An example fresher in recent memory is perhaps Service 66, which was shortened as part of DTL3 service cuts in 2021. Formerly a long-haul trunk service between Jurong East and Bedok, much of the route was axed due to duplication with the routes of services 65 and 67 (on the pretext of “DTL3 rationalisation”), leaving its unique stub sector linking western Bukit Batok estate to key transport nodes in Beauty World and Jurong East.

While not the full picture, many long feeders were the historical product of key events in Singapore’s bus planning history such as the 1973 merger, the MRT Initial System Rationalisations (1988-1991) and TransitLink Network Integration Exercise (1991-1993) which birthed most of the present-day bus network, as well as more recent rail rationalisation exercises. For the better, with many of these long feeders playing a highly valuable role in giving residents more choice of destinations, all while serving them more efficiently than traditional feeder services are able to.

Trenchcoating

Some long feeder services are affectionately referred to in the STC community as “trenchcoat” services, in reference to the meme of three children disguising themselves in a trenchcoat to pass off as a singular adult. For good reason too — the next most common origin of long feeders in the Singapore bus network is their formation through merger of multiple feeder routes. In the case of some, their present-day routes are still marked by the legacy of their past as multiple disjoint feeder routes too, with certain segments operating one-way (or duplicated) to maintain the coverage provided by its constituent feeders.

Across the 1990s and early 2000s, selected feeders, particularly in eastern and northeastern Singapore, were merged to form long feeder routes that remain well-known to this day. Granted, there was a profit motive involved as SBS sought to eliminate feeder fares through merging them into trunk-branded long feeder services, but these were the first instances of what is also known as feeder integration. It’s a fascinating topic that’s best left for another time.

Service 3, today a long feeder linking Punggol to Tampines via a detour in Pasir Ris, was the product of a merger between Tampines feeder 294 and Pasir Ris dual-loop feeder 357, and is a key route providing doorstep connectivity to many residents who would otherwise be isolated from the larger core bus network without a mandatory connection at the respective town centers. Traces of its past are still visible today — 3 plies two different one-way segments along Tampines St 21, the legacy of the former feeder 294’s one-way loop.

Over in Hougang, a massive reorganisation of legacy feeder services had to be conducted in line with the town’s center of gravity shifting north. Prior to the opening of the North-East Line in 2003, the main transport node in the Hougang area was the defunct Hougang South Interchange, located beside the present-day Kovan MRT and hawker center, and many legacy feeder services originated from there, instead of the present-day hub at Hougang Central. In April 2004, the full migration of the Hougang South interchange to the present Hougang Central site resulted in the remaining feeder services located there to be integrated into long feeder services 112 and 113, in turn connecting it to the new Hougang interchange too.

Today, the unique layout of services 112 and 113 enable passengers to access more amenities across both the old and new portions of Hougang town, including various markets (one of which the old Hougang South interchange served directly), malls, schools, residential estates, and (in the case of 112) industrial estates. These connections extend far beyond the scope of what the former feeder services (and their current feeder counterparts in Hougang) are capable of achieving, whilst also providing unique connections for passengers otherwise not possible with other routes.

Promoted in rank

A much more recent trend compared to the rest, some long feeders have also been formed through extending feeder routes to the next nearest node, as part of enhancing connectivity by bridging gaps left by legacy single-node feeder arrangements. This mostly happens with new towns, where new residential estates, amenities and transport nodes are added significantly later than existing infrastructure available, necessitating the extension of existing feeders to meet demand.

Since Tengah is in the spotlight currently when it comes to issues around urban planning, municipal management and transport operations, (and also because the current Transport Minister’s ward includes it), it’s worth mentioning their principal bus service, a product of extending a former feeder service. In September 2023, feeder 944 was extended into the Tengah estate for the first time, and renumbered as “trunk” service 992. A further extension to the new Tengah interchange in July 2024 formally upgraded its status from a Bukit Batok feeder to a long feeder linking the (currently-isolated) Tengah and Bukit Batok nodes. With the opening of the Jurong Region Line in 2027, this long feeder characteristic will be cemented in 992’s demand patterns too, resolving existing overcrowding issues on 992 caused by overwhelmingly unidirectional travel demand due to a lack of a rail connection on the Tengah end currently.

A more mature case study is that of Service 901M, which links residents in Woodlands South to the Woodlands and Admiralty stations on the NSL. Introduced in 2019 as an extended variant to feeder 901, it bridges over a critical gap in the bus network of southern Woodlands, where key civic amenities (Woodlands Galaxy Community Club, Kampong Admiralty etc) remain out of reach for residents near Woodlands South station. 901M is also a rare case of a long feeder to be branded as a feeder service (instead of the usual trunk) due to the way town boundaries are defined in bus planning.

