As the RTS Link (the one connecting Woodlands North to Bukit Chagar) nears its completion, and eventual 2026 opening date, our Malaysian friends are beginning to see the potential of improved cross-border connectivity. Earlier in July, Johor’s chief minister visited Singapore, where he met our top leadership and proposed strategic initiatives in line with furthering the realisation of the Johor-Singapore Special Economic Zone.

One of them, as reported, was a proposal to build a “second RTS link”, connecting the western parts of Johor and Singapore. No details were provided, but the chief minister suggested Iskandar Puteri and Tuas as potential termini for the new rail link.

On the cross-border trajectory

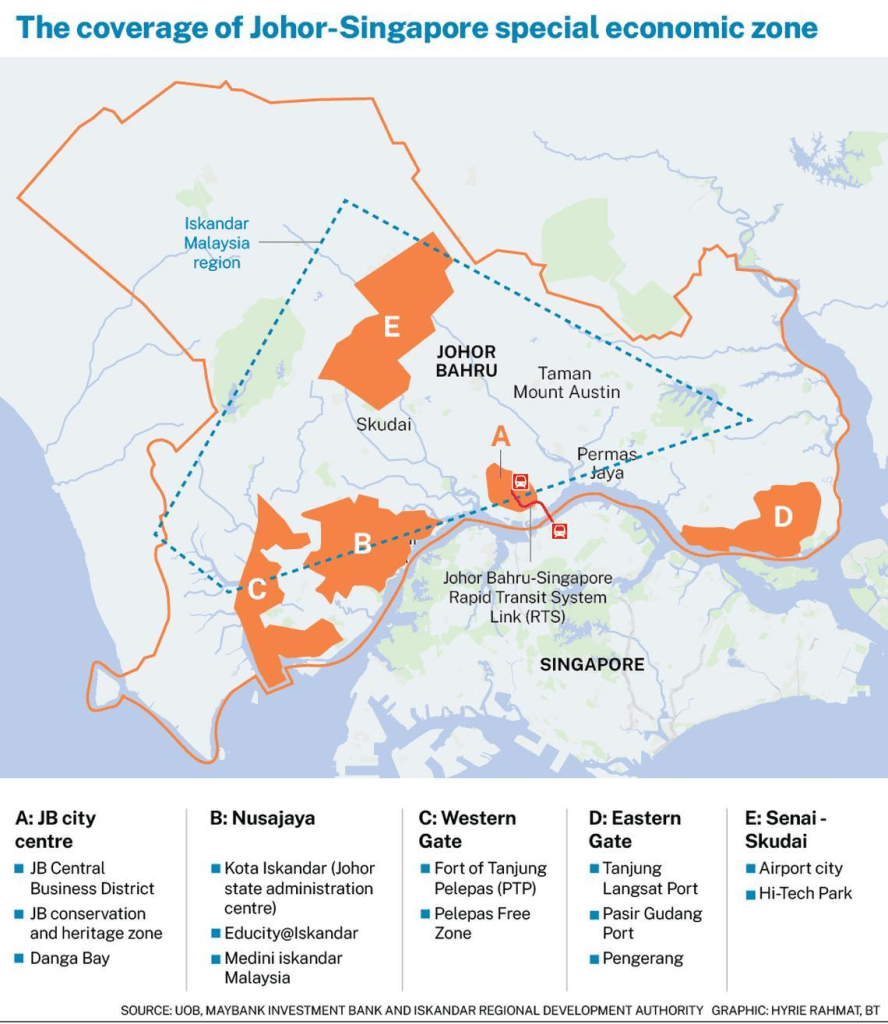

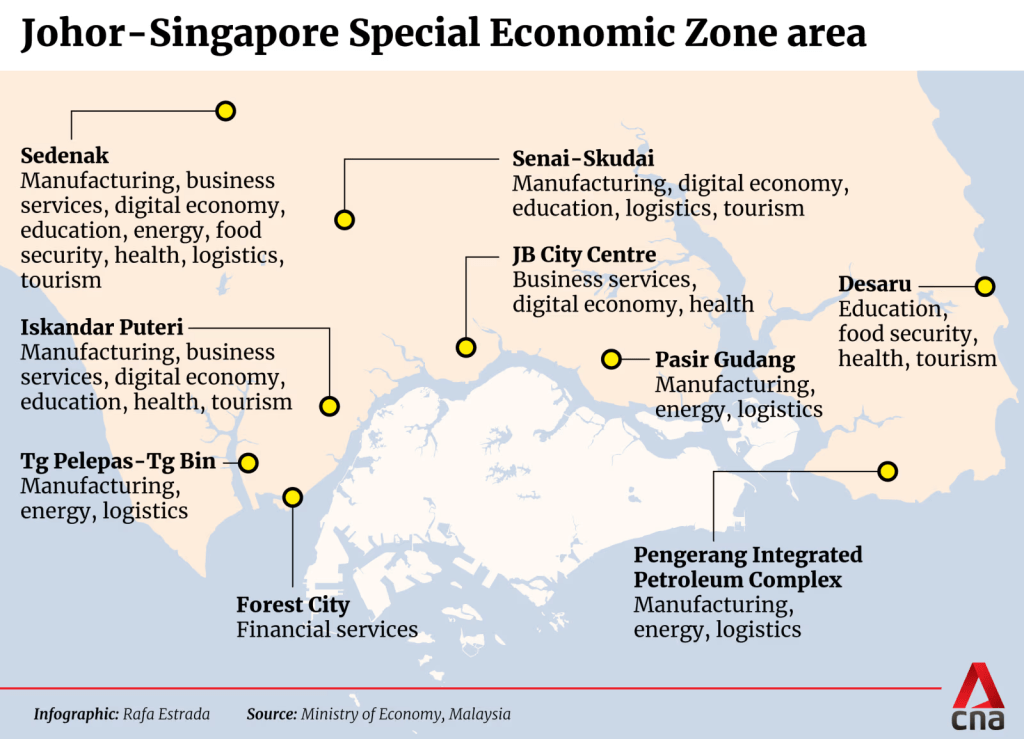

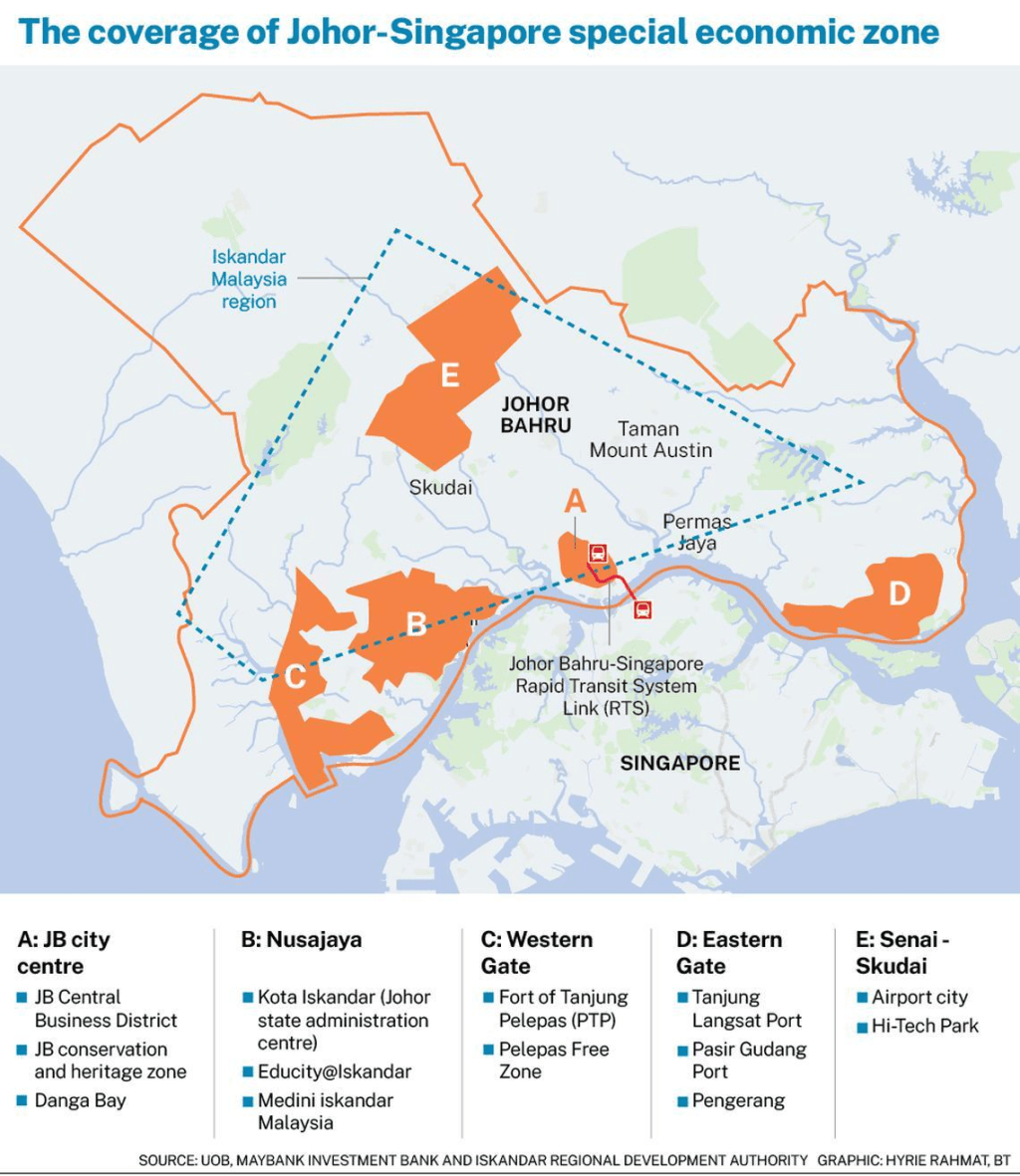

Let’s zoom out a bit. In January 2025, the leaders of Malaysia and Singapore announced the next step in furthering economic cooperation between both countries — the Johor-Singapore Special Economic Zone, or JS-SEZ for short. Intended as a free trade zone between Singapore and Johor, it’s expected to unlock the potential of both sides. With a combination of abundant human capital, Johor’s wealth of natural