For once, this isn’t about a strategic policy mistake on LTA or MOT’s part. Yet, this general industry trend in autonomous vehicle development demonstrates, to put it diplomatically, a collective historical amnesia on why public buses, and public transport by extension, were evolved in the first place.

Earlier last year, I had the opportunity to attend the World Cities Summit 2024 and SITCE 2024, where urban designers and mobility providers from all over the world attempted to impress with their most advanced technologies. Besides the diverse smattering of offerings from three-door bus designs (ew), intelligent control systems to sustainable solutions, another common theme presented was also that of automation, principally of providing autonomous bus solutions. After a while, I’ve come to realise how predictable such products are, which wouldn’t be an issue until they’re actually realised on a large scale.

What comes to mind when “autonomous buses” are mentioned? If one has closely followed developments in this field over the past decade or so, the common impression is likely to deviate significantly from the average person’s understanding of a conventional bus — small, driverless pods which can carry about two dozen passengers at most, or usually even lower. There may also be a tendency for these to ply on-demand service patterns, rather than following fixed routes compared to traditional buses, which is a feedback effect arising from their lower vehicle capacity.

Of course, this doesn’t mean full-sized driverless buses haven’t been trialled before — Singapore has tried those out within the NTU campus (alongside the pods above), as well as attempted to produce our own 12m autonomous bus in partnership with Linkker, though both of them bit the dust last decade, with the NTU bus rotting away in a corner, and the Linkker partnership getting shuttered due to insufficient funding. Overwhelmingly however, the prevailing trend in the AV industry is still to “shrink” the size of buses upon automating them, regardless of the intended use case.

Here’s a bold proposition: This very “shrinking” of autonomous buses plays an equally large, if not larger role in slowing down the automation of buses than the technical complexities of attaining Level 4 automation in complex urban environments.

Simply a matter of scale

Here’s the kicker: attaining Level 4 automation is actually very easy provided a few conditions are met, all of which can be easily provided for without too much rocket science:

- A protected operating environment, which basic bus priority can effectively offer.

- Sufficient computational power to store and process individual use cases for each given route. A non-issue either, provided the former condition is met. Heck, higher-end personal computers are probably powerful enough to run one of these autonomous buses even!

- Sufficient sensory input, from a mix of video technology, LiDAR and GPS to enable the vehicle to make sense of its surrounding environment. As every AV trial has demonstrated, this has long been surpassed too.

Why then, hasn’t Level 4 (or even Level 3!) automation arrived en masse for public bus services then? The answer is simple: because the current conception of autonomous buses as autonomous pod shuttles is unscalable to the size and scale at which public bus services operate at today! Notice a common characteristic present in every autonomous bus “trial” involving these shuttles — all operate in relatively isolated environments, on simple routes, with low expected demand involved. Such an operating profile could perhaps augment, but not replace standard bus service in the transportation mix! At the small scale which these trials occur, the pod-based model of designing autonomous buses appears a promising way to offer more personalised service. Yet, this would fall apart completely if placed in an environment demanding more capacity. As Jarrett Walker would have said of microtransit, which these pods more closely resemble, if it doesn’t scale, it doesn’t matter.

The glass ceiling, or why transit was invented

As everyone familiar with the design and planning of public transport systems would be acutely aware of, given sufficiently high demand for a bus or train service, there will come a point where simply adding more buses or trains to the system will just cause gridlock, resulting in decreased performance. (Or, in the case of trains usually, the infrastructure simply limits you from adding more trains, which was why resignalling was a big deal for us in the early 2010s)

This limit thus forms the glass ceiling of transit, at which carrying capacity cannot be further increased through adding more vehicles. By the way, it applies to other modes of transport too, and a similar glass ceiling for cars for instance would be defined by the point at which total gridlock has limited the throughput of an expressway, for example. It is important to note that despite its metaphorical origins, the glass ceiling of transportation is very much a physical constraint dictated by spatial geometry, and some math.