Same route, different type

The last method by which long feeders form is much less intuitive than the rest, as it involves no change to the route itself. A small group of long feeder services came about as a result of changes to the larger surrounding transport network, rather than to the route itself. Recall that long feeders are distinguished from their conventional feeders by being anchored to two key nodes in the transport network rather than just one. The addition of a new node near the outer end of a feeder service can be a catalyst for a route to take on a profile more akin to that of a long feeder, by encouraging bidirectional travel demand patterns that are part of the operational efficiency that define long feeder services.

We turn our attention to service 150, an otherwise unassuming circulator service linking the estates of Telok Kurau and Marine Terrace to Eunos station along the East-West Line. Initially conceived as a low-frequency direct feeder connection for residents of Marine Terrace and Telok Kurau (who otherwise faced a significant access penalty transferring to the EWL from services 13 and/or 15) during the BSEP in 2016, the opening of the Thomson-East Coast Line’s fourth stage in June 2024 opened up a new point of access to the rail network at the looping end of 150, transforming its character from a purely unidirectional demand pattern towards the EWL to a more mixed demand balance to both the EWL and TEL. More access options now exist for those heading towards Parkway East Hospital, or the inner Marine Terrace estate, with its elevated status as a long feeder service providing more connectivity than before, all without having its route changed in the slightest!

Fitting every need

Here’s the very neat part about long feeder services in bus planning. They have a place in almost any type of network, regardless of the predominant planning ideology in place. In fact, the above-outlined characteristics of long feeders make it such that they’re compatible with almost all bus planning doctrines out there. Have a keen interest in conserving operational resources due to acute shortages on the market? Long feeders operate more efficiently than their corresponding feeder routes and transport more passengers with fewer resources. Interested in vastly expanding access? Long feeders offer more connection options than their feeder counterparts too! Heck, even if you’re the extreme NUMTOT kind who thinks the very existence of buses is a negative externality to be eradicated in favour of rail-based transport, long feeders are also your best friend — the inevitable coverage dead zone of the rail network can be effectively served with the fewest buses using a handful of long feeder routes anchored to existing nodes on the rail network, whilst you’re waiting out your fantasy of rail to every corner of the city.

In the connective grid network, the long feeder plays two major roles — to provide direct, convenient connections across intersecting network elements that might otherwise have required a transfer, and to provide coverage to areas where the road network does not sensibly permit the insertion of a main trunk route to pass through.

On hub-and-spoke networks, long feeders serve as amalgamations of feeder elements in the network, serving as useful last-mile connectivity, whilst giving residents more options to access various points of the rail network. Even in Singapore, where the hub-and-spoke model favouring feeder services has been widely promoted on an official planning level, long feeder services continue to do much of the last-mile heavylifting in places that fall through its cracks — towns not officially recognised by HDB, areas located between planning boundaries, and industrial / business clusters not recognised as worthy catchment for traditional feeder services. From the HDB estate of Serangoon North to the bungalows of Mount Sinai and factories in Sungei Kadut, long feeder services maintain vital last-mile connectivity to the outside world, where the feeder component of the hub-and-spoke model remains wistfully absent otherwise.

Common misconceptions

Because of how little long feeder services are acknowledged to be of a separate category from both standard trunk and feeder services, they’re a very misunderstood bunch too, with countless misconceptions abound surrounding their existence. If you made it to this part of the article, here’s where we clear up the confusion around these oft-misunderstood members of the bus network.

“Distance-displacement ratio”

By far the biggest misconception around long feeder services is the idea that such routes should be dismissed due to the supposedly many detours that take, and this belief is reinforced by the “squiggly” appearance of the routes of many long feeders on maps. In more formal words, it means that long feeders typically have a very high distance-to-displacement ratio (DDR), and correspondingly high end-to-end travel times. Complaints about “useless windy buses” are often targeted at many well-used long feeder routes, with ill-informed voices calling for their withdrawal, especially in cases where the long feeder links multiple MRT stations along the same rail line.

Commonly-cited examples of this phenomenon are services 49, 856 and 991, all of which are long feeders stringing multiple transport and community nodes together with vast residential or industrial areas, often taking very windy routes to connect them all. Among them, service 49 also has the highest (ie “worst”) DDR at 3.63 between Jurong East interchange and its looping point along Jurong West St 42.