resources, and Singapore’s large capital stockpiles, removing barriers to business and trade across the border would unleash growth on both sides of the border beyond what was previously possible.

The JS-SEZ is significant for being one of the first instances of an urban megalopolis bring developed across a national border, with each side complementing the other. Similar upcoming efforts, such as attempts to further integrate Hong Kong with Shenzhen and the Pearl River Delta Greater Bay Area, will draw inspiration and information from the experience of the JS-SEZ. Previous amalgamations of cities into larger clusters, such as the creation of Greater Tokyo or the Jingjinji urban agglomeration, have almost entirely been within the borders of a singular nation.

It goes without saying, of course, that while removing barriers of access (including physical ones) to trade is half the battle won, the other half will be significantly tricker, considering the realities of urban transportation in Malaysia: building the connectivity needed to realise barrier-free access between the two countries both in name and in reality. As a preliminary first step, we have the RTS Link connecting Bukit Chagar in downtown Johor Bahru to Woodlands North, coming up next year.

An unmet need

Even today, cross-border travel for the many Malaysians working in Singapore (and vice versa) is no walk in the park. From the snaking lines of vehicles waiting to cross the border, to the overcrowded buses shuttling workers between Kranji and JB Sentral, and the shared experience of waking up at ungodly hours to prepare for the cross-border commute, few would tell you that the way they travel currently is by choice. The same story repeats itself with those travelling for leisure too — everyone’s sat in that same stifling traffic (our Team members included!) and spent hours wishing they were on either side of the border doing something fun or productive already.

Whilst cross-border travellers are largely resigned to the harsh reality of inadequate cross-border transport solutions, the demand for better cross-border connectivity continues to be expressed in various forms occasionally, Last month, Malaysia’s APAD (equivalent to our LTA) formally requested for LTA to consider bringing forward the operation hours of Singapore-based cross-border bus services to begin at 4am, instead of the current 5am, to complement fledging efforts by Malaysian cross-border bus operators to disperse early-morning peak crowds.

