Looking beyond the headlines, and reviewing the annals of transport history on our little red dot, one would surprisingly find that trunk services are not the biggest victims of bus rationalisation exercises, at least not since the 2003 NEL rationalisation. Contrary to what I’ve constantly been writing about here, the group bearing the greatest brunt of bus cuts is actually express bus services, which are overwhelmingly the first to receive the axe when such exercises occur. A second worrying trend also exists — express services, at least in Singapore, are short-lived, by perhaps unintended design.

Of the more than 50 routes incorporating express sectors formally branded as Express (or some derivative) and Fast Forward that existed at various points in our bus history, only 18 remain in active service today, and among those only two operate more frequently than 15 minutes on a consistent basis, with the rest either operating at (half-) hourly intervals or only during the peak. These exclude the City Direct services, which are designed to funnel people into the CBD directly from heartland areas, which often result in deliberate missed connections to avoid market leakage. For instance, 663 and 670 skip the pair of bus stops serving Khatib MRT, and 652 skips two pairs of bus stops serving Ang Mo Kio MRT and bus interchange.

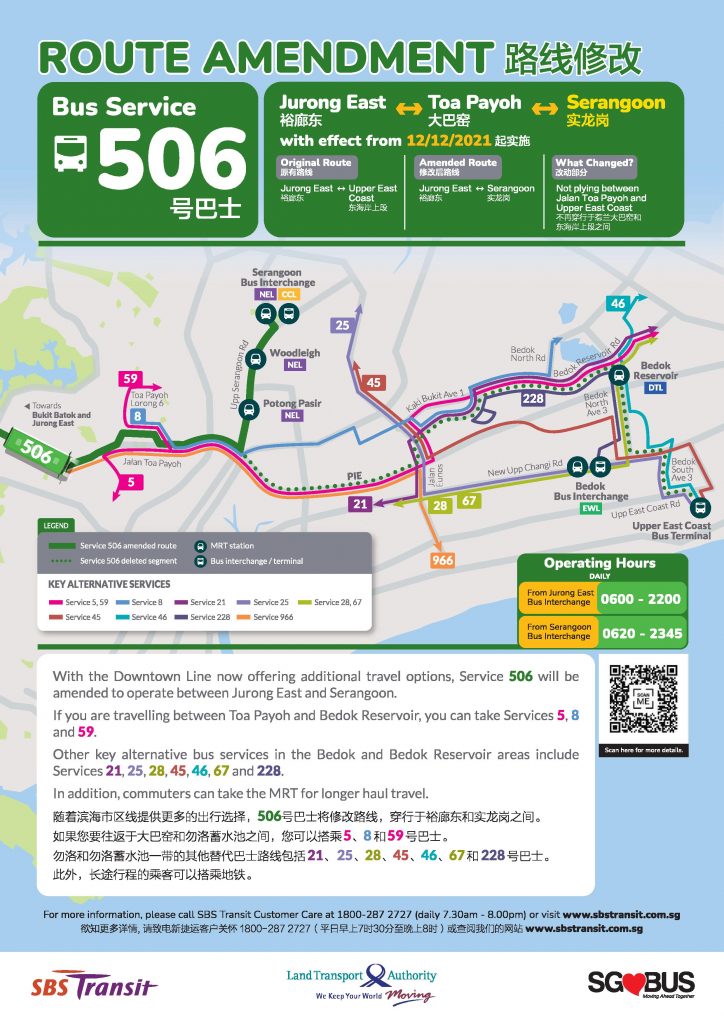

Having 18 express services still in existence might not sound too bad, but for the vast majority of people who may potentially benefit from the presence of these expresses, they are as good as useless. Most of these, especially those formerly branded Fast Forward (using the “e” suffix, rather than the 5xx series service numbers) operate limited unidirectional trips during the peak period. As mentioned above, only two express routes (502 and 518) operate with all-day service frequencies matching similar trunk and long feeder services. Only one more (506, recently shortened) offers consistent bidirectional service throughout the day. Three more (12e, 851e and 960e) have a service span longer than just merely the peak period, but still greatly limited in operation hours in each direction, running once or twice an hour. In total, that’s just six (or seven, if you include 89e for running a dozen trips each way or more) surviving express bus services across all of Singapore that aren’t just City Direct wannabes, attempting to offer some form of all-day fast service that offers sufficiently significant benefits for residents in catchment areas to remotely consider taking them.