Here’s the catch: This misconception is rooted in the idea that all bus routes are meant to be ridden end-to-end. More seasoned STC readers may know the falsehood of this belief, with cyclical and cumulative demand patterns forming two distinct types of ridership demographics on all public transport services. Contrary to the above mistaken belief, long feeders are not meant to be ridden end-to-end, but instead used in a manner more akin to last-mile connectivity, between destinations and nearby nodes. Whilst the overall route might look windy, the paths taken by long feeder riders are not — they would be equivalent to what a feeder services would have offered. Their windiness is not a bug, but a feature of the efficiency that defines long feeder services. At the core of long feeders’ immense usefulness, is their act of combining many overlapping short journeys on the same route. And if one pays these long feeders a visit during the peak hours, one might find that contrary to the belief espoused in the statement above, long feeders find themselves useful to a massive lot of people travelling between their homes, workplaces, and the core nodes we’ve established our transport networks around.

“Still a trunk service”

This is a particularly tricky argument to tackle, but like with most things in Singapore transport planning that involves naming semantics, you’re best off ignoring official designations if you want serious analysis of the network. It’s pretty obvious where long feeders deviate from trunk services — the latter are characterised by their long, (generally) straight routes, with longer, cumulative ridership patterns also being a typical trend. On the part of official planners, a lot of the waters are being muddled both deliberately and unintentionally by mixing long feeders and genuine trunk services under the same “trunk” designation, because the vastly differing conditions of both route types mean that different strategies — and operating standards, need to be applied for the corresponding route. This will be covered a bit later, regarding the inadequate service standards that highly useful long feeder routes are held to, due to structural reasons in our bus planning and management.

Note that there’s an additional real-life nuance that complicates this distinction slightly: some trunk (and even express!) services incorporate a segment at either or both ends that wind in comparatively minor road elements, similar to those seen in long feeder services. Examples include trunk services 28, 75, 168 and express 502. These are best described as trunk services incorporating long feeder elements, and in terms of the challenges posed in their operations, belong in a slightly different category from both standard trunk and long feeder routes.

“Not reliable”

Recently, a bizarre school of thought has emerged around the history of the long feeder’s emergence, claiming that long feeder routes are detrimental to bus reliability and “would never be accepted in today’s bus planning” due to “a need to hit service performance metrics”. Referencing the BSRF which bus services are benchmarked against in the BCM era, this belief asserts that long feeder routes are prone to bunching and negatively impact the welfare of bus captains, who supposedly drive much longer before being able to go on breaks. This is a highly loaded statement, with a lot of other conflated factors to unpack. Nevermind the fact that the literal first route introduced under the currently-ongoing BCEP (861) is a long feeder linking eastern Yishun to the Canberra and Khatib MRT stations, that is, which shows their continued relevance even today.

In a similar vein to those in the past who claimed long bus routes were inherently unreliable, this same argument falls victim to the same fallacy of assuming reliability independent of infrastructure available on the ground. Long feeders, by virtue of going through more traffic lights in smaller neighbourhood roads, are indeed at a disadvantage in terms of reliability assuming existing Singapore conditions, where a lack of measures to counteract the unpredictability of traffic signals and impact of congestion throw buses off schedule more often than desired. But this is the fault of the lack of bus priority in our road infrastructure, and not that of the route type itself.

Trunk bus services (or feeders, as they so claim!) are not any less prone to the same elements of uncertainty that long feeder routes face en-route, which are factors entirely unrelated to the route profile. Things like the lack of bus lanes, improper traffic signal sequencing, the use of archaic operation protocols in boarding (i.e. boarding from one door only, as opposed to the modern standard of boarding from all doors), are real factors that can severely impact a route’s reliability, and whose impacts are magnified the more frequent the route is. Service quality enhancements that work on main-trunk BRT-style bus services elsewhere, such as the implementation of all-door boarding and traffic signal priority for buses, should also be effective for long feeder routes, which utilise the same vehicles and general road infrastructure that the aforementioned bus enhancement projects have to work with.

Where they partially have a point, they fail to identify the crux of the issue, from which the misdirected criticism originates: most long feeders today, due to legacy SBST bus planning practices, operate as loop services as their shorter route length compared to full trunks made it more economical to only layover at one end to minimise downtime. Looping arrangements, even when the non-anchor end lies within a logical terminating point (eg a bus interchange, such as Toa Payoh for 73, 159 and 163 or Bedok for 60 and 69) compound other factors that negatively impact bus reliability, giving rise to the phenomenon of real-world long feeder services underperforming in commuters’ expectations.

In newer long feeder services, this issue is resolved through establishing long feeders as bidirectional services with scheduled layovers at both ends of the route despite their shorter nature. Tengah’s “signature” bus service 992, despite a total journey time of less than 30 minutes, lays over at both the Tengah and Bukit Batok termini, giving it ample time to recover from inevitable delays caused by high passenger loading in Bukit Batok West. In a similar vein, reforms in this direction are also being undertaken on legacy long feeders — 173, which used to immediately depart Clementi on arrival, now has a scheduled layover time there to improve reliability (and enhance bus captain welfare, per the recommendations of the bus safety committee convened earlier last year). Taken together, these are all realistic steps that can be taken towards ensuring reliable service on long feeder routes, disproving the notion of their inherent lack of such.