On the other hand, despite efforts by regulatory agencies on both sides of the border, illegal cross-border transport services enjoy steady demand on both sides of the border despite their illicit nature. The reason? Existing sanctioned transport options are unable to adequately meet their varied travel needs. Perhaps crowding on a Causeway Link bus at 5am may be a bearable grudge for a working-class adult travelling alone with nothing more than a backpack, a wallet and a phone. A family of four, with young children, three bulky pieces of luggage, and living a considerable distance from any legal cross-border transport pick-up points (eg. Queen Street, Kranji, Jurong East) would feel significantly differently on this matter. Illegal? They value the convenience and comfort that illegal ride-hailing services can offer.

And in a world where the large majority of the Singapore population is no longer clustered immediately around the civic area where Queen Street Terminal rose to prominence as a cross-border transport hub, there is little incentive for Singaporeans to want to detour downtown just for their JB getaway, even if they do not possess a car themselves. Neither for Malaysians too, whose employment is presently concentrated in the heartland areas far from the city. For the matter, the people of Johor live in a greatly spread-out area spanning the entire width of the state too — from Pontian in the west to Pengerang in the east, and they find JB Sentral a more appealing location to change for cross-border services than the estalished Larkin hub. As can be seen, the present status of only recognising Larkin and Queen Street as the sole proxies of cross-border travel is incredibly dated and archaic, a relic of when the map of “Singapore” only extended as far north as Rangoon Road.

Cross-border travellers are increasingly voting with their feet too, against the intended direction of the authorities to clamp down on these unlicensed services. Officially-sanctioned cross-border taxis, only permitted to operate between the Larkin and Queen Street terminals, face dwindling ridership, while its operators face mounting cost pressures despite a 2022 fare raise to $60 per trip. For the fundamental reason of a greatly changed Singapore urban form outlined above, even if LTA and APAD fully succeed in eradicating its unlicensed counterparts, ridership on these taxis are unlikely to ever rebound, unless steps are taken to broaden their reach into residential areas, and desired destinations on both sides of the border.

It goes without saying of course, that even in the new era, cross-border bus services introduced on the Singapore end to partially mitigate the access issues of legacy cross-border transport options face significant challenges muscling up the resources needed to meet the vast demand of non-driving cross-border demand. Every day without fail, thousands of commuters pack into buses on Service 950 (plying between Woodlands interchange and JB Sentral via the Causeway), and with the insufficient roadspace available (even after segregating buses from general traffic), it quickly gets ugly when a delay begins to pile up. A similarly painful story can be told of buses 160 and 170 that link to Kranji MRT and beyond, although having a dedicated circulator variant (170X) shuttling only the cross-border sector, on top of a hyperfrequent CW1 run by Malaysia, makes life a tad more bearable here.

Where RTS comes in

This should have been mentioned much earlier in the article, but it goes without saying that the Causeway is the busiest land crossing in the world, with anywhere between 350,000 and 500,000 people crossing between Malaysia and Singapore daily. It is no wonder that the Causeway (and sometimes even the Second Link in Tuas) is permanently jammed by day, and sometimes even by night. With insufficient cross-border public transport capacity, where else can the remaining hundreds of thousands go, except by a flood of cars that overwhelm checkpoints on both sides? The RTS Link offers a higher carrying capacity across the Causeway, surpassing that currently offered by even the braid of super-frequent bus services linking the NSL to JB Sentral (160, 170, 170X, 950, CW1). Additionally, at least on the Singapore end, the RTS Link would be linked to the MRT network (and hopefully a bus terminal, although plans for the Woodlands North ITH have been indefinitely shelved), which should enable relative ease of access for passengers originating from the various heartland towns compared to legacy options in the city.

Learning the lessons, even before it begins

Despite the first Woodlands North-Bukit Chagar RTS line being about a year away from opening, its tumultuous past enables us to begin drawing lessons from the experience of planning the world’s first high-ridership cross-border rapid transit line. In the context of Johor’s Chief Minister proposing a second RTS, these are lessons we could well draw from, from which the second RTS may even surpass expectations laid upon the first, all of which would work to the benefit of enabling a more porous border in the JS-SEZ.