And few of these express services can be considered to be surviving well — many hang upon a thread, with the grave risk of being removed anytime soon. In fact, many express services like the ones still standing today have historically been removed en masse, either as part of MRT rationalisations or simply because LTA could not justify their operating cost. When the North-East Line opened in 2003, many trunk routes were simply cut short to remove duplication, or amended away to form the crosstown routes so valued today. Express services (numbered 5xx, introduced as distinct routes by SBS in the 1990s) were simply withdrawn.

In more recent examples, 74e and 151e were removed in January 2022 after 15 years of service. 147e and 167e, both introduced in 2018 to alleviate crush loading on the NSEWL during re-signalling works, were withdrawn successively in 2020. Hell, similar stories could also be told of the Chinatown Directs and the recreational expresses to Sentosa! It’s not as if other expresses escaped unscathed — 12e, 851e and 960e, introduced together with 147e and 167e, had their operating frequency and span continually reduced starting 2020, to the point that 851e was no better than the CT8 it was supposed to supplant! Looking forward into the future, sayings exist that three more expresses — 10e, 14e and 196e are slated for withdrawal as part of TEL4 service cuts, while it’s still uncertain whether they will attempt full route cuts to trunk services.

The historical trend of express services being disproportionately vulnerable to service cuts reflects a failure across the board for expresses as a service type to attract (but more importantly, retain) riders, which lend it slim chances of survival at financial audits, be they conducted by SBST of 2003 or LTA of 2023. To be clear — expressway buses (such as 168, 190 and 969) are a separate matter altogether, and these perform superbly well in ridership terms as they enable affordable and quick rides to cover large distances, for the intercity profile of many commutes in Singapore. Why then, do express-branded services struggle to balance the books, despite charging higher fares? As it seems, the question answers itself — the fare structure of express services in Singapore set them up to fail from day 1.

This is not a dissertation on the impact of scheduling frameworks such as OTA which do play a part in making express routes less worthy due to slower rides, driving away some ridership; that matters, but it’s something meant for another post, another day. OTA itself is also a neutral tool, and how it is used to influence bus speeds is really entirely up to the way LTA regulates service quality based on it, and how operators react accordingly. Arguably, faster rides alone do not noticeably shift the balance significantly in the decision-making matrix of public transport riders either — a seemingly slower option is often more popular when moderated by factors such as access penalty, service frequency and comfort. As a side note, that’s why every attempt to cut back bus services in the name of pushing riders to MRT lines has been met with such fiery resistance from the public and bus enthusiasts alike, besides the obvious fact that it’s just a thinly-disguised net reduction of service.

I found the answer to the decline of express buses, from a couple of anecdotal encounters I had around these express buses.

For the first one, let’s go back to a time when I had just entered secondary school, some time before STC even began to exist. Back then, 74e was still running, serving as an important link between the northeast and southwest, as a useful alternative to the overcongested Circle Line. One of those days before the route was deemed unprofitable by LTA, I was waiting at Ang Mo Kio MRT in the evening to take an eastbound bus, and one of those 74e buses stopped by to drop passengers off. While the bus stop remained largely packed (tons of people transfer from the NSL to the medium-capacity corridor stretching all the way to Serangoon North and beyond), a few lone souls boarding the bus here, well after the end of the express sector from Maju to Marymount, caught my attention. What were they doing, paying the extra 60 cents for a ride that is no slower than any of the other basic bus routes? Of course, few others joined them, and chose to cram on the other trunk buses arriving in quick succession instead.

The next one is centered around the city area, specifically the Chinatown-Bugis corridor which I frequented for a period of time. One of those days, I decided to ride 851e up north from Chinatown, and enjoy the new fleets assigned to it. The double-decker bus arrived Chinatown pretty much completely empty, and boarding the bus with me was a clueless old lady who asked the bus captain if the bus went to Bugis (it did, but that was before the express sector). Before I could warn her that boarding this particular bus would cost her an extra 60 cents, beep went her card on the reader. Why was she paying the extra 60 cents for a ride that didn’t justify it? I hope she realised her mistake afterwards, for it’d be quite costly to repeatedly tap on express-branded buses by mistake over time!

It was then the realisation hit — these fringe cases observed are the inverse of typical commuter behaviour that leads to the underutilisation, and consequently the demise of express bus services in Singapore! To be more specific, the deterrent to ridership on all express-branded routes here lies in the fare structure surrounding them. In particular, it’s about the surcharge that’s levied on riding express-branded services, which is fixed at 60 cents for adults, regardless of where or how far one rides the express service. This surcharge may be less for discount pass riders (30 cents for students, for example), but the point on it being a fixed surcharge remains.