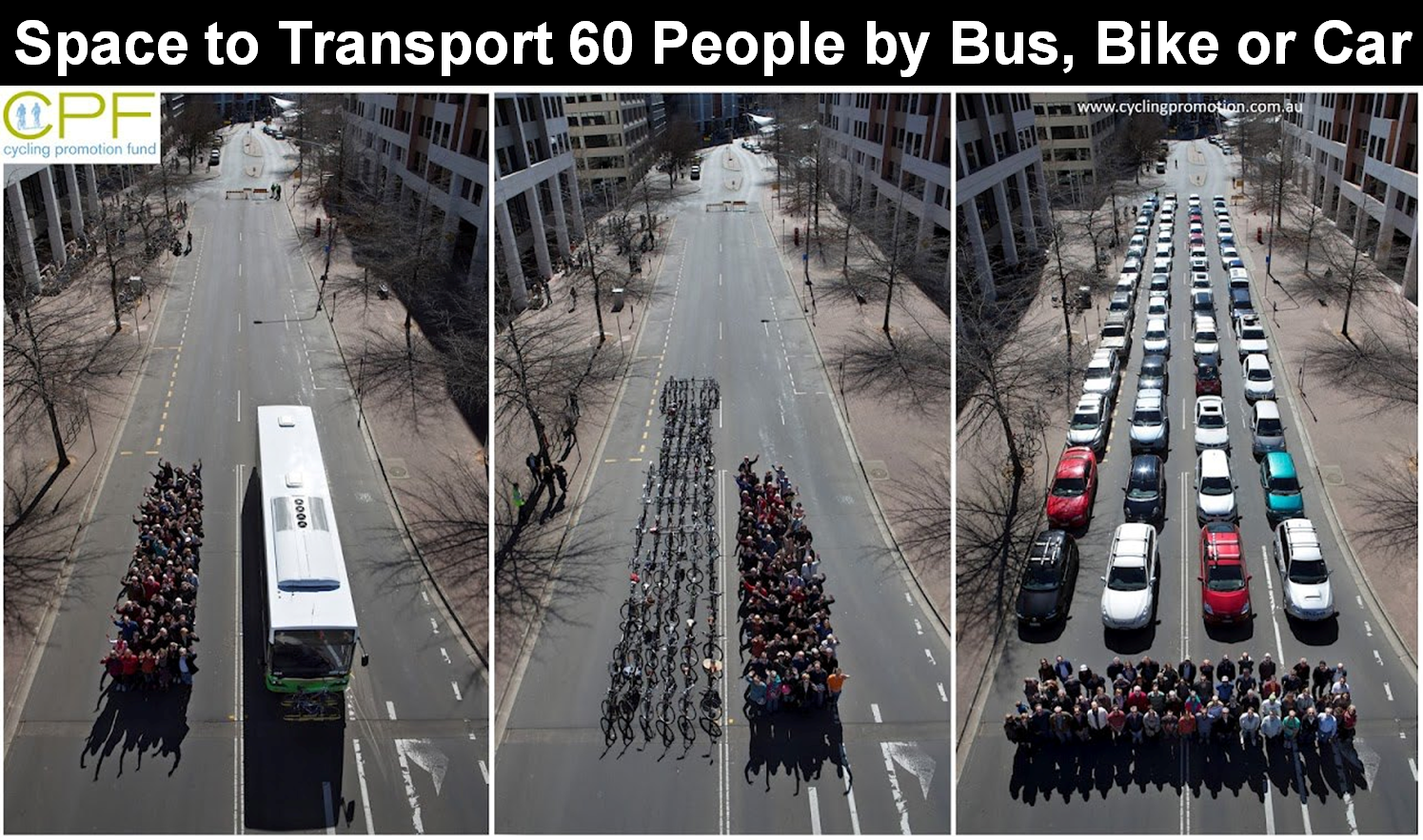

When the glass ceiling has been reached, the only way out to further increase throughput is to increase the capacity of each individual vehicle, such that the total number of vehicles required to meet throughput decreases, re-opening space to further increase capacity. That’s the basic logic behind any public transport mode vis-a-vis mass driving — cars take up a lot of space on the road with very low capacity, whereas a public transport vehicle could carry up to a hundred times more people while taking up just a few times more space. You might have seen this infographic circulated around before, which perfectly illustrates the capacity glass ceiling phenomenon of different modes of transport. At just 60 people, the car-based option has hit its limit by filling up the entire road, while there’s still ample room to further increase throughput on bus-based or bike-based options.

