I wish my words weren’t so prophetic, but when I wrote that the East-West Line being the sole rail connection for the entire western Singapore was a ticking time bomb in a post years ago, little would I expect those words to materialise in their literal form. Sadly, it did, and as we write, there’s no end to the mess in sight. ~amc

by averagematcha and ameowcat

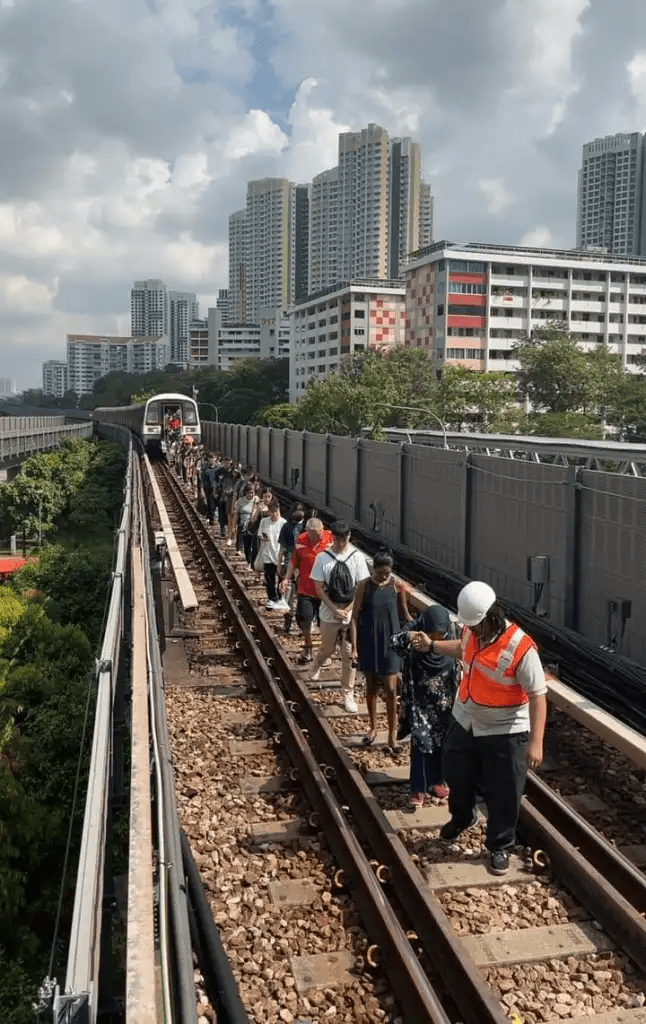

On 25th September 2024, a faulty train derailed between Clementi and Jurong East stations, knocking out power on the EWL and effectively splitting it into 2 lines for the rest of the day, with this arrangement being retained past the 26th. The unfortunate circumstance of it coinciding with the start of PSLE aside, it’s been a particularly excruciating experience for affected commuters, who may have to go without a rail connections for perhaps a few days more.

Let’s get this straight. This is truly an unfortunate accident that extends far beyond the control of SMRT, a rare freak accident perhaps, for practically no one would have expected a full-on derailment disabling the sole rail link to the west. On other days when trains break down it’d be a timely reminder of the inevitable consequences of dismantling the robust bus network we’ve built over the decades. Not today however, so you’ll hear less about disruption prevention compared to past years. However, what leaves a lot to be desired was the response to it, which still left a large corner of the country in the lurch. Overall, the implementation was subpar and many had their commutes delayed for over an hour. Here’s how the situation unfolded, what we fell short of, and what we can expect for the days to come.

Context

To summarise the chaos from the official perspective, a first-generation Kawasaki Heavy Industry C151 (henceforth referred to as KHI) train was being withdrawn after it emitted smoke from Clementi station to the nearby Ulu Pandan Depot. However, “a power trip was detected” during the withdrawal, stalling a second KHI at Clementi, and cutting the power to the tracks between Jurong East and Clementi.