Undoubtedly the RTS Link will mark a significant improvement in cross-border travel compared to today. Major areas for improvement however, remain. Coming to mind immediately was the flashpoint which almost cost us the RTS Link entirely — train capacity, which was seriously downsized during the Mahatir administration (2018-2020) over concerns of cost. What was originally intended to be TEL-sized trains with a capacity of between 1000 and 1280 passengers (depending on how one defines train capacity based on passenger comfort), was downgraded to smaller trainsets with a capacity of 607. That’s a drop of about 40% to 50%, and as I pointed out in an old post four years ago, would simply not cut it in realising the goals of better mobility between JB and Singapore. Against an expected throughput of 35,000 to 40,000 ppdph that a TEL-sized system can offer, the 10,000 ppdph offered by the downsized RTS is unlikely to make a meaningful dent in easing traffic woes across the Causeway, and whether it can effectively relieve the many overcrowded cross-border buses is similarly suspect. In the greater picture of more than 400,000 people crossing the Causeway on an average day, 10,000 ppdph is a drop in the bucket.

(Let’s just face it though: the RTS and other similar transit-related fiascos of Malaysia during that time were just petty politics to stick the finger to the then-ousted UMNO, which led the development of projects such as the RTS Link, Singapore-KL HSR, and a couple others around the Klang Valley).

I got called alarmist for suggesting that the downsized RTS would be insufficient to meet cross-border travel capacity, with commentors stating that “not all would shift to RTS”. Perhaps they had a point in the past, but with closer integration of Johor and Singapore imminent which may give rise to more frequent cross-border travel patterns by businesspeople and workers alike, the 500,000 daily throughput figure for the Causeway alone is expected to rise, and likewise solutions would need to be found to ensure the RTS is well-equipped for the increase in cross-border trips made with the JS-SEZ in effect.

The RTS is also what’s known in transit planning as a “relay service”, used to bridge gaps in the network typically across chokepoints. Rather than having multiple routes flow across, relay services act as shuttles that connect to hub stations on both ends to minimise overhead. This places serious requirements on capacity as stated above, but also offers the extra disadvantage of adding two to transfer counts — one to the relay, and one from the relay to the next service of choice. Understandably, these choices are made with current conditions in mind — with the need for full immigration procedures before granting access to the other country, it is most logistically conceivable to break the Bukit Chagar extension into a separate line, even if the choice was made to operate it as a technical extension of the TEL.

Of course, this arrangement remains inconvenient for those who value fewer transfers (and the hassle of making them, when in larger groups or when hauling larger bags), who form the basis of demand for non-sanctioned transport options today. Furthermore, Woodlands North remains far for many. Yes, special office parks are being developed around the future Woodlands North hub per URA plans, and a similar development (Woods Square) opened beside the Woodlands Civic Center one station away in recent years. It’s still a 40-minute ride from the city, and if either origin or destination aren’t located along the NSL or TEL, this can take much longer too. These are boundaries that experiments with future cross-border rail transport should aim to push, in order to fill in the gaps left in the cross-border transport diet.

Last but not least, it’s worth noting what more can be done to boost connectivity within Johor too. With most of the proposed key JS-SEZ landmarks located around the periphery of Johor Bahru, their transport options must match the investment put into their upstart to be truly plugged into the grid of regional hubs anchoring the entire SEZ. If one takes a look at the proposed JS-SEZ map again, many of the identified economic clusters are located deep within the eastern and western flanks of the larger Johor state, far from established and planned cross-border transport hubs, be they at Larkin, JB Sentral, or Bukit Chagar. For the matter, some of them are also out of range of the upcoming IMBRT system too.

Envisioning RTS 2

From the lessons learned in the first RTS Link, paints a picture of what a proposed second RTS could look like, this time spanning the Tuas and Iskandar Puteri regions.