Having a higher glass ceiling than a fully car-based approach is what makes public transport so essential in any urban strategy to reduce congestion and create more livable spaces in highly populated urban environments. Much in the development of public transport vehicles over the past century has in fact been the study of how to fit more people into the same vehicle, and how to fit more of such vehicles into the same systems without compromising performance and efficiency. (The Japanese took the former a bit too far, to compensate for their lack of progress in the latter, for instance) Both of which are just fancy ways to say, how can we push this glass ceiling further up to not get crushed by our cities’ burgeoning populations.

Fake trains, and desiring APM lite

Especially regarding self-driving vehicles, which many seem to have unrealistic fantasies about. Around some corners of transit discourse, there seems to be an odd fixation upon the ability for computerisation to resolve the glass ceiling without a meaningful increase to capacity, or a similarly quaint belief that it’s an either-or choice between frequency and individual capacity. In the latter case, the belief is that transit vehicles can be “blown apart” when the driver is removed, providing higher frequency at lower capacity, as if the driver is the sole impediment of providing more frequent service.

Regarding the former, promised technologies such as virtual chaining of driverless cars together to form convoys have created the false belief that the glass ceiling’s physical limits no longer apply to the world of urban transportation. It’s also the errorneous logic that leads one to conclusions such as those claiming self-driving cars would make public transport obsolete, the same absurd conclusions that swept the United States last decade when ride-hailing and car-sharing first took off.

While it’s best not to give such fallacious propositions further airtime (especially not on this site), there’s still a need to dispel the false notions behind these ideas, and some simple calculation of throughput easily demonstrates the continued relevance of keeping in mind the geometric limitations dictating how urban transport operates. Having learned and written much about public transport for the past five years, I’ve once been told to give up on the field due to the impending takeover of urban mobility by the swarm of driverless pods (sounds very techbro?), which would supposedly move more people than traditional public transport because of their ability to stick closer together (as a result of computerised control). Of course the incorrectness of its logic doesn’t require further elaboration, but for the skeptics, here comes the numbers.

Take a pod with a capacity of eight, which is standard fare for most “pod-based” systems being marketed as replacements for standard public transportation. Assuming the technology is perfected to enable these pods to operate in a linked fashion, and assuming we manage to create an insulated environment for these to operate in, the need for these vehicles to stop and dwell for passengers to board and alight will still inevitably require some sort of spacing to avoid fully gridlocking the system. Let’s say we give about 20 seconds, which is tight, but manageable in a world filled with homo economicus and 8-seater pods. (I’m already being more generous than its proponents do — their suggestions indicate a proposed frequency of 3 minutes per pod to replace existing bus services operating every 8)

This works out to be 180 vehicles per hour, or just barely 1440 passengers per hour per direction, for best performance. To hit this throughput, only 12 double-decker buses are needed (average headway 5 minutes), or one single six-car MRT train (capacity 1500, arriving once every hour), which leaves lots of room for further increases in service to meet increasing demand. Remember that these numbers apply on a corridor level, which is the sum total of all services on different routes operating together on a given piece of infrastructure of that particular mode. To give you an idea of how sparsely-served a corridor with only 12 buses per hour is, bus service 190 alone (once famous for being the poster boy of overcrowded public transport in Singapore) operates at this frequency during peak hours, alongside numerous other routes along the various roads it plies. All without clogging up the road significantly, despite a seemingly high bus throughput. Any six-lane road in a decently-populated part of Singapore gets better service than 12 buses per hour too, for what it’s worth.

But at this throughput, a system entirely dominated by self-driving mini pods begins to fall apart. Only somewhat better than an entirely car-based system, but far short of existing public transport modes. Yet such a system is envisioned to be the future of public transport by the automotive industry producing its fleets, to replace the big buses that provide adequate capacity to meet large urban demand today?