Despite the provision of free bridging bus services between Boon Lay and Queenstown, the response was far from seamless. Passengers were left scrambling for bus alternatives, and though SMRT and LTA staff, as well as TransCom officers, were on-site, their presence did little to ease the inconvenience faced by frustrated commuters. Photos began circulating on snakingly long queues forming outside of MRT bus stops like Jurong East and Buona Vista, where passengers are hoping to squeeze onto the next possible Free Bridging Bus to get through the disruption. The long queues and the lack of coordination led to slow boardings, which dragged out travel time. In any case, the free bridging buses, while supposedly a direct backup to the MRT, seemed to have been much less effective as many were delayed for up to 1.5 hours. This comes a day before the first day of the PSLE Written Exams, and the fact that MOE began making contingency arrangements shows the severity of the situation. Many complained of the lack of notice of breakdown, especially at stations, and it caused confusion as to what exactly was happening. A lack of wayfinding notices left many unable to properly react to the situation.

Bridging buses to Jurong East arrived at intervals of 10 to 15 minutes, but many were packed beyond capacity, reflecting a lack of sufficient contingency planning for such incidents. To make matters worse, a downpour around 11:45 AM left passengers disembarking in the rain, compounding an already difficult situation. While full derailments aren’t the most common way to disrupt MRT services, the question then is how much longer commuters will have to tolerate disruptions caused by aging equipment and inadequate crisis management.

What changed?

Perhaps due to the protracted nature of the fallout from this derailment, some new strategies were adopted to reduce the damage that were never attempted before without prior planning. On top of the usual free bridging buses that were launched to plug the hole, SMRT also began running single-tracked shuttles for the first time in response to rail disruptions, in an attempt to partially close over the large gap that was pushing the bridging buses to their limit. From 5pm on 25th September, pairs of single-tracked shuttle trains were introduced between Boon Lay and Jurong East, as well as between Buona Vista and Queenstown, thus reducing the “dead zone” to just ground zero, the section between Dover and Jurong East. Much can be discussed on how effective this strategy is in mitigating breakdown fallout, but being the first time service patterns were adjusted on the fly, it certainly was very chaotic, with erratic services (on the mainline segment) being the norm on the 25th, and lots and lots of confused passengers.

Long ago when the TEL broke down, the need for clear and concise messaging for alternative travel arrangements was emphasised. In general this wasn’t already very well done, because this lesson is somehow barely learnt despite the numerous frustration from repeated disruptions. Here’s the thing. When train service patterns change on the fly to close the gap, the need for clear communication becomes even more important! While walking the ground on the 25th shortly after these extra shuttle trains were launched in the afternoon, chaos erupted on the shuttle section between Queenstown and Buona Vista, as confused passengers were sent on back-and-forth relays trying to figure out the new operating arrangements on the spot. It also didn’t help that trains from different service patterns were turning back using the same platform (in the case of Queenstown, although I expected a similar situation to pan out at Boon Lay too). That by the way also made things slightly messier due to the huge crowds making conflicting movements on the train platform, although this is what happens when you simply have such high passenger exchange forced by the hand of trains being short-turned.

Something that LTA and SMRT (SBST as well, even if their trains don’t screw up as often) need to be acutely aware of, especially when trying to communicate spatial information to the public quickly: Not everyone is a train or bus otaku, to whom the complexities of these convoluted bridging service patterns immediately make sense. Perhaps I as a train enthusiast with knowledge of the track diagrams can visualise the train movements with some pattern recognition, but most members of the public would start panicking in confusion when they see trains driving the “wrong way” on the viaduct, which I encountered quite a lot while passing through the shuttle sectors. One important axiom of information design: assume the other party is an idiot. In times of crisis where people are not in their clearest states of mind, it may be useful to risk offending some passengers’ intellect, rather than muddle the waters further with ineffective communication.

We’ve mentioned this before: Various screens available on our public transport network, such as the STARIS/DRMD inside trains or the PIDS inside buses, or even the new digital bus arrival boards at bus stops, should be made use of fully to communicate real-time updates to the public effectively, because a bunch of posters in unassuming corners of the station isn’t cutting it. Sometime earlier this year this feature got added to the bus stop boards, kudos to LTA for putting in the effort, although I really wished the message was a lot more prominent, rather than having it squeezed in bottommost row, out of the line of sight of basically everybody.