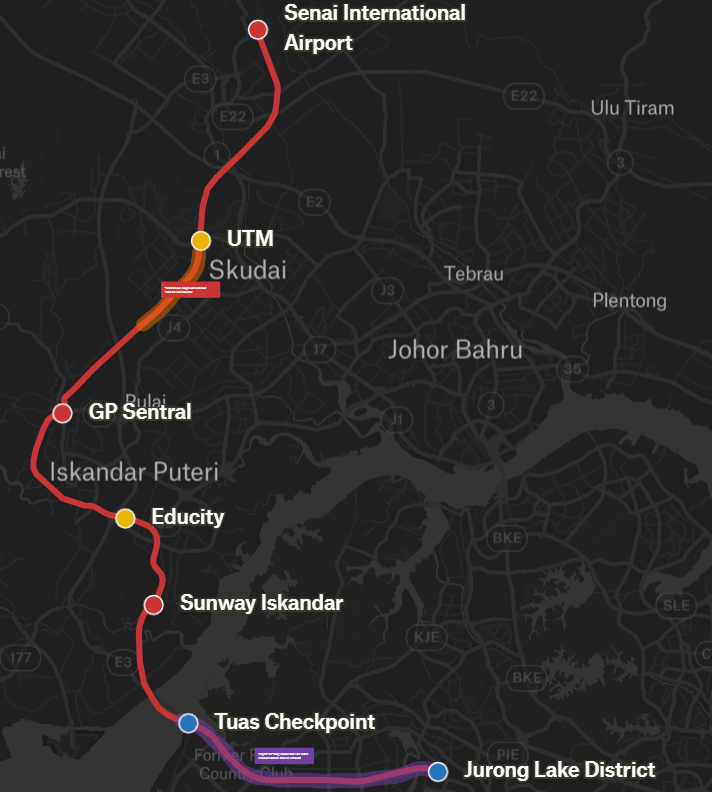

With the first RTS making the mistake of leaving itself unable to expand further to other places of key interest in Johor (the track alignment runs to a dead end to the north inside the Wadi Hana depot), the second RTS should seek to penetrate deeper into the hinterlands of both Johor and Singapore to maximise access, and catchment to otherwise totally-unserved areas in Johor by public transport. Aligning most of the SEZ’s key amenities west of JB Sentral may be more than a convenient coincidence — it is an invitation for RTS 2 to extend further to link these nodes with each other, and to vying businesses and consumers located in Singapore.

On the Singapore end, the most transformative design choice that can be made for RTS 2 would be instead to locate the co-locate the line’s terminus with the proposed upcoming HSR in Jurong East, together with the CRL’s Jurong Lake District station and a stone’s throw away from the NSEWL / JRL station of the former name. Granted, that would deflate ridership on the EWL’s Tuas West Extension (nobody says we can’t add a connecting station there, or continue to maintain a steady braid of buses operating to more local destinations in western Johor!), but a conveniently-located second RTS would completely turn the tables for cross-border travellers seeking alternative options that offer greater convenience and access.

What’s important is that unlike the first RTS, having RTS 2 terminate in the Jurong Lake District would enable near-immediate connections to four rail lines (NSL, EWL, JRL and CRL) versus the RTS’ singular TEL connection. Already, this improves access to high-capacity, high-speed cross-border public transport significantly for many more Singaporeans, and that is before we get to the many more additions to RTS 2’s catchment in the form of buses that link to the Jurong East or Jurong Town Hall bus interchanges.

On the other end, RTS 2 should not see itself merely as a “train-bridge” between the landmasses of Singapore and Malaysia. Having penetrated deep into Singapore to access a regional transit hub at Jurong East, it only makes sense for it to do the same in western Johor too, especially given the lack of viable public transit in the area — an RTS line that simultaneously doubles up as a key trunk corridor in the JS-SEZ can be the catalyst for building a network of connecting bus lines where there had been next to none previously. A basic hub-and-spoke system formed around RTS 2 today is the seed that will grow into a well-developed public transport network spanning Johor twenty years after, as comprehensive as seen in Singapore today.