The logic of overcharging

By no means is this a defense of the 60-cent express surcharge in our fare structure, but there’s a kernel of truth in making riders pay more for express bus services. This matters, particularly when we get to the next bit on engineering a fairer fare structure for express services.

Recall the concepts of cumulative and cyclical demand from the previous Basics post explaining demand cycles. Tl;dr, routes with cumulative demand, where most passengers ride end-to-end, tend to fare much worse in absolute ridership numbers compared to routes with cyclical demand, where there’s constantly passengers getting on and off at various points along the route. Express services by their very definition of getting people across from point A to B quickly by skipping catchment in between, tend towards cumulative demand profiles, as almost everyone riding them uses it explicitly to cross the long non-stop segment quickly. That’s how express routes are designed to work, after all. Of course, lower ridership caused by demand profile (emphasis from the previous post: this is not a fault of express bus services) means either of two things: more resources must be expended on moving the same number of passengers, or the same amount of resources go towards transporting fewer people, because each ride occupies a spot in the bus for longer. (For Singapore, it’s almost always the latter in the context of express-branded routes). From an economical perspective, it makes sense to charge more for riding express services, be it to account for the higher opportunity cost of operating them, or to use the price mechanism to bar some from riding them. Hence, each time one taps on an express bus service, they are slapped with additional surcharge to reflect the much longer demand cycles seen on express services.

Dying, from day one

Unfortunately, levying a fixed surcharge (of significant size) on express service riders limits their desirability to many, making them very niche offerings that attract a narrow slice of the demand pie, despite the potential of the catchment they serve. This manifests in three ways. For one, capacity utilisation of express buses is absolute dogwater outside the express sector, and this assumes the buses are even filled up to capacity there. Because a fixed surcharge is levied regardless of distance travelled, passengers are strongly discouraged from using express services within the local-stop segments on both ends of the express sector, even if they may provide a valuable additional service on top of existing trunk and long feeder connections. (One exception exists, and I’ll get to that soon)

This prevents the formation of cyclical countercurrents under the predominant cumulative demand profile that express routes are characterised by, which effectively forms a glass ceiling to an express route’s ridership. In Singapore’s context, the fixed express surcharge limits their usefulness beyond the immediate express functionality they offer, and this becomes a huge problem once competition from rail lines and non-express bus services emerges.

One exception exists to the above axiom regarding express routes: if the local sector of the express route provides a highly valuable connection not offered by any other route, the fixed express surcharge will not be a deterrent to passengers even if they make the trip on the local sector only! Take the case of 506, whose shortening in 2022 was not entirely the result of its own failing:

Despite being officially cited as “reducing duplication with DTL stage 3”, the real motive for Service 506’s rationalisation was to reduce bus-bus duplication with other local bus services plying Bedok Reservoir, such as 8 and 65. You may also realise that 506 used to incorporate a north-south segment linking Bedok Reservoir MRT to Upper East Coast, and if you didn’t grow up in this area, it may surprise you to know that 506 historically enjoyed very strong demand here, as it also played a unique long feeder role linking Bedok Reservoir, Bedok North and Bedok South, resulting in many willingly paying the additional 60 cents to cross between north and south in Bedok without having to detour through the town center. Long feeders like 46 (featured in the irrationalisation poster) and 137 that also do this job today were a relatively new introduction, both of which were only launched under BSEP from 2016 onwards. Of course, the introduction of these long feeders (which charged regular fares) began the long downward spiral for 506, as everyone who previously paid the extra surcharge for 506 without much choice switched to using 46, killing off the previously strong cyclical countercurrent in Bedok that 506 used to enjoy, which eventually led some higher powers to demand its useful eastern sector removed.

The other problem with a fixed express surcharge became apparent when TIBS pursued a different service strategy from SBS in the 1990s. Unlike SBS, which charged additional fares for faster bus services plying expressways, TIBS introduced many expressway routes that charged standard fares, a practice to continues to this day with the numerous expressway buses that commuters enjoy at standard fares with all the benefits of faster rides, most of which were operated by SMRT/TIBS at some point in the past. When the legacy express routes overlap with similar expressway routes introduced by TIBS, the express route suffers an immense disadvantage, with passengers overwhelmingly choosing the non-branded service for cheaper rides, and in the post-BSEP era, unironically faster rides too. (Thanks, OTA!) As a CotD on this blog from a while back goes, the value of many of these “faux expresses” lies in us realising the 60 cent surcharge on express-branded routes to be a scam.