Heck, an interesting observation is that disruption updates, in the context of this derailment, are also being posted on the Straits Times and similar news outlets in real time. That being said, it remains to be seen if such guerrilla messaging tactics will be employed for less serious, but no less disruptive train breakdowns in future. Another failure of information design in crisis management is navigation for alternative routes. Sure, a banner listing down what buses you can take to every other station on the MRT network exists at every station. But that’s not useful information, because it tells you nothing about how long it takes to get one there (3 hours from Jurong East to Hougang by bus 51, anyone?), and neither does it show you how you could connect to other bus or rail routes to get to your destination faster. One such banner at Redhill MRT might tell you to take bus 145 on a windy route to Toa Payoh (nearly 2h), while the far faster bus-only option (taking 132 to Stevens, and then transferring to 105 or 153) would get you there in half the time, if only the information was presented from a network perspective, rather than a point-to-point perspective. Numerous people have made similar parallel bus connections maps for this disruption and numerous more before it, and it’s a call for LTA to do the same eventually. It’s too late to call that in for this derailment incident, although we definitely should be preparing for the next major rail breakdown even before the one in front of us concludes.

Unused resources

And while the saga was happening, a very critical system was running under the guise as an “emergency backup”, which was never fully maximised to its full potential. They are our trunk bus network.

When it comes to MRT disruptions, the option everyone looks to for a direct alternative is none other than our existing bus network, and the Free Bridging Buses. However, the application of buses as a backup to EWL is strongly misguided.

Buses should not merely serve as a backup or “feeder” to the MRT system. They must be positioned as an equally viable and reliable option for commuters at all times. The lack of bus prioritisation perpetuates the perception that buses are slow (bus priority needs to be further improved!) and should only be used for last-mile connections, diminishing their full potential. This has proven to be true with the ludicrous travelling times incurred yesterday due to the disruption, with some commutes going past 3 hours. For example, in off-peak hours, a journey from Clementi to Jurong East can take 25 minutes, and 20 minutes from Buona Vista to Dover.

This is attributed to the very fact that there is an alarming lack of bus priority on the roads. Buses get slowed down by insanely long traffic cycles and slow-moving car traffic, preventing buses from fully utilising the sometimes-provided bus lane. The situation gets worse when it was the peak hour rush, as you have many Free Bridging Buses and trunk buses sharing the same road with a large pool of cars. Talk about car-lite! Unfortunately, this does not just exist within the south-western region where the disruption affected. It is everywhere. The lack of bus priority delays buses from warping from station to station, which paints this ungodly picture of a slow, delayed alternative home.

On FBBs, and why they’re not

It’s time to talk about the entire concept of free bridging buses (FBBs) again, and why they’re not an appropriate relief for disabled rail line. Being the most important rail link for western Singapore, the EWL disabling itself resulted in a very large crowd displaced. And things got really, really ugly for the many trunk buses that remotely served a connection along the disrupted sector of EWL. Because there’s just so many agonising examples taken from many locations and across various times of the day, here’s a dedicated gallery to all of them:

You may notice a common theme among many of these screenshots. Why are there huge, gaping frequency holes in all these critical trunk (and even, gosh, express) services, left and right, all shockingly packed beyond capacity? Particularly in the case of 198, which closely duplicates almost the entirety of the deleted EWL sector between Boon Lay and Queenstown (198 serves Boon Lay, Jurong East, Buona Vista and Commonwealth stations), wherefore these ungodly gaps?

Remember how FBBs work: Buses, and bus captains driving them, are removed from the existing bus system in order to drive a new “route” established to link only to the affected train station. While some of the resources come from spares available on the bus operator’s hand, the overwhelming majority of these are poached from existing routes! One can only imagine how crush loaded the trunk routes paralleling EWL, which already enjoy very strong demand due to the EWL’s network insufficiency, have been the past two days!

This leads to an extreme form of the conditions in which bus bunching arises, where the incredibly long dwell times at every stop due to high crush loading (passengers must shove themselves on and off the bus at every stop), coupled with LTA’s dogmatic refusal to use more efficient bendy buses in our fleet, result in bunching occurring, even at greatly reduced frequencies where such scenarios usually do not occur! What happens? Horrible holes 20 to 30 minutes wide during the peak hours on the very trunk routes intended to scoop up the mess caused by the train derailment!