Or why animals didn’t evolve wheels

This ties in somewhat to the previous post on automation — an imagined future that can be realised is one that can be evolved from the status quo. Spherical cows sound great, until one realises there’s no intermediate stage of realisation for such a system. In the case of these envisioned “endless AV convoys”, having to share the road with manned vehicles that are unpredictable in the eyes of the computers means many of the touted benefits will simply not materialise, because their perfect formations will inevitably be disrupted by non-driverless vehicles. And if a dedicated lane were to be set aside for them to create such an environment, it would only make more sense to further maximise the capacity of the services on them to maximise returns off capital-intensive infrastructure. That would push the evolution of autonomous vehicles in a radically different direction, one that aims to replicate the successes of driverless rapid transit, except on the road in more protected conditions, less the additional capital costs in constructing grade-separated rapid transit. So instead of getting driverless pods every 20 seconds, that vision might evolve to resemble something more like full-sized driverless buses every 60 seconds, operating in a fashion more similar to automated people mover systems seen today.

To build tiny pods with highly limited capacity would perhaps make sense in sparsely-populated environments with highly unpredictable demand, but is squarely incongruent with the realities of evolving a driverless transport system in big, dense cities. For high-density suburban areas that have evolved their own urban character like our HDB satelite towns, it might find itself in stark rejection of products that won’t fit down limited road space within them too.

The North American mind virus

These conversations around a “shrunken” future for public transport are an extension of a mentality, most prevalent in North America, where frequency becomes the be-all and end-all goal at the expense of disregarding a given mode’s maximum capacity limitations. For some strange reason, frequency (a benefit unlocked by automation) is deemed mutually exclusive to individual vehicle capacity. Heavy rail commuter services are compared against Vancouver’s driverless Skytrain system. Conversations about urban rail transit devolve into false dichotomies between manned heavy rail subways against driverless APM technology (as if that can even be considered rail). And in the discourse surrounding automated road vehicles, it’s between driverless pods and big traditional city buses. The biggest driverless “bus” produced so far in North America, for what it’s worth, is Elon Musk’s 16-seater robotaxi, still a far cry from the 80-strong capacity easily handled by a typical 12m bus today.

Many factors go into shaping such mindsets, such as the general lower density of North American urban areas (the “empty buses” fallacy, which automation does nullify), reduced capital investment required, and maybe the lack of education on how multiple unit traction, not train size, is the real determining factor of how quickly trains can start and stop.

But that’s beside the point here. At its core, such a view of transit ignores the different extent of policy space each design choice offers. An APM every 90 seconds with a capacity of 250 each might carry the same number of people as a light metro with a capacity of 900 every 6 minutes, and might even cost less than the latter, but when demand for more capacity arrives from induced demand, one will have far more room for potential expansion than the other. Those who built the APM will be left wishing they had picked something with greater capacity, while those with a relatively infrequent light metro will do the more inexpensive thing of simply buying more trains to run more frequently.

Likewise, “right-sizing” transit vehicles to snugly fit current demand patterns (whatever the heck that means, including shrinking buses when they get equipped with Level 4 and above) looks like a financially prudent move, but the cost of having to re-expand everything, or living with a gridlock of tiny driverless pods on the road, will far exceed the perceived wastage of big driverless buses running half full. Because a slightly less frequent service with bigger vehicles can afford a latency that the ultra-optimised vision pushed by the busmaking industry cannot.

It’s sad that even in Singapore, as far away from North America as one can get, this mind virus has still caught on in our own automation efforts. LTA’s recently-launched autonomous bus trial (to begin in 2026), against expectations from previous projects, feature smaller 16-seater minibuses. While arguably a design choice based on the low ridership of the two selected trial routes (191, 400), its worrying that there’s neither the intent nor interest to pursue full-sized autonomous buses, when the technology presents itself ready to hit the road. A lack of interest that is unfortunately also shared by those thinking about urban transportation here. In old concept renders of Tengah (and now the JLD too), driverless pods not much different from PRT were advertised as “smart” transport solutions for these emerging areas. How “smart” is it then, to get caught in a gridlock of pods when they find themselves lacking in handling high expected passenger demand, not least in the next urban core up west? Definitely not something to be gloating about in URA’s galleries as examples of shining urban innovation.