The same 506 mentioned above unfortunately has an expressway trunk competitor — SMRT’s 985, sharing the same expressway sector between Bukit Batok and St. Andrew’s Village, after which both routes branch out in different directions. It manifests in a glaringly obvious manner to anyone who’s taken both routes before — whilst the expectation for riding 985 through the expressway sector is to not find a seat at any time of the day, buses on 506 are at best fully seated (single-deck) and at worst, completely empty even on the expressway. This competition between the two routes goes back decades — the introduction of 985’s predecessor (the short-lived legendary 989 from Choa Chu Kang to Changi Airport) in 2001 forced SBS to shorten 506 from its original Changi Airport terminus to Bedok because its express surcharge simply made 506 uncompetitive against 989’s standard fare scheme! (For what it’s worth, 989 also took the faster route to Changi Airport, skipping Toa Payoh and the entirety of 506’s Bedok Reservoir sector. A deal too good to be true indeed.)

Having to pay a fixed surcharge regardless of trip distance on express routes also hurts “psuedo-rapid” services carrying the express branding, by discouraging trips that only partially utilise the express sector. Typically, such routes have their express sectors divided by stops in between to expand catchment, which makes them function a tad bit more like rapids, although still very far from being one. Notable cases are 30e (rapid-stopping pattern between Haw Par Villa and HarbourFront), 97e (additional stops at NUS), 506 prior to irrationalisation (Toa Payoh sector) and 868E (intermediate stop at Jurong Town Hall). For every passenger who yields to the sunk cost fallacy and sinks the extra fare into riding only part of the express sector, many more reject the express service for the parent route, or other alternatives. Basically, it defeats the purpose of placing extra stops in the middle of the express sector in hopes of attracting more ridership through creating some sort of cyclical demand — it’s simply not going to exist with the current fare structure in place.

Taken together, the above three failings of the express fare scheme mean that express bus services almost always underperform tremendously compared to the potential demand they can serve, unless the demand across the entire express sector is strong in the first place (a la 89e and 502). Which, in an increasingly interconnective network, is an increasingly narrow niche to fulfil, to the extent even some peak-only City Directs are beginning to struggle to keep afloat. Paradoxically, the need for express services in the public transport network here hasn’t diminished however — they’re valuable as relief for congested trunk bus and rail lines whose space could be better freed up for intermediate cyclical demand patterns that are also developing in tandem with our city-state. But if the conditions to financially sustain express services are diminishing, it’s only unfortunate for those who wish for faster, or more comfortable rides, stuck in their daily sardine can commutes.

Fixing broken fares

In part, the fixed express surcharge in the present-day fare system came about because of technological limitations in fare collection — it’s easier to just impose a uniform surcharge when you have to deal with punched paper tickets and primitive farecard systems, themselves a relic of an era where bus services charged flat fares. The conditions where this arrangement even remotely makes sense today no longer exist today, with smart cashcards (EZLink) and wallets (SimplyGo) being the standard issue for fare collection on our public transport for nearly two decades and counting, with the fare collection process automated by real-time positioning that deducts (base) fares based on distance travelled.

Frankly, given how advanced our fare calculation technology is, I don’t even consider this change to our express fare structure to be anything revolutionary. But our express buses could register a great improvement in ridership overnight (without any further changes yet) simply by removing the express surcharge on the local sectors of express routes. This means that for passengers who could potentially use express routes for brief local connections, the express service is equal to other trunk and long feeder options available around him, in terms of fares, as long as he doesn’t enter the express sector. Those commuters milling about at Ang Mo Kio back then would have been able to utilise the empty 74e bus as a feeder, and that old lady needn’t be hesitant boarding an express service to travel from Chinatown to Bugis.

You can see how this will be transformative — many express services run empty in their heartland areas despite plying routes that may have high demand locally. This is an “Income Opportunity” (cue SMRT Taxis circa 2011) for express services to revitalise themselves financially, by improving their local utility as well as relieving congestion on busy local routes! Don’t underestimate the power of cyclical demand even on predominantly cumulative route profiles — the cyclical multipler easily enables buses to carry crowds many times their individual capacity, potentially without even having to pack the bus full!

Another revamp to express fares long overdue would be to transition the express surcharge to a distance-based structure too, similar to that on the basic fare structure in effect since 2010. This would make express fares “fairer” for a diverse range of potential riders who have held off using them for a wide variety of fare-related reasons, such as the sunk cost fallacy (for potential partial trips on express services), or because the express sector (and their time savings) being deemed too short to be worth the extra 60 cents.