The BCEP and the practice of operating FBBs during a train disruption share one thing in common: both commit the act of spreading resources even thinner, by having the same fleet operate on a larger spread of routes! When a sudden surge in demand for routes in the bus network occurs, the last thing that should happen is further spreading thin operating resources, and thus weakening the ability of the bus network to carry the burgeoning crowds to their destinations! In my previous post on the TEL disruptions in their early days I highlighted possible alternative existing routes as options to bolster in the event of a disruption. A bit too many, some may have felt, for such a short rail segment. Well, for the EWL segment that is still down as we write, the candidates for strengthening are far more clear-cut. 99, 185 and 198 are exceptional candidates in linking Jurong West to Jurong East, Clementi and even Buona Vista further down.

Rather than trashing trunk services for FBBs that cannot effectively clear the crowd, it would be a far wiser option to distribute the large passenger crowd among the larger number of trunk routes available that also connect to other destinations not directly along the EWL. Think about it: even a dedicated shuttle bus arriving every 3-4 minutes is unable to compete with even half a dozen routes each running 10-15 minute intervals each! Rather than further disperse operating resources, the correct action to take is instead to strengthen the trunk bus network during a disruption! Instead of punching large, 20-minute holes in the buses that actually bring people where they want to go, what little additional spare resources on hand should go towards boosting the real parallel routes that actually link the affected MRT stations to passengers’ destinations. For instance, 99 and 198, the two routes observed to be most affected due to their largely parallel routes to the EWL between Boon Lay and Commonwealth, should have been pumped to run 8-10 minute frequencies, ideally with fleet swaps to run full double-decker fleets over the course of this week-long shutdown on the EWL.

What is even more irritating about the FBB arrangements was how trunk routes beyond the vicinity were ransacked of their high-capacity fleets to provide a lackluster and underperforming shuttle service that was just a much slower version of the MRT (by a factor of 5, based on the experiences of Straits Times’ reporters who timed the routes). Trunk services from all across Singapore, such as 74 (which plays critical peacetime CCL relief roles), 89 (the sole link to Loyang from the northeast) and even 25 (the main constituent of service along the medium capacity corridor from Ang Mo Kio to Eunos), experienced great service reductions just to provide additional double-deck buses for the ineffective FBB services on the other side of Singapore. What is even more irritating was what was not ransacked for the FBBs — inefficient, monocentric feeder services with no demand continued to hog large numbers of high-capacity buses, bunched together and running empty, instead of being redeployed to trunk services paralleling the EWL that actually needed additional help.

A double failure is reflected here — both of the Bus Contracting Model and the hub-and-spoke ideology that LTA views public transport under. As observed, the failure to redeploy high-capacity buses from wasteful feeders nearby to either FBBs or regular parallel trunk buses occurred because both sides of the imbalance were on different sides of BCM boundaries. The EWL FBB services, under BCM, are assigned to SBS Transit and Tower Transit, conveniently leaving out SMRT, who has been operating the Jurong West package since the start of the month. High-capacity buses squandered on wasteful and inefficient Boon Lay feeders such as 240 and 243G/W are unable to be redistributed to areas where these buses are more needed, as SMRT’s Jurong West obligations somehow do not include picking up the slack, even in a train disruption affecting Boon Lay. All because of a bunch of bureaucratic walls put up, even where they don’t make sense. Oh, and the trunk routes that have been hard carrying demand across the gap since 25 Sept are not under SMRT, so more hurdles!

The approach of cutting at trunk routes while keeping empty feeders running at high frequencies is the pinnacle of hub-and-spoke ideology in action. In more layman terms as someone from the Discord server puts it:

LTA: buses have 2 (two) uses: feed to trains, and act as trains when they break down.

I don’t need to go into the absurdities of such an approach, and this incident has definitely made many west side residents very averse to hub-and-spoke arrangements, or the rail-centric mindset that LTA has been propagating. It’s come back to slap them hard in the face, and perhaps for the better, if it means more prioritisation of a robust trunk bus network in the west going forward, under BCEP or anything else.