Underrated, and neglected

Unfortunately, in spite of all the compelling benefits offered by long feeder services in our bus network, the truth on the ground could not be more stark — rather than rising fully to their potential as the star players of the bus network (even within the confines of LTA’s hub-and-spoke planning framework), it is almost as if they are being deliberately singled out and sidelined as a group by design.

Mostly classified as full trunk services, long feeders are held to the same (lower) standards that trunk bus services are benchmarked by, despite their critical roles in ensuring last-mile connectivity for large numbers of people who live, work and play in the communities they serve. Despite moving volumes of passengers equivalent to or exceeding corresponding feeder services, most long feeders operate infrequently by last-mile transit standards, and are also accorded last priority by bus operators. Whereas BCM-era regulations stipulate that all feeders must not operate less frequently than 8 minutes during peak hours, the standards which long feeders are evaluated by follow the much laxer one imposed on trunks: 80% of which are to operate at 10-minute headway or better, with the rest operating no less frequently than 15 minutes during peak hours, with room for special exceptions (as seen in the cases of 167 and 852 in recent years — operating at consistent frequencies of 30 and 20 minutes throughout the day)

By current metrics, almost all long feeder services operate at “acceptable” quality, despite arriving almost twice as infrequently as their feeder counterparts with a larger ridership body to tackle. Issues pertaining to crowding and unsatisfactory wait times (the latter of which is compounded by existing reliability problems described earlier) are hence common on long feeder services, and not much is being actively done to remedy the situation as existing benchmarks deem these service levels sufficient. Bus operators are also not incentivised to improve service on long feeders as a result, and even resort to stealing buses from them first to plug service gaps on feeders when unforeseen circumstances arise. How extreme can this get, exactly? Long feeder 112, formed from the merger of legacy feeders in Hougang South (mentioned above), is a far cry from the feeders it replaced today. With abysmal scheduled frequencies to begin with due to lax standards enforced (because of its trunk classification), all it takes is a little bit of fleet diversion to other services SBS Transit deems more in need for buses, and a pinch of manpower shortage, for its frequency to nosedive to an eye-watering 40 minutes. Did the fact that it was the peak hour seem to bother operations managers a single bit? Seems not.

Stuck in limbo, it seems, for these group of bus services that are neither definitively a trunk nor feeder, but also appear to be a crossover of both, find themselves shouldering heavy responsibilities, but accorded none of the recognition they deserve, nor the respect they should command as the silent heroes of our public transport network. Neglected by bus operators and actively disparaged by higher planners, the long feeder deserves much better.

This next part is more subjective, so it’s been left for the last. As a personal observation, it seems like with a couple of exceptions here and there (new 3-door double-decker buses on 69, or electric bus deployments on 38, 40, 976 and 991), the fleet of Singapore’s long feeder bus services are generally kept in a much worse condition than the rest of the bus fleet assigned to feeder or trunk duties. Until the very recent (and still limited) proliferation of 3-door electric buses in the northeast and west, most long feeder services in Singapore sported the least well-kept members of their operators’ fleets — worn out, severely aged, and likely neglected even in back-end maintenance cycles too. There’s a well-understood need to keep buses in good condition for long-haul rides, as is the case for flooding long trunks with buses selected for good performance and comfort. Less acknowledged is the need to maintain a similarly decent ride quality when repeatedly moving large volumes of people across shorter distances.

I’m not asking for long feeders to be officially recognised as a separate route classification in public-facing administrative lexicon (although, it’d be really nice to) due to the very hazy boundaries distinguishing it from both traditional trunk and feeder route profiles. And in Singapore, there’s the compounding factor of a fare cap applied on feeder-branded bus services too. But there minimally needs to be an acknowledgement that long feeders possess unique characteristics that distinguish it from traditional route profile dichotomies established decades ago, and take these circumstances into account in the planning and operation of various bus services in our network. Ultimately, the best outcomes for the 70% that rely on public transport in Singapore is through maximising the potential of each element comprising the network, and sitting under our many long feeders nationwide is a vast untapped pool of potential abundant service to unlock. Half the reason why that is so, is because the highly limited range of operational vocabulary in use today erases their presence altogether, which is why this post aims to introduce and spotlight long feeder services.

What’s also interesting too, is how existing long feeder services can spearhead a major reform in our bus system to meet growing demand for public transport, in a time when existing resources are not expanding quickly enough to match it. Albeit, that’s better left for another time.

Interested in building a better future for Singapore’s transport? Join the STC community on Discord today!

Leave a comment