The idea behind distance-based express surcharges is very simple — just as how your fare on basic services is determined by how far you ride them, the extra amount you pay for riding express services should be determined by how long the express sector is. To make this less abstract, distance-based express surcharges basically means that I should receive less surcharge for riding 851e, whose express sector is a mere short hop on the CTE between Ang Mo Kio and Little India, than for riding 960e, which sends me from the city to Woodlands in one shot. Instead of paying 60 cents extra for stepping on an express bus, the surcharge could perhaps be something along the lines of 5 cents per km travelled along the express sector, thus appropriately charging commuters based on distance travelled.

As significant as the change from flat to distance-based fares for basic services was in 2010, the shift towards making express surcharges distance-based too will be equally transformative. It opens up the opportunity for commuters to take advantage of lesser travel time savings from riding parts of ‘pseudo-rapid’ express services. Though not much, the few minutes shaved from removing the fare barriers to doing this will be greatly welcomed, and is the way for express services to find relevance in an increasingly connective network. There’s also a very sound economic argument for this too — as the basis for charging more on express services is the increased opportunity cost from a predominantly cumulative demand profile, it stands to reason that the extra charge should vary according to how big said opportunity cost is, which is defined by the length of the demand cycle representing how long each person occupies a spot onboard. Someone riding an express bus only partway through the express sector, who then vacates his seat for another potential paying passenger to take his place, should not pay the same fare as another passenger on the same bus riding the full route length, who thus denies his seat to other potential passengers.

I feel this might be the most controversial, so it’s been left to the last. With the first two reforms (limiting express surcharge to express sector only, implementing distance-based express surcharges) in place, it may offer us a good opportunity for a third tweak to the fare system for all buses. As much as revamping express fare structures boost the popularity of express services for a wider range of uses, the very notion of a surcharge keeps them at a disadvantage if an expressway trunk service charging basic fares only runs a nearly-identical route to the express service in question. With that in mind, a suggestion which may be incredibly controversial would be to conduct a “standardisation” of sorts for trunk bus fares, in which all trunk (long feeder included) and express services come under the same fare structure for determining surcharges on express sectors, such that commuters make travel decisions solely based on the network, rather than by service type, which would enable us to design better bus networks that focus more on connectivity and access too.

Of course, I get that a large part of why expressway trunk buses are successful is due to them charging basic fares throughout, against the 60-cent express surcharge imposed on riding express services. The additional surcharge in question can be a lot more reasonable, while still producing better outcomes for both passengers and LTA (their whining about fare revenue, that is) alike. Whatever express surcharge structure in place for a standardised fare system used by all trunk routes would definitely have to have a much gentler fare gradient than the current surcharges imposed on express services, to retain the popularity of these routes that form important links in the overall network. Maybe 2 or 3 cents per km of express sector? It seems like a loss, but the increased patronage on express and trunk routes alike following such a reform easily offsets the initial losses of reducing the surcharge on express services. On the more cynical side of things, a slight surcharge imposed on expressway trunk services is also a good first step in correcting for data biases against routes with cumulative demand (which expressway trunks fall under) in terms of fare revenue, which makes them more robust under existing KPIs of meeting fare recovery targets. Translation for those less involved in land transport affairs: it insures your expressway trunks against the possibility of future service cuts at LTA’s hands.

To sum up, the phenomena of express services disappearing from Singapore one after another is the symptom of a broken fare system with archaic origins. Despite this, their importance as key alternatives to congested rail lines hasn’t diminished one bit. It’s time we fixed the way we charge commuters for riding express buses, to keep them relevant in the eyes of policymakers, and more importantly get more people riding them, even if not for express trips.

Join the conversation here, and don’t forget to press the like button! Thanks for reading STC.

PS Many of the above-discussed examples of express routes in decline involve express routes charged standard express fares i.e. the distance-based basic fare with the fixed 60c surcharge. This excludes recreational expresses such as those for Chinatown (CT8, CT18 and CT28), Resorts World (188R and 963R) and the Zoo (926), all of which charged flat fares, and were mostly barely staying afloat even before the pandemic! This also excludes the currently operational Loyang expresses LCS1 and LCS2, which charge a flat fare higher than the highest possible adult express fare($3.20)! Nonetheless, the flat fares also contribute to their lackluster ridership, with only LCS1 bucking the trend simply due to sheer demand from Changi Airfreight Centre (which is also why 89e is the outlier in express service performance).

Leave a comment