Contrary to the Hub-and-Spoke model, the bus network isn’t just for filling gaps; trunk bus routes offer comprehensive coverage that could serve as a real alternative to rail, even when the trains are running smoothly. Unfortunately, the LTA and SMRT have failed to effectively promote these existing bus services, which already connect key stations and areas. (To be fair they tried, but the messaging was horribly ineffective) Instead, commuters are pushed to inefficient FBBs and “alternative” rail routes taking a long detour around half the country. In conclusion, FBBs are counterproductive to crowd management, and future rail disruptions will do well with the practice abolished, instead focusing on boosting existing trunk routes, and only introducing specialised temporary shuttles for stations which genuinely do not have trunk bus connections otherwise, which are a great rarity in the MRT network.

This ties back into the previous point on messaging of alternative routes. FBBs become necessary in a disruption (even though they’re not, and do more damage than they help) because of entrenched travel patterns, both in the heads of commuters and LTA planners’ modelling, that focus exclusively on the rail network as the sole means of long distance travel. Hence, the need for FBBs is inflated because many are unaware of alternative travel options that are not direct parallels of affected rail lines. Messaging from LTA and SMRT further reinforces this rail-centric mentality. The officially-recognised alternative routes (until late on the 26th, when SMRT added more regular trunk routes to the list of suggested alternatives) for quite a while was either to wait for a FBB…

or detour through the rail network via Woodlands to get from the city to the west!

Look at those insane FBB queues again. Many queued for the FBBs only at the bus stops outside affected MRT stations, mostly out of a lack of awareness of possible alternative trunk routes which they could have boarded, and skipped the long wait. Remember, the regular trunk network has more combined capacity than even the most frequent FBB service! In the case of the Buona Vista westbound FBB stop (the one pictured by Mothership, outside the MOE headquarters building), a bit more awareness would have told many of these people to consider taking 74 to Dover (or 105 and 106 from Commonwealth Ave West), or 198 to Jurong East. Towards Clementi, cross the road and catch a westbound bus on 14. And what if they didn’t even have to get held up at Buona Vista in the first place? What if more CDS trips were deployed ad-hoc on disruption days, so that office workers in the city would directly bypass the disabled sectors of rail lines and get home quickly?

Alternative route messaging should focus on showing where people can go, by displaying the network of routes around them which they can rely on, thus answering the question of how they can get there. This, instead of prescribing options based on direct connections, which may not be desired by affected commuters themselves!

The rail and bus systems should be integrated as co-equals, not pitted against each other in a hierarchy. Proposing convoluted rail detours (via Woodlands) highlights both the lack of public transit literacy in Singapore and the misplaced perception that buses are INFERIOR. Ironically, when buses are pulled from already overburdened trunk routes for free bridging services, they undermine the VERY system that could have solved the problem. Instead, ramping up the frequency of existing trunk bus routes would provide a seamless alternative to the MRT, eliminating the need for an additional transfer while delivering commuters directly to their destinations.

If this isn’t a better solution, what is?

Postscript, and a note on transparency and accountability

Note the way official media have been covering this incident since it began on the morning of the 25th. A long mash of words that helpfully inform us of the fate that befell the individual components on the faulty train that day. SMRT’s top two figures, their CEO and chairman, also issued a joint statement around 4.30pm on the 25th, going into intricate detail of the technical aspects of the fault.

UPDATE on the power fault on the East-West Line at 4.28pm:

“We would like to express our deepest apologies to all our commuters for the significant disruption caused by the power trip. The incident was the result of an unforeseen issue during the withdrawal of an old train, where a defective train axle box on one of our first-generation trains dropped and caused the wheels of a bogie to come off the running rail and hit track equipment, including the third rail and point machines, leading to the power fault.

At SMRT, we hold the safety and well-being of our commuters and our staff as our highest priority. We fully understand the inconvenience, frustration, and delays this disruption has caused, and we deeply regret the impact it has had on your journey. We are working relentlessly to restore service quickly.

Once again, we extend our sincerest apologies for the disruption and deeply appreciate your patience, understanding, and continued trust in SMRT.”

— Seah Moon Ming, Chairman, and Ngien Hoon Ping, GCEO, SMRT Corporation

But at this point I want you to take a step back and look at the situation on the ground again. Brush aside all the jargon about dislodged axle boxes and faulty bogies, what is the big picture here?

See the train cars misaligned on the track? What does this mean, in layman terms? (Or, what word did we use to describe the incident on the 25th?)

The train had derailed.