For Johor residents, many of whom live in areas generally west of JB Sentral, their Singapore-bound commutes are low-hanging fruit to attain immediate ridership success for RTS 2, and it’s definitely with this consideration in mind that Malaysian leaders are bullish on the idea. But they must take utmost caution to avoid the mistakes of the first RTS, particularly when the bulk of this population lives at least 10km away from the Second Link checkpoint — a distance clearly unwalkable, and even more so in the auto-dominated landscape characterising suburban Johor. This is not a request to expect RTS 2 to serve every residential estate in western Johor — but minimally, it should penetrate sufficiently deep into the state’s hinterlands to serve the areas that matter as part of the JS-SEZ, as well as connecting to the IMBRT’s Iskandar Puteri line at one point at least. Ideally, additional connections to major bus hubs, where commuters already transit through to cross the border, would further enhance the ability of RTS 2 to secure its position as a leading driver for growth in the western Johor area.

A gift, from the past

The fallout from last decade’s stalled cross-border transit initiatives has left a significant mark on land use plans in western Singapore. Whilst cancelled, the HSR project blazed a trail that paves the way for its eventual return along the same route crossing the Johor Strait at its far-western end into Singapore and linking to its reserved Jurong East terminus. In the meantime however, with political realities up north disfavouring active development of HSR along the single most busy air corridor in the world, other uses may be sought for the land that has already been acquired, and now sitting idle.

That’s where RTS 2’s extension into the future JLD hub comes in. Running on the rights-of-way once planned for the HSR, it will fulfil a more immediate need for a more thorough cross-border rail link with relatively less effort needed. RTS 2 is the key missing ingredient in igniting the potential of the JS-SEZ. In turn, the impact of the JS-SEZ in reshaping the Malaysian and Singapore economies will bring back a similarly strong case in favour of the HSR to be built. I envision RTS 2 as less of a standalone shuttle train across the Second Link, and more of an expansion of the HSR’s Shuttle service (Iskandar Puteri – Jurong East) to go beyond the limited scope allowable in the initial HSR plans.

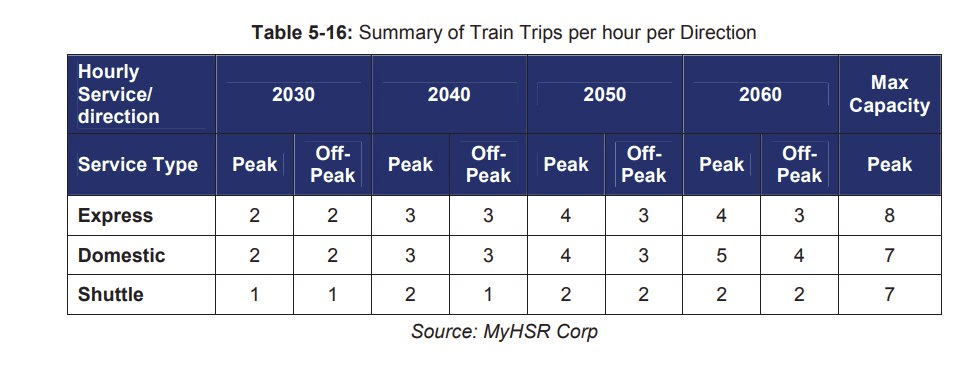

Few would need to worry about RTS 2 obstructing valuable track space on the HSR — for one, according to plans made prior to its demise in 2021, the HSR would not be operating frequently for a very long time.

With plans to run trains only as frequently as every 20-30 minutes even as far beyond as 2050, ample space is left for RTS 2 to thrive within the wide spaces of the planner HSR timetable. For reference, Hong Kong’s East Rail Line used to share track with a non-stopping Kowloon Through Train and direct trains operated from the mainland, which passed through about once an hour. Yet the EAL continued to maintain a steady 3-4 minute frequency throughout the day despite their presence still. On a line-sharing arrangement with less significant differences in stopping patterns, and potentially operating speed, much more room exists for RTS 2 and HSR to coexist on the same pair of tracks, potentially for as much as 30 years, assuming an operational date in the early 2030s.