Breaking through, and good news

When will automation in buses truly take off then? With nearly a decade having elapsed since the earliest driverless bus prototypes emerging, the slow adoption of self-driving technology in the bus transit industry points squarely at a picture of a wrongly-evolved autonomous bus product generally available on the market, remaining largely irrelevant to the demands of their target customers, not because of technological constraints, but rather its spatial limitations that limit their usefulness in our cities.

To be fair to these driverless pods: They may find themselves a use, just as Personal Rapid Transit managed to weasel its way into the transit mix in limited applications such as universities and airports. In Singapore, they could potentially find themselves useful in low-density landed estates or Lim Chu Kang, where they serve as more cost-effective means at expanding coverage into these ulu areas than traditional feeder services can. But wherever they may find themselves genuinely needed, their utility will continue to remain governed by the same framework that governs mode choices in planning transportation networks elsewhere — the capacity glass ceiling. Where demand lies above the ceiling for such little pods, it’s clear it’s time to upgrade to something bigger.

The good news is, while many bus makers still preoccupy themselves with fancy toys of little practical value to urban transport, some are beginning to explore bringing the driverless technology to where it matters. In the previous post I’ve shared the examples of Yutong’s situational automation applied in Zhengzhou, and a trialled driverless BYD K9 in Narita Airport. Of course, there’s one more trial halfway across the world that I would be doing a disservice to not mention here too.

In what’s probably the closest replication of full-sized fixed route driverless bus service, route AB1 between Edinburgh and Fife in Scotland, UK was launched with autonomous Alexander Dennis Enviro200 buses in 2022. While it’s applied to a more suburban route profile with lower traffic (and lower ridership, which ended the project earlier this year), it gives a good look of what autonomous buses should strive to resemble in order to take off. With a similar capacity to an equivalent full-sized bus today, operating a larger fleet of these in an urban environment would offer meaningful cost reductions whilst providing greater service where needed.

More importantly, lasting nearly three years (in the uncertain post-pandemic period no less) despite low ridership is a significant feat, considering how similar trials involving autonomous pod shuttles count their longevity in mere months. A simple fact that by continuing the maintain the high glass ceiling that traditional buses have had for decades, full-sized driverless buses find themselves relevant in a larger range of situations (which unfortunately did not include the Scotland trial).

With Level 4 automation on buses increasingly reaching maturation, what’s critical to ensuring their rollout to wider urban transit applications is the nature of autonomous bus products, which consequently decides its resulting target audience. Removing the driver shouldn’t mean blowing apart an infrequent bus today into many little pods — it should mean the ability to operate more big buses more frequently at equal or less operating cost than seen today. This would be the real game changer in the public bus industry, offering highly needed relief to operators and agencies who walk an increasingly thin tightrope between demand for increased service and an ever-shrinking manpower pool.

As boring as it seems, perhaps the future of buses, Singapore included, might well be the bus you see today, sans the driver.

Important TM50 update!

If you aren’t already aware, STC has recently launched the website for our Transport Manifesto 2050, our alternative blueprint to LTA’s upcoming Land Transport Master Plan!

Every TM50 initiative and proposal will be featured here (under the respective pages, which can be found by navigating through the “Key Initiatives” page) as they’re progressively released pending completion, and also serves as our platform for reaching out to you, the average Singaporean commuter on our public transport system! Additionally, we’ll be releasing helpful explainer posts behind proposals put forth in various aspects of the Manifesto which may require further clarification. As a ground-up project, we believe in having you on board, and that includes keeping you in the loop with our decision-making processes. To make the most out of this journey, I’d highly suggest subscribing to the TM50 website to ensure you don’t miss anything from us in the next few weeks!

When fully released later this year, the final TM50 reports will also be published on this website too. Stay tuned as we continue releasing more proposals, initiatives and early teasers leading up to the final publication of the Manifesto! Thank you for your support to the STC Team and TM50!

Interested in building a better future for Singapore’s transport? Join the STC community on Discord today!

Leave a comment