Yet, it appears as if every effort was undertaken to avoid saying the word “derailment”, as if some top officials were deathly afraid of the public knowing what had transpired on that secluded track segment between Clementi and Jurong East. As of publication time, more than 50 hours had elapsed since the train derailment, but SMRT has yet to officially acknowledge the derailment explicitly. Just like how the 2017 Joo Koon crash was initially euphemistically termed “trains coming into contact” before the large numbers of cameras on site forced SMRT to come to terms with reality and admit the crash within the same day. This time round, perhaps because the derailment site was hidden behind large bushes from the not-so-well trafficked road next to it, news of the derailment did not spread as quickly (but it still did), probably lulling SMRT into believing they can get away concealing the gravity of the situation.

Unfortunately, heaven is always watching, and anyone who isn’t blind can clearly see a derailment. For the top two executives of SMRT to write an entire copypasta-level essay just to avoid saying the word “derailment”, demonstrates a horrible lack of accountability for the incident, and a refusal to admit failure, even when the emperor’s new clothes are out to see for everyone already. Even the news, who has access to images of derailed rolling stock much clearer than any amateur photographer standing from a carpark far away can capture, has shockingly been compliant and has refused to call it a derailment for what it is.

The Straits Times eventually released a piece on the 26th admitting that a bogie derailed (note: no mention of the train!), 31 hours after the derailment took place. Finally, 38 hours after the faulty KHI train derailed outside Ulu Pandan depot, the first acknowledgement of a derailment came — by a foreign source, SCMP. Time check as of 1.30pm on 27th September 2024, when this post was published: 52 hours since the derailment. Still no acknowledgement of a derailment officially! Why? What is there to hide when everyone is affected, and is feeling the pinch from the closures caused by the derailment?

How hard is it to admit that a train derailed, and that it would complicate recovery efforts much more, rather than overpromising recovery dates only to be unable to meet them? Which, by the way, had happened twice as of posting time: a recovery by the 26th was targeted on the 25th, and another targeted recovery for the 27th was made on the 26th, both of which never materialised, leaving the final targeted recovery date of 30th September, which remains to be seen whether it will be fulfilled even. In fact, officially acknowledging the derailment as early as possible would have helped ease the pressure a bit, as saying the word derailment instantly carries the severity of one! Everyone is agitated that Western Singapore is isolated from the rest of the country for a week, but perhaps it would be tempered with a bit more understanding, and a lot fewer angry demands on social media to forcefully reopen the severely-damaged line earlier. If only it was communicated clearly to everyone that it was a derailment, rather than the “20-minute delay” or “power fault”, the excuse which SMRT ran on for the entire day on the 25th and 26th.

But no. SMRT chose to keep mum about the derailment, and even went the other way, covering up (pun not intended) the EWL section of the disruption alert screens at MRT stations with masking tape to prevent commuters from seeing the real status of the line! Irresponsible is an understatement.

With this disruption expected to last for six days in a row, its impact and severity far outstrips even the 2011 twin breakdowns. I’d be ashamed of myself for saying we did this better than 13 years ago. The callous lack of accountability on SMRT’s part to acknowledge the nature of the disruption, coupled with routinely inadequate contingency measures, brews a bitter pill that all westies have to inevitably swallow until… honestly, I don’t know. I have a feeling the EWL won’t even be able to resume service past 30th September, given how deep-seated the damage to the infrastructure is. Jiayous, and hold out in there while you can, and learn more about the many trunk bus routes in your area that are your best friends in the meantime.

This derailment has exposed the structural flaw of our public transport network — the western half of the country’s overreliance on the EWL as the only viable means of getting around anywhere quickly. May this be a case for advocating improvements to the bus system such that they have more viable and realistic alternatives to the EWL, with the added benefit of a more efficient bus system as a result of it being faster. It’s also a convincing case for wanting a second rail line serving the west proper to be built, although those are matters best left for a general-purpose post discussing connectivity in the west.

For now, LTA must prioritise two things while the rails get replaced and repaired: robust trunk bus networks, and higher-intensity City Direct services! Today’s not the day to yap about bureaucratic boundaries under BCM. Buses need to be spammed (not on FBBs), and these boundaries should make way for pressing travel needs of affected commuters. To hell with red tape!

Join the conversation here, and don’t forget to press the like button! Thanks for reading STC.

Leave a comment