Despite talk of the HSR line being built underground within Singapore, there’s still likely to be some form of speed limitation imposed on our side of the Second Link, presumably to around 160km/h. These are speeds that are well manageable by even RTS 2 trains sharing the tracks. A good gauge of what would fit well on RTS 2 would be trains similar to those on S-bahns in Europe, or the regional commuter rail lines operated by China Railway in various cities.

Hopefully, in conjunction with the ongoing IMBRT project, and plans to establish Komuter service in Johor, RTS 2 can seed the future for rail rapid transit to take off in Johor, forming a larger network spanning the entirety of the JS-SEZ. With key amenities spread out over a large area and projected demand for more travel in the years to come, the conventional logic of prescribing against rail for the lower-density urban form around JB holds less water. The best time to build rail in Johor was yesterday. The next best time is now.

The wall

Of course, this talk about building abundant cross-border public transport connectivity (as well as across the border) is fine and dandy, but one major practical consideration continues to stand in the way of making seamless cross-border travel a step closer to reality. Ultimately, Singapore and Malaysia remain two sovereign entities on either side of the Johor Strait, and little plans have been discussed in the JS-SEZ in relaxing or lifting border control procedures. Both nations also maintain conservative attitudes towards liberalising cross-border movements too, so it is too early to expect immigration rules to bend in favour of more open cross-border transit options.

Still, this should be of little deterrence towards realising RTS 2’s vision of jointly strengthening cross-border public transport, and building towards Johor’s own rail network. For the purpose of enabling free travel between Malaysian stations on RTS 2, it would be an acceptable compromise to situate immigration checkpoints (jointly managed by the Singaporean and Malaysian authorities) at both the Jurong East and Tuas Link RTS 2 stations, leaving stations within Malaysia entirely immigration-free. This would encourage local ridership within Johor to augment cross-border demand, creating a viable and self-sustainable rail link driving growth in the region in the shortest time possible. As for our side, the EWL (and in future, the CRL too) already exist to connect passengers between Jurong East and Tuas. We can afford to be “locked out” from local connections on RTS 2.

Here’s a concept of how RTS 2 could potentially work, utilising existing safeguarded land for the future HSR, and connecting to multiple key nodes and planned public transport corridors in western Johor. With minimal modifications made to longstanding public transit plans on the Malaysian side, RTS 2 can achieve a much greater effective penetration rate into local communities and businesses than the current RTS is capable of, while simultaneously forming its own major corridor too. With trains capable of operating up to 140km/h (similar to Shanghai’s Airport Link Line, or Guangzhou’s Lines 18 and 22), the RTS 2 will shorten a full trip from Jurong East to Senai Airport from more than 3 hours today to a mere 45 minutes, immigration permitting.

A trip from downtown Singapore to Legoland, once a 4-hour journey, would take only 90 minutes. (And if we extended an express rail link from JLD to the city, this would go down to 70!) For a Gelang Patah resident who commutes to work in Tuas, what was once a journey taking 2.5 hours will be slashed to just an hour, with the waiting frequency of the connecting bus to their Tuas factory now being the main source of uncertainty in the trip!

Continuing on the legacy of RTS 1 in Woodlands, RTS 2 will become a key gateway to western Johor for travellers arriving from Singapore’s Changi or Johor’s Senai airports alike, and promote high-quality development in the Iskandar Puteri region, which the Johor state government has been eyeing as the next big thing in the area for a very long while, with mixed results (see: Forest City).

Of course, the eventual long-term goal is to hope that the increased economic activity and people-to-people exchanges fostered through the JS-SEZ will nudge us towards greater integration, where immigration barriers are partially, or maybe even fully removed, in a sort of Schengen-like arrangement. That would be the ultimate aim, although it’s anyone’s guess when that would happen, if ever.

Anyway, let’s not be swayed too much by the special “RTS” branding that these cross-border rail proposals carry. At the end of the day, if we want to truly realise the vision of a more integrated Johor-Singapore SEZ, it means working together to enhance transport links, such that these barriers to cooperation get progressively torn down. What label they carry, and any special characteristics they may possess, are secondary to the vibrant and dynamic futures of both Johor and Singapore.

Interested in building a better future for Singapore’s transport? Join the STC community on Discord today!

Leave a comment